Described by Thomas Edison as ‘the eighth wonder of the world’, Linotype machines revolutionised the way we printed in multitude; invented by German born American immigrant Ottmar Mergenthaler in the late 19th century, the overwhelmingly complex contraptions allowed for mass type-setting, ergo mass printing. To create sentences or ‘slugs’, the operator would command letters using a typewriter-style keyboard that would then be cast using molten metal and the slugs would be placed in order before being sent to print. In a nutshell. The feature length documentary, Linotype: The Film, divulges much more, telling the charming story of the people connected to the machine from its early days through its saddening demise.

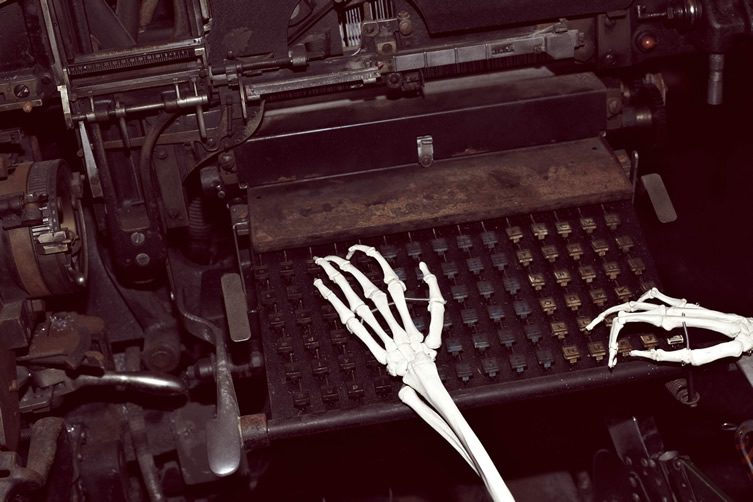

It’s a mild autumn night, and We Heart are sitting through said documentary, having been invited to attend Urban Cottage Industries and Print Club London‘s one-off fiesta of the Linotype machine at MC Motors in Dalston. Purveyors of vintage lighting and print supplies, Urban Cottage Industries rescued several from the scrap yard back in 2011 and, having already established a relationship with Kate Higginson, Print Club London’s Director, they decided to “share a commitment to engaging, original and authentic print”. During the event, the wondrous machines were not just on display but in full operational order. ‘Clink clink swish clink’ could be heard all evening. Eager fans and curious folk gathered around to catch a glimpse of the beasts in action and try their hand at Linotype’s smaller forefather; the letterpress.

I spoke to Stan Wilson and Sophie Gollop from Urban Cottage Industries, along with Doug Wilson – Linotype: The Film‘s director and producer – about the importance of passing on the Linotype legacy…

How important really was the Linotype machine?

DW: The Linotype was as important as the internet is today. I like to call the Linotype the “Twitter of 1886” – it brought news from week-old news to hour-old news – which was a huge shift in communication and journalism.

ST & SG: The history of print, like history generally, is contested. You could subscribe to the ‘great men’ theory of history: rapid change in printing was the result of individual genius. Or alternatively: gradual technological, social and economic change builds to the point where rapid change is inevitable. The focus for improvements in printing, like any technology, is one of the most costly parts of the process. Type was being set by hand in the late 1800s much as it had been set in the mid-1400s. People had been seriously trying to crack the problem of slow manual typesetting for at least 100 years before 1880.

The Linotype machine solved it and made it much cheaper to produce printed material. The increase in printed material drove literacy, which fed back in demand for more printed material. Linotype is in anyone’s top 10 revolutionary printing technologies. But looking back, there is an air of inevitability about fast mechanical typesetting – like a machine which sews, it was too good an idea for us humans not to realise.

Photo © We Heart

How many ‘ready for scrap’ machines do you think there are across the globe?

DW: We don’t have any solid numbers, but the best guess is that about 120,000 Linotype machines were manufactured. Almost all of them were scrapped, but there are likely less than 1,000 machines left in the world and only 100 that are still in working order today.

ST & SG: Impossible to say, but it seems there are lots of rusted solid machines about, and very few operational ones. They were rendered obsolete in the 15 year period between 1970 and 1985. Typesetting was usually located on the top floor of a building because of the natural light. When the end came, Linotype machines were pushed out of the upper floors of buildings to their destruction and the broken carcasses picked over for scrap. We needed a particular machine earlier this year and were about to send our expert to the USA; but one turned up in Wales at the last minute and we snapped it up.

Why should we celebrate and/or help to preserve the past? How important is the Linotype legacy?

DW: Without the advancements in communication that the Linotype brought along we would not have the 24-hour news and information that we have today. I believe it’s important to celebrate and preserve the past because it allows us to appreciate the current technologies and look towards the future.

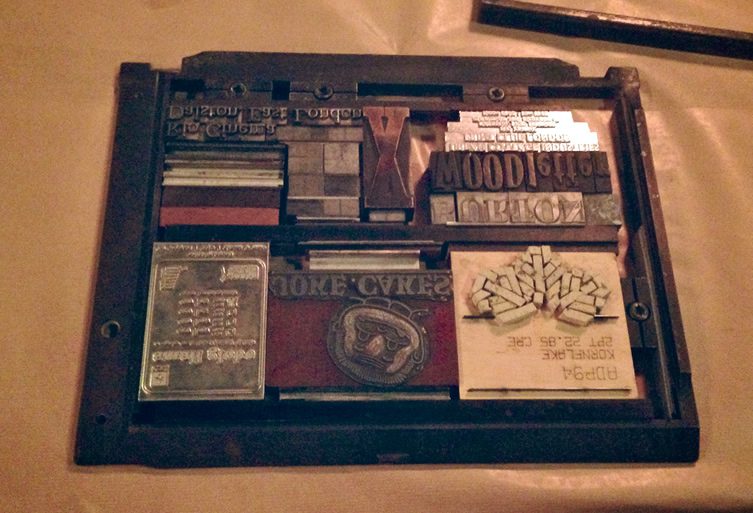

ST & SG: We’ve no ethical or ideological commitment to the past: we want progress and we embrace modernity when it comes to, say, social values, health care and plumbing. However, Linotype machines are not only a part of human history, they also produce beautiful typography and that’s why we run them. They’re not great when it comes to practicality; but when it comes to beauty, hot-metal type has much more to offer than digital print.

Photo © We Heart

Have you used the machine yourself? How difficult is it to operate?

DW: Yes, I’ve used the machine on several occasions. I only know how to use the Linotype if everything is working perfectly – if something stops working, I have no idea how to fix it. It is easy to operate if everything is working fine, but VERY complicated to fix if something goes wrong.

ST & SG: Linotype machines are easy to operate in terms of pressing the keys – it’s much like a typewriter. But there’s lots going on behind the keys: keeping the machines running when they were new was a skilled job; it’s a highly skilled job now they are ‘getting on a bit’ (the machines not the operators).

—

Urban Cottage Industries along with Print Club London are now working in conjunction to put the rescued machines into use. Having spent almost two years rehabilitating these amazing feats of engineering, they’re beginning with personalising books and small greeting cards. Here’s hoping that the future of the Linotype machine is not over just yet and that in years to come we continue to appreciate beautifully set type the traditional way.

@PrintClubLondon

@urbancottageind

@linotypefilm

***

Photo © We Heart