Maybe it’s the hardcore at CBGB; Reed waiting for his man; Warhol’s Factory; Blondie pioneering new wave, disco giving guitars groove. Maybe it was watching ’80s TV movie The Children of Times Square as a kid, seduced by the grit, the lights, the danger. The serial killers; Central Park’s flashers; Studio 54; Talking Heads; Larry Levan; Peep Shows; François K; Escape from New York; Arthur Russell. Coming to America. My obsession with pre-Giuliani New York is formed from a mismatch of news reports, the music I adore, movies using the city’s decaying veneer as a backdrop for tales of crime and despair, the decadent daydreams of a young punk growing up in small town Britain.

It’s easy to be seduced by the apocalyptic allure of ’70s and ’80s New York City, but living it was surely a tougher feat. Drive around parts of east Brooklyn today and there is still an acute whiff of danger to be smelt, even Bushwick – with its hipster bars, artist residences and street parties – still retains more edge than most creative playgrounds. Imagine walking its streets at the turn of the 1980s, the hangover of 1977’s riots still being felt. Imagine having documented Manhattan’s most debauched nightlife before arriving for your new teaching post in the decaying neighbourhood. Imagine the contrast, the disparity. Starting work at Bushwick Public School, illustrator and photographer Meryl Meisler had been privy to the polar opposites that New York dealt: photographing the revellers of the famous clubs that pioneered disco, her new job meant that decay was her new muse – an unravelling neighbourhood the subject to replace drag acts, celebrities and decadence.

In A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick, Meisler pairs her powerful portraits of the crumbling Brooklyn neighbourhood she called home alongside a goldmine of candid shots from her days riding high on the crest of New York’s nightlife scene. Published by Brooklyn’s Bizarre Publishing, the 180-page monograph serves as a document to the parallels of disco-era NYC that ensnared the heart of my young self; vice, hedonism, crime, vice, hedonism… I spoke to Meryl about living my dreams, about the worst of times, about today’s Bushwick. From the Paradise Garage to despair, welcome to Meryl Meisler’s New York City.

Two 4 One Muscles

Les Mouches, NY, NY, May 1978

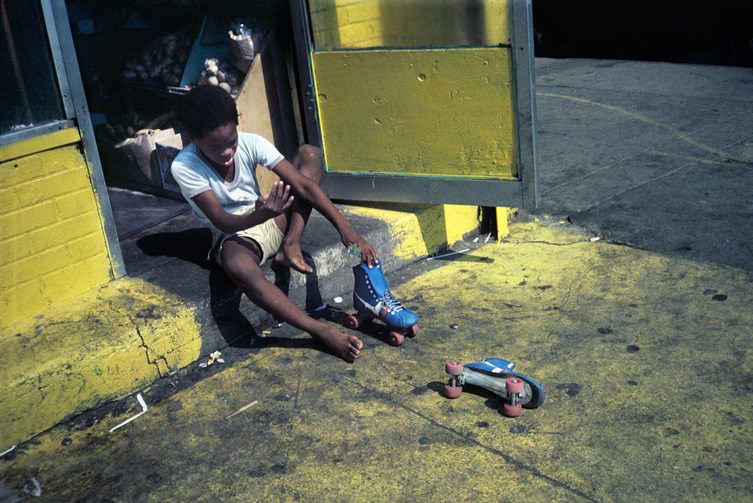

Roller Skates

Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY, Circa 1984

Growing up in the ‘80s on the other side of the Atlantic, New York had a mythical appeal: killers lurking in Central Park; Times Square’s peep shows; no-go-areas; frighteningly good music – I can’t remember when exactly I fell in love with the idea of this era, but it’s stayed with me all my life. Can you tell me a little about what it was like living there at the time?

