James Jarvis graduated from the Royal College of Art in 1995. He has since embarked on a busy career creating numerous characters and fantasy worlds for commercial advertising and magazine editorials.

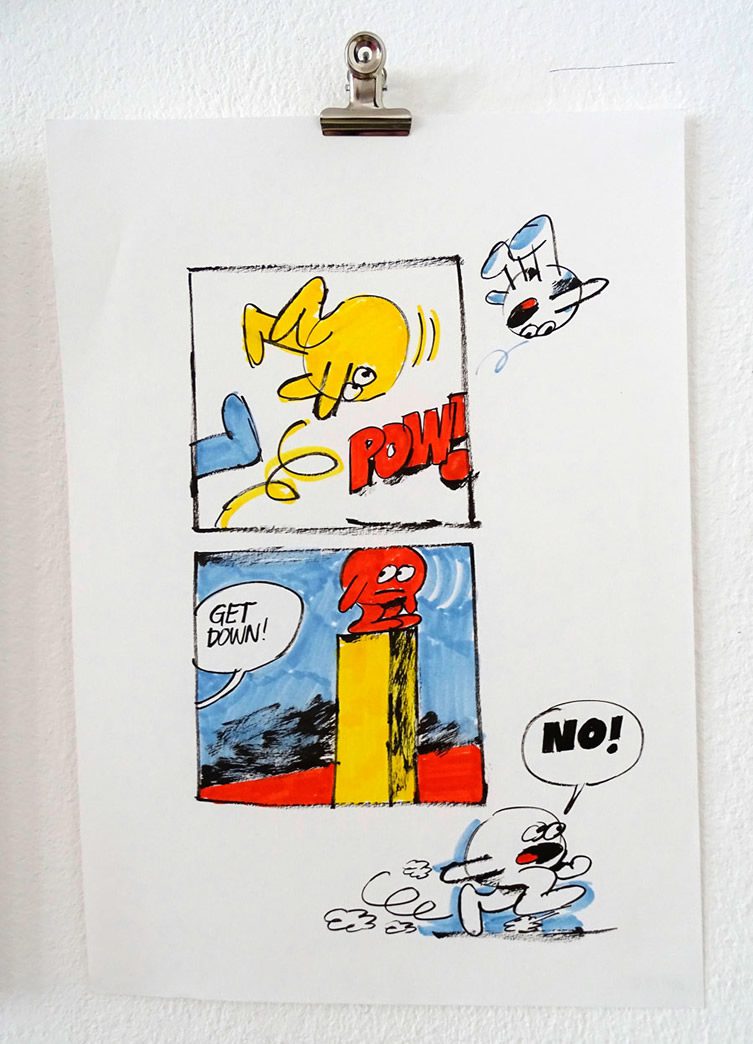

Jarvis is perhaps best known for his plastic creations, which have helped shape the nascent world of designer toys and collectible figures. He is responsible for a large cast of almost 100 characters, now forever immortalised in plastic. Having previously designed figures for others Jarvis co-founded AMOS Novelties Ltd. which, up until 2012, was the exclusive base for all of his toy figure work.

