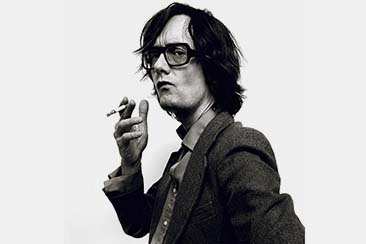

Russian prisons are some of the most notorious institutions around, with a fearsome reputation for inhuman brutality. Woe betide those criminals who find themselves thrown to the wolves caged within their walls – but spare a thought too for those whose jobs involve spending time there among the thieves, rapists and murderers. As a senior expert in criminology at the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs, Arkady Bronnikov spent over 30 years visiting correctional facilities in the Ural and Siberia regions – work that now takes the shape of captivating publication, Russian Criminal Tattoo Police Files. Through interviewing and photographing inmates, Bronnikov built up an amazing body of knowledge on the previously secretive practice of prison tattooing, learning about the symbolism involved and how a convict’s ink tells their criminal history as clearly as any rap sheet, advertising their horrifying and violent predilections.

In the Soviet prisons, as today, thieves ruled the roost. But these thieves, or “vor” in Russian, are not the petty criminals we give the name to. Vor take possessions, yes, but in many cases they also take much more from their victims. Members are inducted into an organised crime movement in the same way as men are “made” in the Italian Mafia, with ranks within the hierarchy dependent on the severity of the crimes perpetrated (ranging from breaking and entering to rape and murder) and the number of convictions received. The Thieves-in-Law have a strict code of conduct that must be observed, including following the chain of command, with subordinates carrying out prison beatings, rapes or killings at the behest of the top dogs, ruled absolutely by the “pakhan”.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

