10th August, 2013. It’s a hot day in Siberia and we’re waiting outside the Ivolginsky Datsan Buddhist Temple, just outside Ulan-Ude – the final stop on our Mazda Route3 adventure. “You’ll present this to the Lama” starts our guide, as she passes us a scarf to drape over our arms. “He’ll accept your gift. Take it back and step away from him without turning your back, it’s disrespectful to turn your back on the Lama”. Okay. Our time comes to enter the temple, and we do as our guide says; we walk up, one by one, bow, present the gift and… wait a minute, the Lama’s in a glass box and… he’s… he’s dead. If we’d learnt anything after four days in Siberia, it was to expect the unexpected. But a dead guy, in a glass box? Forgive us for momentary shock.

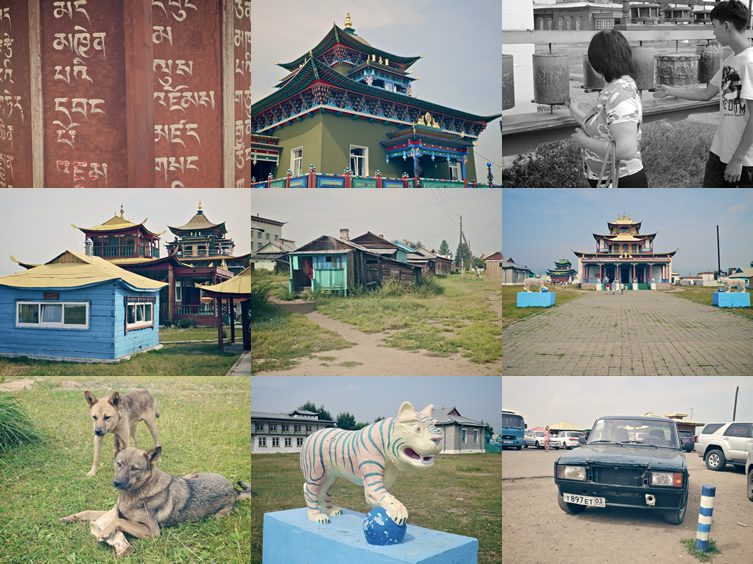

Turns out Dashi-Dorzho Itigilov, born 1852, has been with the great monks in the sky for some 86 years. Leaving wishes to be buried in the Lotus Position and exhumed years later, his fellow monks duly obliged, examining his remains in both 1955 and ’73. What they found was nothing short of a miracle and, fearful of the Soviet Union’s reaction, kept Dashi-Dorzho Itigilov under wraps – literally – until 2002, when an official examination revealed a mystifying lack of natural decay. The Lama’s disconcerting body now greets fellow monks, pilgrims, visiting dignitaries and unsuspecting travellers at the peculiar Buddhist theme park that circles the temple. Part tourist attraction, part market, part place of worship, the surroundings of Ivolginsky Datsan (considered to be Russia’s epicentre of Buddhism) are as typically contrary as most religious sites, fascinating nonetheless.

Regardless of its scientific phenomenon, a Buddhist monastery in Russia is seemingly an anomaly in itself but, this close to Mongolia, there’s a lesser sense of being in Russia. In fact, throughout our trip, there’s been a definite sense of being in Siberia rather than Russia per se – but then, a country that spans half the globe, from Scandinavia to Alaska, Latvia to China… it must be hard for one solitary government to impress its personality upon such a vast land mass. And what defines Siberia? It is in itself a leviathan of almost incomprehensible size; 13.1 million square kilometres, practically all of North Asia. Its governance may be increasingly fragile too, by all accounts there’s an increasing interest from China, 90 million inhabitants on their side of the China/Russia border, just six on the Russian – one to keep an eye on with China’s growing international dominance. Here, in Ulan-Ude, the city’s proximity to Mongolia can certainly be felt – advertisements around the city show Asian faces, and the city stands at the point where the Trans-Siberian Railway connects to its Trans-Mongolian counterpart.

That said, Soviet-era Russia still looms dominant over the city – built in 1970, the centennial of Vladimir Lenin’s birth, Ulan-Ude’s main square is looked over by a 25ft statue of the communist revolutionary’s head. A perverse reminder of days when Moscow ruled with an iron fist. It’s Russian history of a different kind that dominates our afternoon, a scenic drive up the Selenga River – that flows into the world’s deepest lake, Lake Baikal, home to 20% of our planet’s entire unfrozen freshwater reserve – to the village of Desyatnikovo, the site of a 250 year-old “Old Believers” settlement. We get food (decidedly edible, at last), entertainment (enjoyable, bar for one unfortunate member of Team We Heart) and a fascinating insight into history and traditions. The long days of driving are over, the mood of the group has shifted. The sun is shining and Siberia is looking after us, whisper it: we might actually miss this insane corner of the wild, wild east.

A good day is rounded off by a good meal, Mongolian cuisine is vastly superior to the Siberian stodge we’ve encountered over the last few days, and our final meal reaches its own finale with local musicians and a communal dance off. Back at our hotel we find ourselves amidst a local wedding, vodka (and plenty of it) is forced upon us (OK, force may be a tad strong a word). Little sleep is followed by an early morning as we head to the airport for our return to civilisation. Much like its roads, Siberia is an unpredictable beast. It is vast, unrelenting, often torturous (and tortuous), but ultimately thoroughly engrossing. As we pass the eighth new Mazda3 to roll off its Hiroshima production line onto new drivers, it’s with heavy hearts. The Mazda is a plucky little fella and has navigated difficult roads with considerable ease, sucking up all that the far east of Russia has thrown at it. We’ll miss it, and, oddly, we’ll miss Siberia too. ‘Once in a lifetime’ is a terrible cliché but, for once in a lifetime, it’s awfully apt.

***

Photography © We Heart