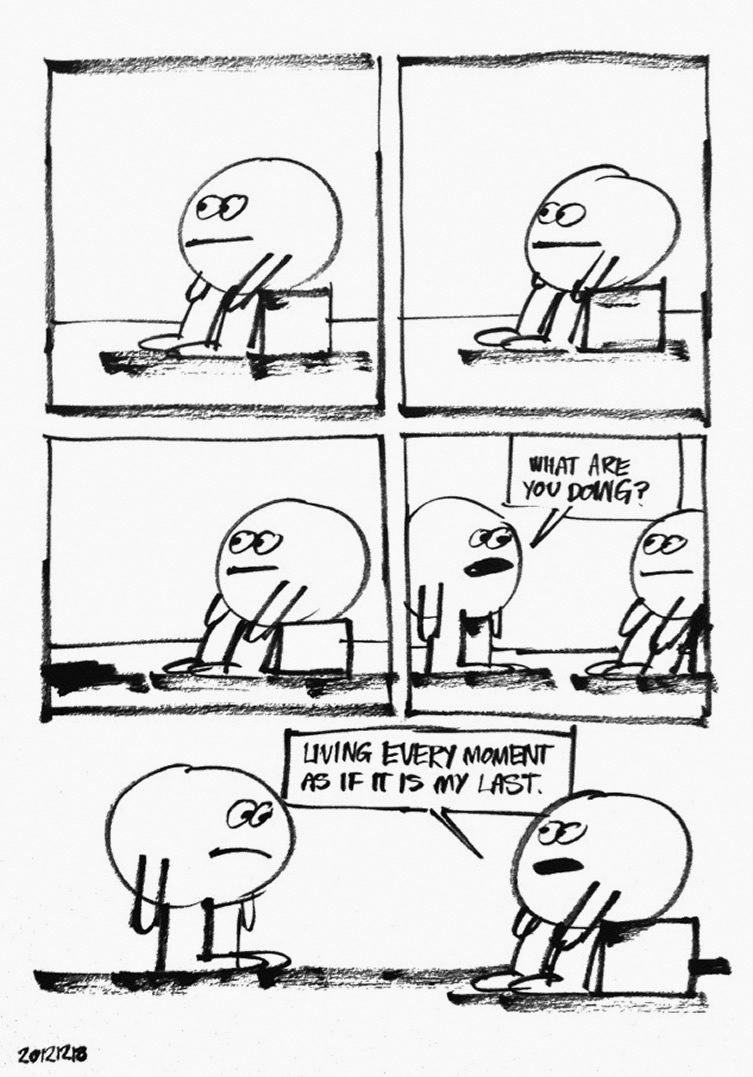

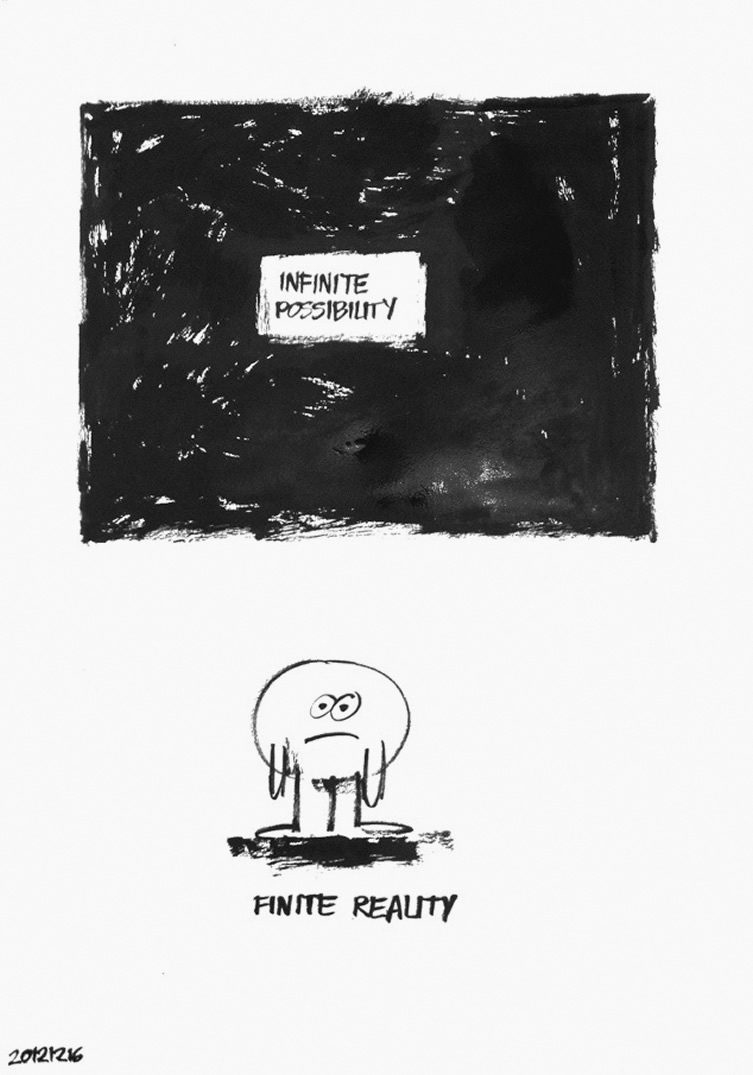

Recently he has been exploring philosophy, architecture and conceptual art through an on going series of cartoon strips titled Spheric Dialogues sharing his drawings daily on Instagram and a dedicated blog. In a continuation of these themes, his Pictoplasma exhibition Classical Allusions displays a collection of drawings featuring an archetypal spherical character, referencing classical works of art.

Can you tell me about the role of drawing in your work and the ideas you’re exploring now?

Drawing is just what I do. The drawing is the raw intellectual material. It’s a fundamental aspect of what I do and the kind of work I like to show the most.

How has your visual style evolved? What are your thoughts on style?