I was born in The Bronx and grew up in Long Island. My dad Jack Meisler had Excel Printing Company in Chelsea. My mom Sunny and dad often brought my brothers and I into “The City”. Yet, I was scared to live there when accepted to grad school at Columbia Teachers College because of tales of violence and chose to go to Univ. of Wisconsin in Madison instead. In 1974, after grad school I sub-letted a room in my cousin Elaine Rosner’s brownstone on the Upper West Side. I wanted to study photography with Lisette Model and start a career as a freelance illustrator. My love of NYC has never withered. I feel at home and have never known boredom. In the ’70s and ’80s I carried my camera most everywhere. I have an incredible archive of street scenes throughout the boroughs, and more nightlife that will start being revealed soon. Stay tuned.

In the 1970s, I lived on 92 St., right off Central Park West. I’ve always been cautious about safety and would not walk or run in the park alone. The first time a flasher showed me his private parts in Central Park was the last time I ran there. Perhaps that was my excuse not to run in general. June 1981, on the last day of teaching at a school in the Lower East Side, an intruder threatened he had a gun and told me hand over my beloved medium format camera. I did. In 1984, my life partner and I moved to an apartment in Park Slope, right off Prospect Park. It was a really nice area, but the park was a place for thieves to do their dishonest business and hide. In the 18 years we lived there, our apartment was robbed two times and she was once pistol-whipped in the front lobby for her pocketbook. A roommate who shared another apartment I rented for an art studio was followed into the building at night, tied up and I was robbed a third time The intruder was waiting for me to come home, Fortunately I never went to the studio that night. The roommate quit his job and left NYC, forever. In those series of burglaries I lost a lot of camera equipment and jewellery from my mom and grandmother. As my mother said; those things are “only money”, I was never physically harmed.

Still, I loved New York City — the diversity, freedom (with caution), and adventure, diverse brilliant talented people from all corners of the earth calling NYC home. I photographed the everyday street live and the wildest nightlife scenes. Yes, there were lots more Go-Go Clubs, Peep Shows; I knew people who worked there and photographed them too.

