In a studio near London’s Brunswick Centre, Richard Rhys, founder of Pattern Foundry, is re-imagining not just the way we use tiles, but how we can incorporate patterns into our lives.

Since 2005 Pattern Foundry has been steadily, and quietly, commissioning patterns from an impressive range of names; from some of the most well-respected figures in contemporary art and graphic design, to individuals from the world of music and mathematics. With around 400 patterns in the archive, and more to come, Rhys is re-thinking the pattern as a new way of interpreting and translating the work of leading thinkers and image makers. Rhys has also used the archive to create sets of ceramic tiles that feature elements from the original patterns, which can be freely arranged to create new and unexpected editions of the original design.

Intrigued by the idea of presenting an individual’s thought process and work through a pattern, Rhys was drawn to the idea of commissioning work from people across various disciplines, including those outside the traditional creative industries. “The process of working with people who don’t necessarily come from a background where they can visualise their ideas is really fascinating,” explains Rhys. “It means I can work with just about anyone to make a pattern.” Aside from leading figures from the world of design like Karel Martens and Wim Crouwel, Rhys has also worked with the likes of mathematician Marcus du Sautoy and German techno artist Thomas Brinkmann.

Koo Jeong A

Karel Martens

Dazzle rug by Richard Rhys

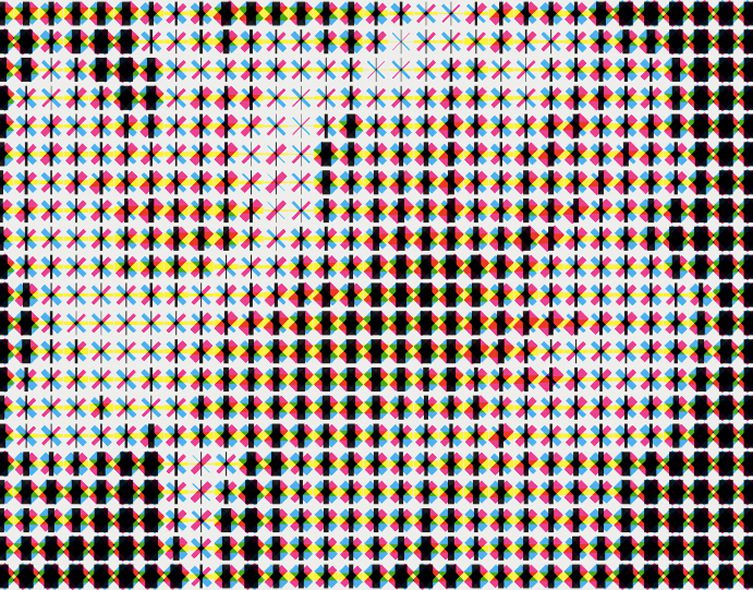

Amorces by Thomas Brinkmann

Digitally printed on crêpe de chine.

Inspired by the mathematics of a curved three-sided triangle found in the Alhambra Palace in Grenada, mathematician Du Sautoy worked with Rhys to create a pattern that played with the shapes of the curves, distorting the original shape into something playful and ghostlike. There’s a mischievous element to the pattern, and Rhys explains that each order contains a single tile that includes glow-in-the-dark eyes, tapping into Du Sautoy’s enthusiasm for engaging with mathematics in a playful way. There’s a similar playfulness in musician Thomas Brinkmann’s pattern, which refers to the 8 bits that make up a byte using the shape of toy gun caps, also offering a dual interpretation as flowers.

Part of the charm of these patterns is the way their individual context changes the interpretation of the pattern, and Rhys is keen to emphasise the importance of the story that goes alongside each pattern. “You may like it because of the way it looks, but you might be somebody that would want to find out what the context of it is, and maybe that changes your point of view on it,” he says. “This doesn’t alienate people. Anybody could look at something and say ‘maybe that’s familiar’. It was lovely, this realisation that there’s a story behind each pattern. A reason why it exists, and not just as for pure decoration sake.”

Although the company is approaching its tenth year now, Rhys explains that its gradual development has been an important opportunity, allowing the studio to grow at an organic pace and without pressure. Having recently launched their website, however, Rhys is keen to expand the practice in both its scope and its potential collaborators. This includes exploring new mediums for the patterns, and although tiles turned out to be a perfect starting point, Rhys is keen to experiment with different end products, and has also developed rugs and textiles. “It’s all about experimentation – the way things can work and ways they don’t work out. The first generation of patterns were digitised for that openness, where they didn’t have anything application-wise in mind,” he says. “And there’s another phase that exists for a particular application, and surprises do happen. They can lead to other objects that were not first intended.”

Karel Martens

Ghost by Marcus du Sautoy

Tide by Wim Crouwel

Karel Martens

The studio isn’t just focused on commercial productivity, however, but also functions as an ongoing research project and archive. “You could look at the whole thing as a meditation on pattern, and a way to explore so many different facets of it through making products and various projects that we have been and could be involved with,” says Rhys. “These projects don’t necessarily have a commercial objective. A pattern will come out of it and that’s important, because that feeds back into the products and informs new work. Organic development over the years is key.”

The name, and to some extent the purpose, of the Pattern Foundry found its first inspiration in the world of type. “I was interested in that point where the meaning of the word ‘foundry’ conjures up this notion of pressing and making things: the type and the fact each physical letter is a moveable and modular item,” says Rhys. “It’s a simple idea in some sense: instead of typography you’ve got patterns.” This has also fed into the foundry’s commissioning process, with Rhys working with typographer and type designer Wim Crouwel to use his letter gridded forms to create patterns.