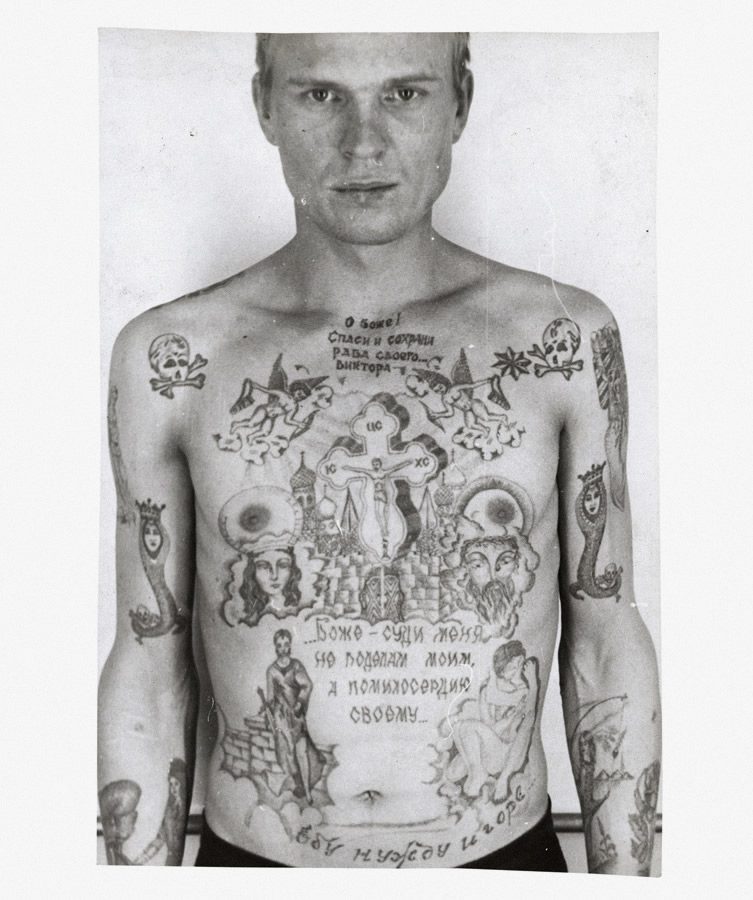

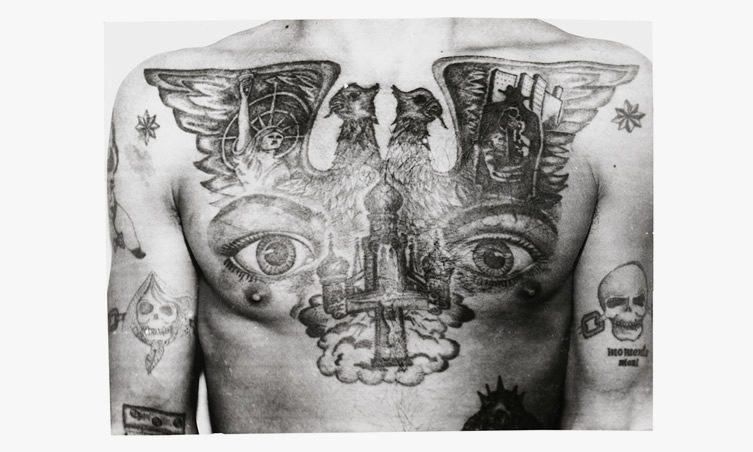

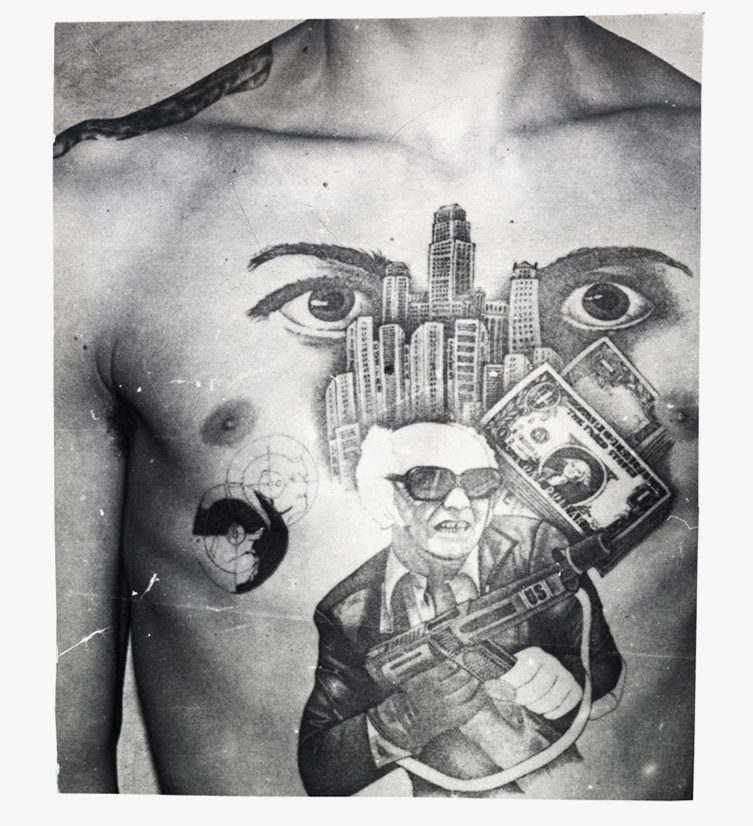

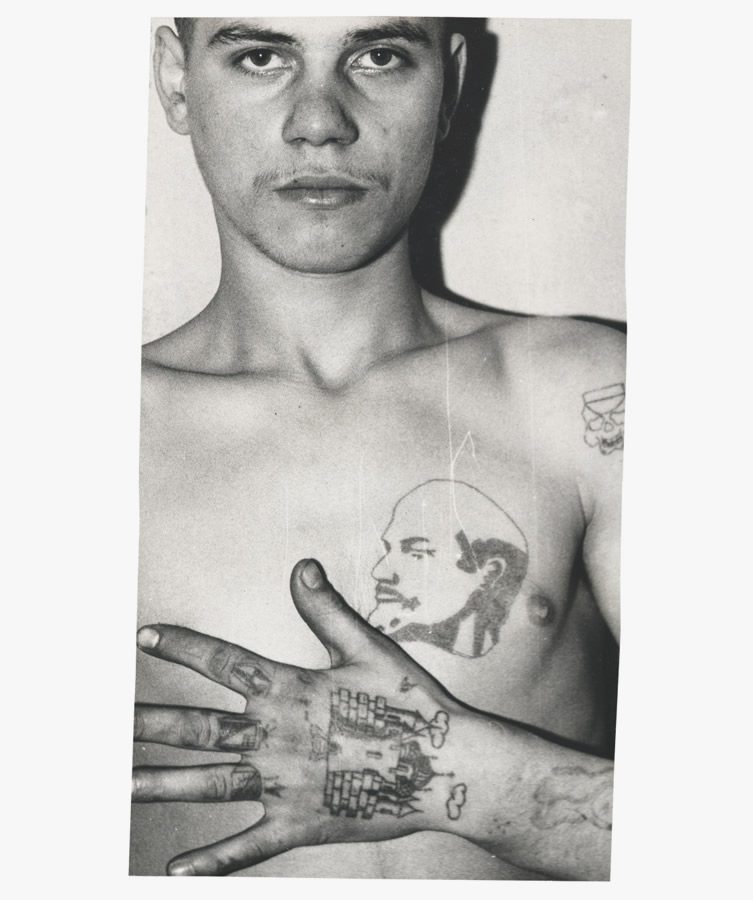

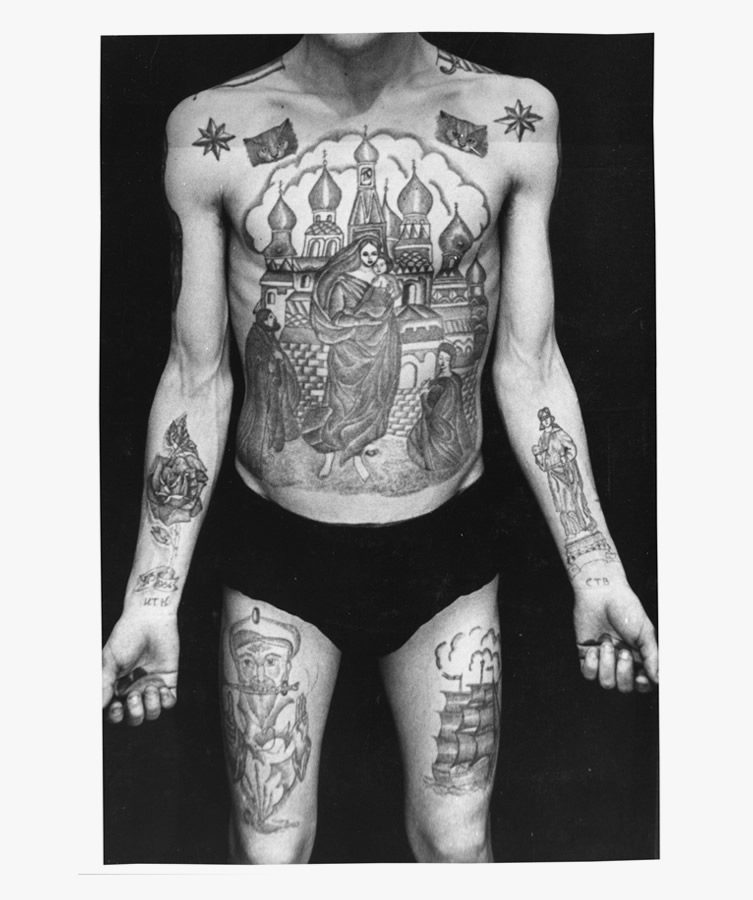

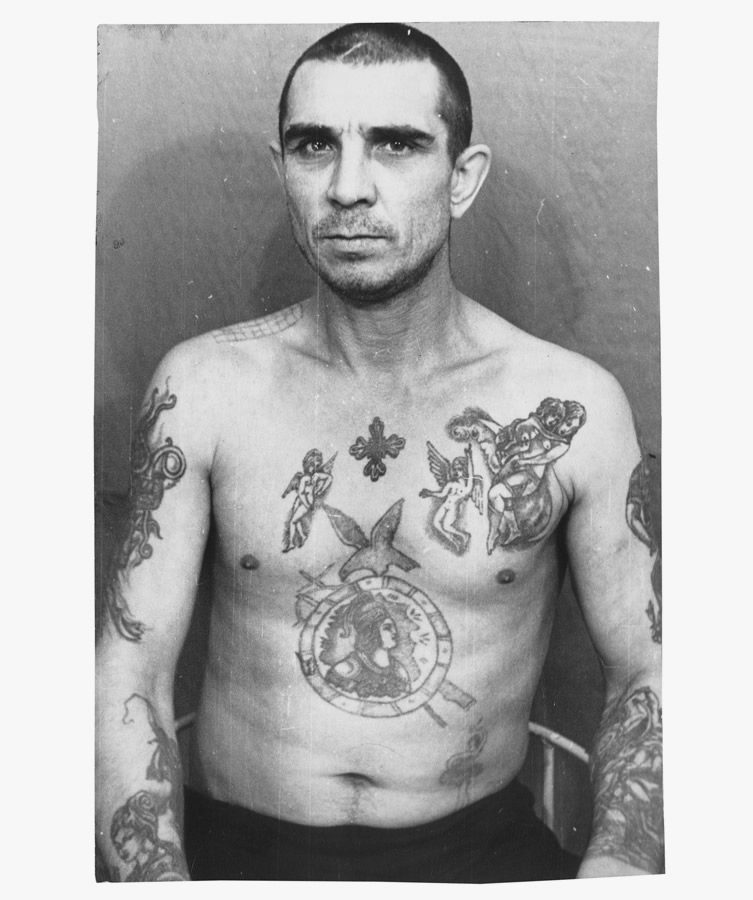

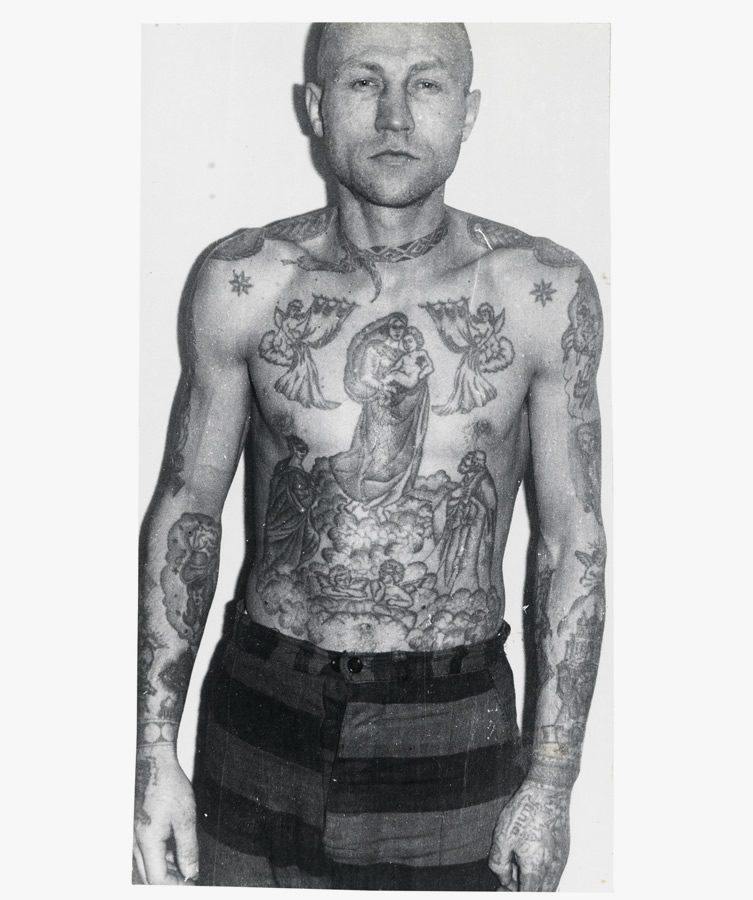

Although junior inmates or wannabes may also wear vor-style designs, the mark of a true Thief-in-Law is the star tattoo. This signifies that he has met the conditions of entry into the organisation, done his time, and done his crimes. Most vor bear a large image on the chest – usually a church or large cross, symbolising their devotion to the thieves’ way of life and that they are pure (or uncooperative with the prison authorities). The number of cupolas on a church signifies the number of convictions the inmate has received. Another popular mark are eyes placed on the upper chest, meaning that the wearer is ever vigilant and all-seeing, ready to severely punish transgressors. Cat’s faces – a seemingly innocent design – hide a more sinister meaning. They convey that the convict likes to enter a home quietly to steal, but it can also signify a rapist’s preference for strangulation.