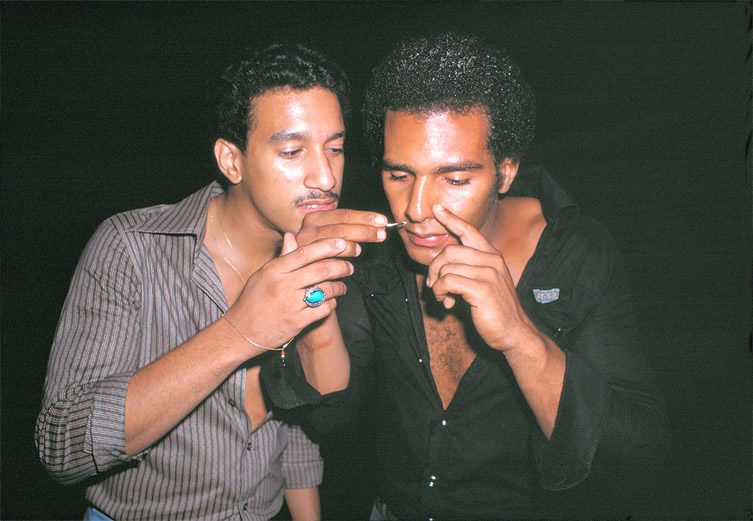

Turquoise Ring

Studio 54, NY, NY, August 1977

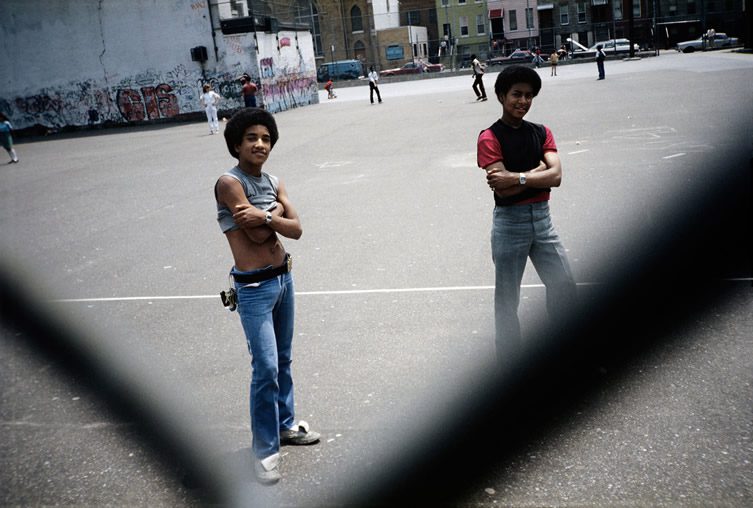

Jose and Classmate in Schoolyard Chillin’

Bushwick, Brooklyn, June 1982

What made you start taking your camera to the likes of Studio 54 and Paradise Garage — and did you ever encounter problems when photographing people; i.e. were people happy to be captured shoving cocaine up their noses?

A friend I met at Mardi Gras 1977, Judi Jupiter, and I started going to the CBGBs and then soon after the discos together. We went to the hottest clubs in Manhattan and during the summers, Fire Island; of course my camera came along. There were lots of photographers at the discos, paparazzi hunting the celebrities. People were there to be seen. Once, when standing on a low divider wall photographing at the Fire Island Ice Palace in the late ’70s, someone shoved me intentionally off the wall. They were probably not comfortable with the possibility of being documented in a predominantly gay club. I usually ask or gesture for permission to take a photograph, then and now. If a person gestures no, 99.99% of the time I don’t take the photo.

Stuffed Lion Down

Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY, October 1982

Star Wars Party

Fire Island Pines, NY, August 1977

Last Wall

Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY, June 1982

The influence of the music and the attitude of disco still reverberate in today’s culture; did it feel at the time like something special was happening?

Oh yes, it felt like a special time and place. We are talking just a few short years after the era of Folk Music, Woodstock Festival. The “hustle” dance craze was going in the early ’80s. By the time Studio 54 opened in spring ’77, there were throngs every night hoping to be let through those red velvet ropes. But, if our favourite doorman Marc was not there to welcome Judi and I in, it was an opportunity to check out Paradise Garage or dozens of other clubs popping up all the time. The music, sound systems, and environment of the nights were fabulous, great places to dance to your heart’s delight.

Of course, not all glittered in the disco era – you found yourself in Bushwick in 1981, the Brooklyn neighbourhood exemplifying inner-city degradation. What was the mood like amongst the people?

To me, moods are very personal, deep experiences, instance-based or genetically prone conditions. Sure, there might be a general state of sadness or despair when disaster strikes a community (think 9/11, Hurricane Sandy) and Bushwick was suffering greatly from the multiple sociological, political and economic conditions that led up to the riots of ’77. Still, people live their lives, do what they have to do, seek and hopefully find laughter, love and friendship.