The collaboration with Crouwel is a perfect example of Rhys’s curatorial process, with many of PF’s pattern projects and collaborations coming about via recommendations from other people. With the launch of the website and the growth of the foundry, there’s now a new freedom to go out and engage with potential collaborators and customers.

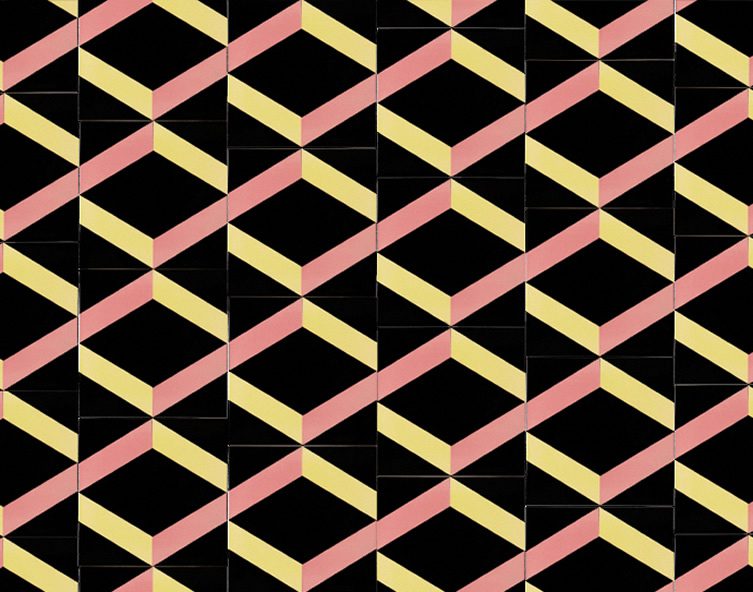

Afrikö by Körner Union

Screen printed on white satin cotton upholstery fabric.

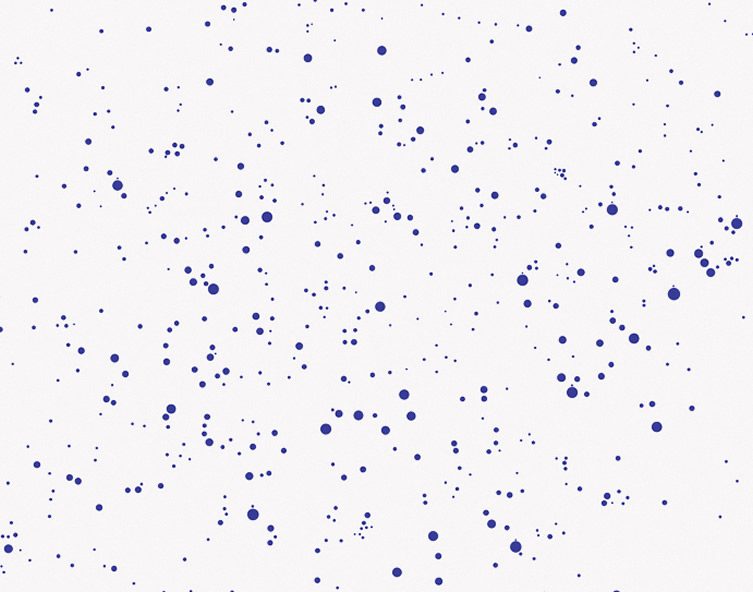

The Universe by Ryan Gander

Bep by Karel Martens

Digitally printed on double faced satin in fluorescent pink.

Although there’s been mostly interior designers and architects who have approached Pattern Foundry recently, Rhys is keen to approach new audiences. “I’m interested in anybody using these tiles, anybody who likes them,” he says. “There’s the idea of enriching these things that are around us at home or at work. I’m particularly interested in domesticity, and I feel that there’s a need for things around us to be improved if even slightly, but not for things to be too much.” He goes on to explain that, although the home is the most traditional setting for tiles, he wants to push their use into more unexpected ways and places.

Aside from functioning as an incredible resource of work, Pattern Foundry taps into a growing need in the creative community to return to a sense of craftsmanship and production of tangible goods, with more designers and imagemakers moving above and beyond two dimensions to experiment with textiles and objects. It’s this sense of the ephemeral turned into something tangible that makes up the foundry’s appeal, and as Rhys says, “I don’t know what it is, it’s mystifying to me, but it’s really thought-provoking. The idea of that translation or transition of putting something that’s drawn or digital onto a material, and the way it comes alive is constantly fascinating to me.”

***

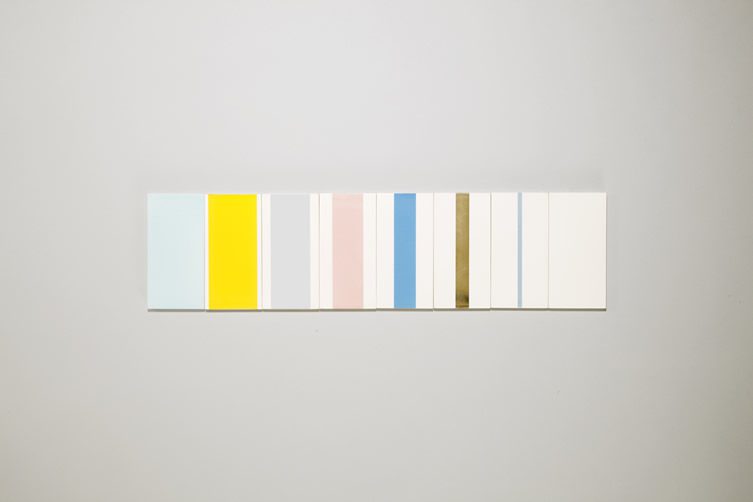

Duo by Karel Martens

Wisp by Wim Crouwel

Easy chair upholstered in white satin cotton.