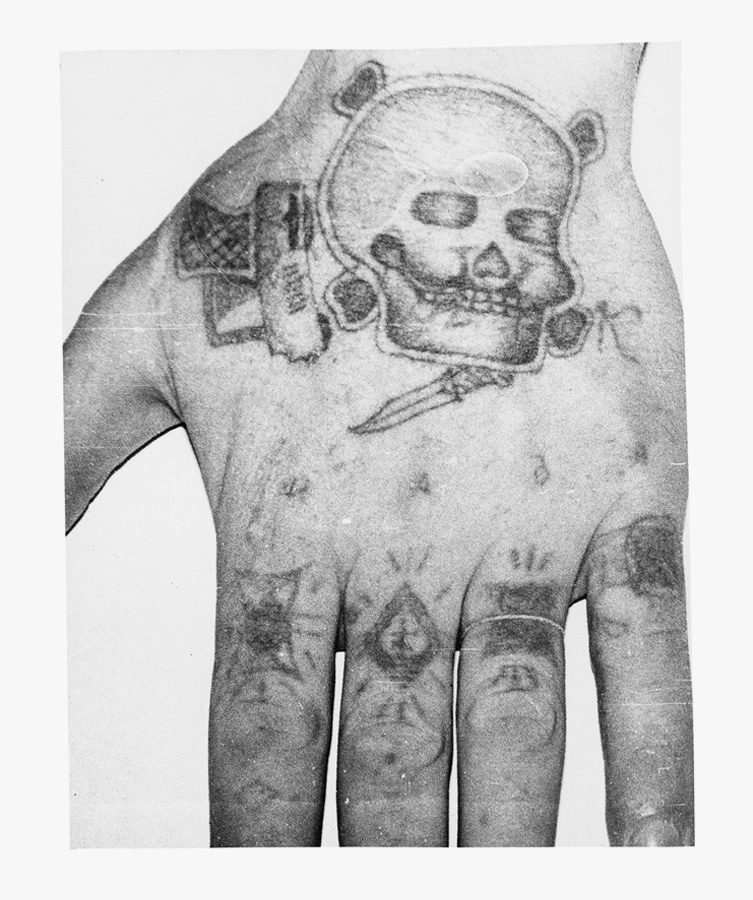

As well as text slogans, finger tattoos are a common way of getting a message across. Designs recorded by Bronnikov include those indicating rank, much like an army officer’s shoulder stripes, messages about brotherly loyalty, whether a full sentence was served without parole, and time spent in solitary confinement. In contrast to the fleshy, well-muscled body parts, eyelids present a uniquely unpleasant place for a prison tattoo. A metal spoon is inserted underneath the skin to prevent the needle puncturing the eyeball. Eyelid tats carry messages such as the blackly humorous “Do Not Wake” in readiness for their death.

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

Even seemingly straightforward political declarations carry a meta meaning when worn on a convict’s body. Lenin is held to be the chief pakhan; he presided over the communist movement which many criminals blame for their impoverished upbringing, stealing property for the state and murdering his opponents. His image is often accompanied by an acronym standing for “Leader of the October Revolution”, but which also spells out VOR.

Following the acquisition of Bronnikov’s archive, which includes photographs and official police papers from the Soviet era written by the man himself amassed from the 1960s to the 1980s, FUEL is presenting the highlights in a two-volume publication. The first part of Russian Criminal Tattoo Police Files is available now directly from the publisher, and there is also an exhibition of material from the archive on display at the Grimaldi Gavin gallery, London, until 21 November.

@FuelPublishing

@GrimaldiGavin

***

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL

© Arkady Bronnikov / FUEL