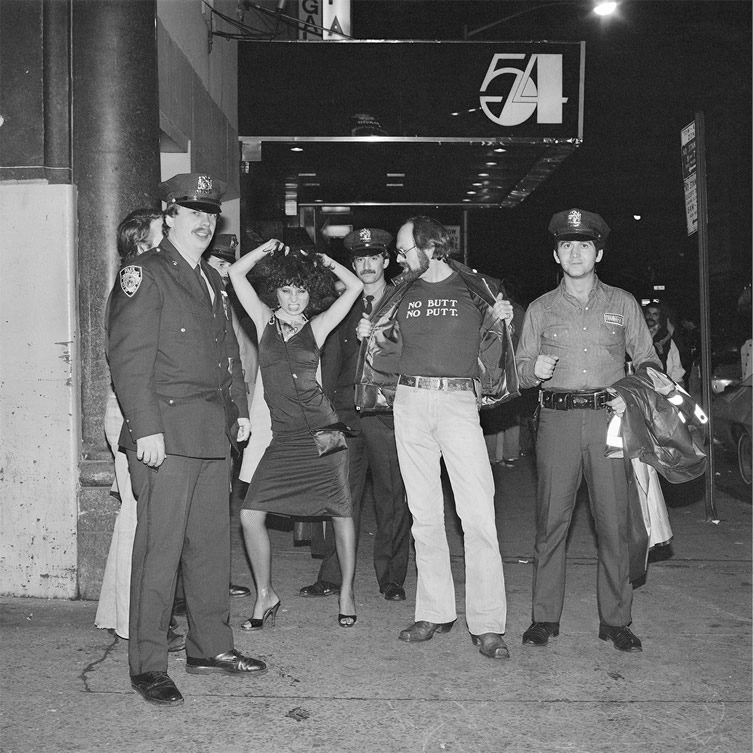

Rejected From Studio 54 No No

Studio 54, NY, NY, October 1978

Two Girls Strike a Pose

Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY, June 1986

The book is titled A Tale of Two Cities, is this how it felt at the time – how far away did the degeneration of Bushwick feel from the bright lights of Manhattan’s nightclubs?

The physical conditions of the neighbourhood were more extreme than any I’d visited, even the South Bronx. It was the polar opposite of the wild nightlife scene. I wasn’t partying or visiting, I was working really hard. Teaching was very challenging to me, classroom management always a struggle- point blank. Going out late at night was no longer an option. I had to be “in control” of energetic mischievous youth at 8am. My interest in learning more about the neighbourhood drove my art curriculum. By networking with other socially motivated arts educators “Artists Teachers Concerned”, the students’ collaborative work was exhibited in The New Museum, Dia Foundation and included in a Whitney Biennial. I didn’t quit.