I was taught by a generation of illustrators and artists who saw style as maybe more of an intellectual thing. George Hardie [he drew the cover to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon] was one of my teachers. His work is all about thinking about something and choosing a visual style that’s suitable for solving a particular problem, whereas now the focus is for students to find a definable visual style which you use to sell yourself, rather than an intellectual one, and this is something I struggle with and react against, and yet, I’m probably part of a generation of artist illustrators who are responsible for that maybe happening.

How do you balance commercial work and personal projects?

I try and make my commercial work personal and my personal work commercial, and then there’s less of a contrast. I think with commercial jobs like, I try not to just lend my visual style to a project so I’m not just illustrating someone else’s concept. I try and make it something that I would do. I’m lucky that I don’t do a lot of commercial jobs a year; the ones I do tend to be big enough that they’re familiar with my work and know why they’re using me. They understand that if you ask me to illustrate something you’re not necessarily going to get the best from me whereas if you ask me to conceptualise something and really think about the project I’m then driving it creatively.

How did this lead on to vinyl toys and developing your character design work?

Pure accident. It was back in 1997, my friends ran a clothing label called Holmes, which came out of Slam City Skates. I was just drawing characters for t-shirts and catalogues, and their distributor in Japan suggested we make a toy. So we did, just because we could. The toy ended up being made by Silas in 1998. People liked them so we continued to put the toys out and eventually we realised that the toys didn’t need to be associated with a clothing brand, so AMOS was created to make the stuff I designed. There was never a plan.

How do you feel about being labelled as a character designer?

I’m a bit ambivalent about it. The danger is by setting out to become a ‘character designer’ you end up limiting what you do; my motto is ideas come first then you can apply the most appropriate style to the outcome. The reason we stopped doing toys, and stopped AMOS, was because we felt we had done all we could do with toys as the medium. I felt like there were other things I wanted to say. We felt if we stopped after 10 years it would be this great project that we could be proud of, rather than carrying on and diluting it. So I made the decision to stop making toys and moved on to make my book on philosophy and other projects.

For many people I’m known as the guy who makes toys, so it might seem like the work I do now is radically different, but drawing has always been my main interest. When I was a kid was just drew stuff, and all through AMOS I was drawing stuff, so it’s less full circle, more that I have come back from a diversion. A lot of the toys we made were about pop culture and I didn’t want to just create work about that.

Talk to us about your latest collection of drawings – it features a spherical character drawn in brush pen, a stark contrast to your earlier ‘vector’ characters. How did he come into being?

I didn’t set out to be a ‘character artist’ I was just drawing comics and cartoons – I didn’t want to draw people or animals, I wanted them to be their own kind of thing, so I ended up growing these potato shaped heads that I ended up making these toys out of them.

The reason I stopped drawing the potato heads was for several reasons; firstly because I didn’t want it to be the only thing I ever did, there was also things like this growing interest in conceptual art and gestures and movement. I realised my drawing wasn’t an intuitive, instinctive process; drawing the potato heads felt restrictive in a way. So I started making the spherical character as a reaction against that, but at the same time I was watching my kids draw and they always started with a circle, two eyes and a mouth. There’s something so elemental about creating a basic character to express intellectual ideas, especially when you compare it to the wealth of overly decorated characters out there. Personally I’m against decoration, and when I catch myself decorating I know it’s wrong. There’s a saying: decoration is a crime. I agree with that.

Has it been a challenge to step away from the work you’ve best known for and pursue this new direction with drawing?

I find it really inspiring that you can reinvent your practice at any stage in your career, I like artists that have a craft in what they do and they just get better and better over time. I just felt that for me, the craft is in the intellectual material not in the execution, in how pretty my pictures look. Making the decision to be like that enabled me to pursue another path. It’s liberating. It’s easier for me to say things through drawing, as opposed to working with vectors, though I still work like this commercially. When I first started drawing this character it was just to try something new, something which I created instinctively. I keep having these points in my career when I want to re-boot like I kind of want to be ‘James Jarvis 2.0’ but because people buy into your work at different stages you don’t want to reject the earlier version of yourself.

Sometimes I feel like I would like to make abstract art, but I think that there’s an accessibility to work with characters in it – it opens it up to people – that’s the power of having a cartoon character, that it can help explain ideas.

How important are events like Pictoplasma to you as an artist?

It’s important because otherwise I wouldn’t talk to anybody! I work from home now, take the kids to school, sit at my desk at work and then I do stuff with the kids. So I don’t go out that much. I’m quite interested in thinking about what I do. But when you venture out it adds another layer of discussion. Meeting other artists gives you the opportunity to debate issues, discuss your artwork, ask questions… it gives you perspective.

***