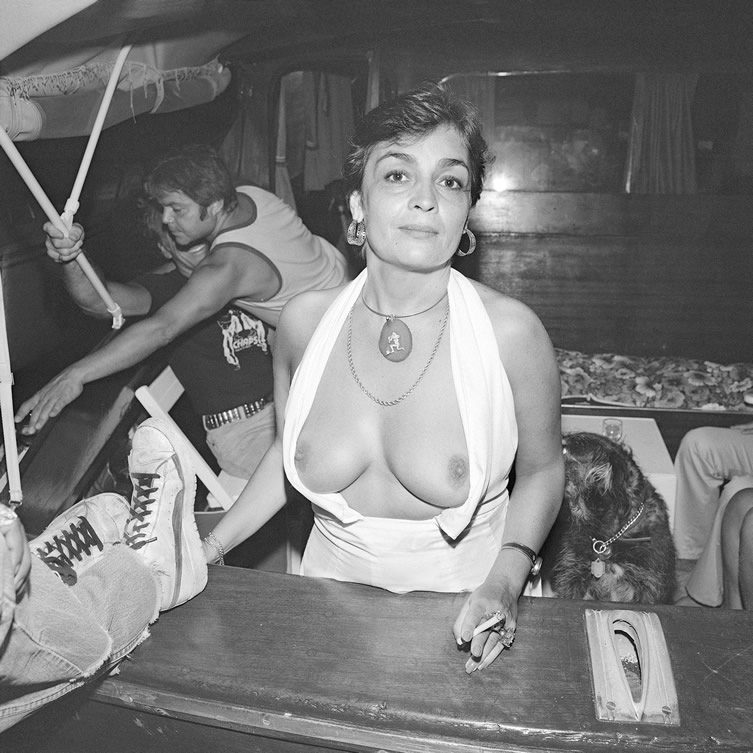

Bare Breasted Bartender

Ice Palace, Cherry Grove Fire Island, NY, September 1977

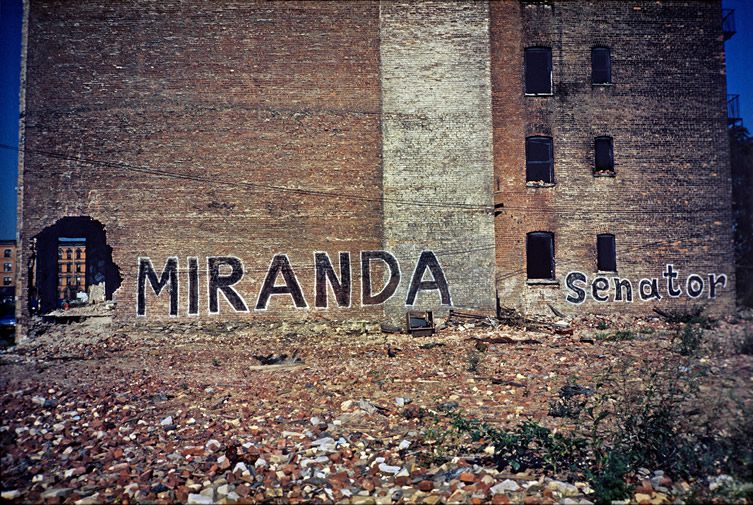

MIRANDA Senator

Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY, October 1982

Over thirty years have passed and the gentrification of Williamsburg has pushed its cultural inhabitants out to the neighbourhood you documented in decline all those years ago, what do you make of what’s happening in Bushwick now?

I don’t wax nostalgic for danger and despair. Lots of empty lots once filled with crack vials and needles are cleaned up and new housing is going up. To me, the most successful newer buildings are those that are consistent with the scale of existing lo-rise housing stock. There is a wonderful feeling of creative energy in Bushwick and I am fortunate to be among its extended arts community. People are moving in or visiting instead of running away.

As a “middle income” working artist/educator, I have been able to live in NYC all these decades because of job stability, rent stabilisation and now living in a socialist affordable housing community in Chelsea. The dangers of gentrification include displacement and sanitising the unique character out of a neighbourhood. Bushwick and all of NYC (and beyond) must nurture, preserve and create more affordable housing, progressive public schools, health and social services, employment training and opportunities for both long standing and new residents, youth, adults and elders alike. Respect, dignity, empathy, compassion and safety must be everyone’s assessable right and obligation. Please, exercise your power to vote.

***

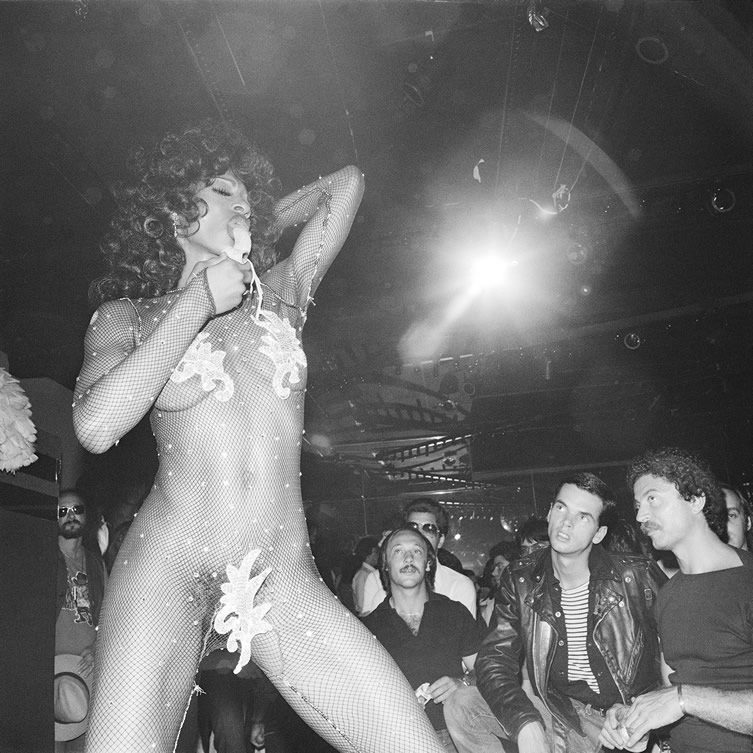

Send In The Clones Performer

Les Mouches, NY, NY, June 1978

Snow Alone

Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY, April 1982