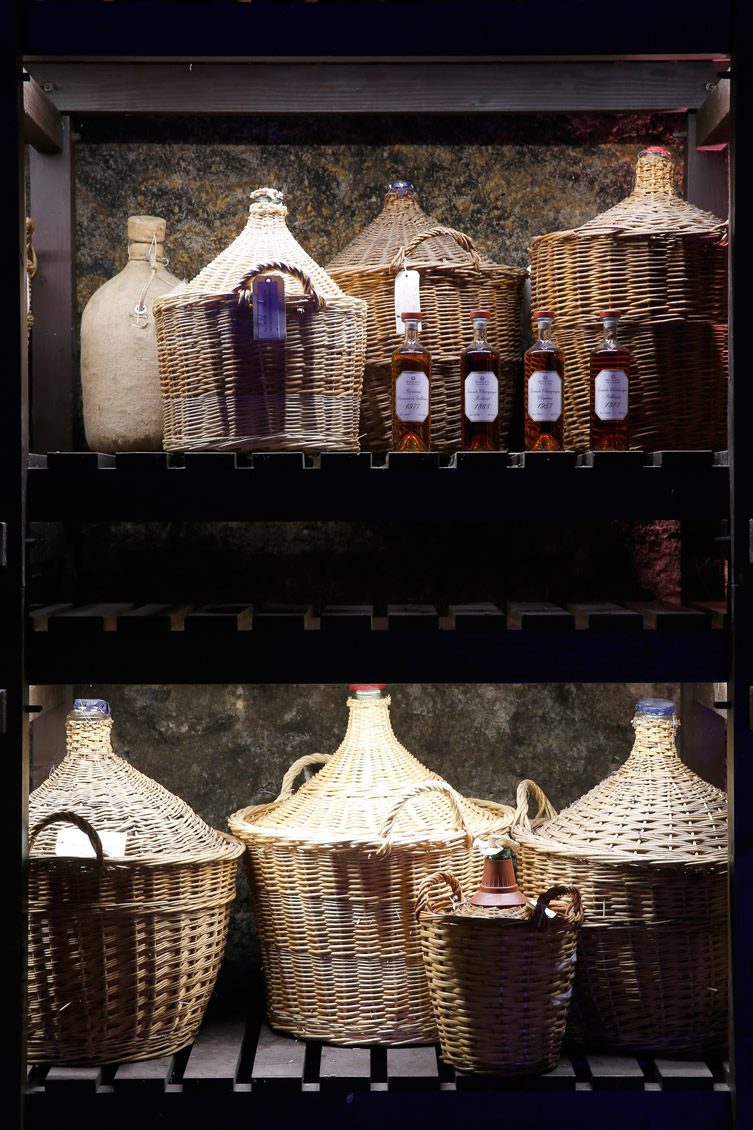

An unassuming cobble-floored storage room in Martell’s Cognac headquarters, just north of Bordeaux. It’s not very warm in here. It’s also dark, which leads to much tragicomic stumbling as we enter — and perhaps even a little more as we leave, a couple of glasses of cognac heavier. There are some tastefully-lit cabinets at the far end of the room displaying prestige special edition cognac blends, but otherwise it’s spare and utilitarian.

Diane Kruger and Philippe Guettat

(Chairman and CEO, Martell Mumm Perrier-Jouet)

Rows of large, unadorned oak barrels stretch thirty yards or so down the length of the bare concrete floors. The walls are pockmarked with a fungus called Torula compniacensis that thrives wetly on the escaping alcohol (this lost booze is called the Angel’s Share). Outside the skies are grey. There’s a constant threat of drizzle above the town and above the green-and-brown corduroy countryside, whose chalky soil springs with vineyards.

Later, by contrast: a luxury fifth-floor room in The Peninsula, Paris. The Eiffel Tower looms outside, larger-than-life as she always is, a grimy and unimpeachably elegant fin de siècle glory. Inside, the room is all marble-slicks and polished wood and gilded full-length mirrors that have the unusual but frankly excellent quality of making even me look like Jay Gatsby. The bathroom has more moving parts than a fighter jet, and that’s not an inapropos comparison: from here we’ll be driven to Versailles, where a lavish formal dinner — Diane Kruger is there, as well as Solange Knowles, Naomi Harris and a host of others — will be inaugurated by an exclusive fly-past from the Patrouille de France, their version of the Red Arrows; a big, big deal indeed. All this is in celebration of the 300th anniversary of Martell, the oldest of the great cognac houses.

Cognac, France

The contrast is what I keep coming back to. That’s always the thing with luxury: it sells mostly to the wealthy, the pampered, the slick, but it comes from the artisanal, the traditional, the real. The drink greeted by exclusive celebrations at one of Europe’s great palaces begins in the mud of the field, with grime under the fingernails of someone who can tell a lot from the heft of a bunch of grapes. Real luxuries are glossy and opulent but founded in the hands, the eyes, the noses, the mouths, the generations-old expertise of people who live the things they make. It’s certainly so with cognac.

Like champagne, ‘cognac’ is an Appellation d’origine contrôlée, so its provenance is always in the gently undulating fields and hills of Charente and Charente-Maritime, the regions surrounding the town of Cognac. Its home is these vineyards, natural springs, plain farm-buildings and occasional chateaux. Within Charente and Charente-Maritime there are six subdivisions that each produce grapes with their own distinctive character, which are pressed and distilled to produce eaux de vie that are then aged, blended and matured. There are a lot of cognacs out there: the big four houses that you’ll have heard of, including Martell, and lots of other, smaller producers. But they’re all here, because this is the only place on Earth where cognac can be made.

Martell is distinguished in three main ways. First, it uses grapes from only four of the regions — Grand and Petite Champagnes, Borderies and Fins Bois — and emphasises in its blends eaux de vie from the smallest and most prestigious of them, Borderies. This makes for cognac that’s light on its feet yet powerful, fruity and floral. Second, it insists that its wines are without lees, for distillings that are clearer and less heady. Third, it ages the cognacs in fine-grained oak, which is less porous and releases its tannins to the alcohol slowly; this is essential for the meticulously controlled maturation that results in subtlety, profundity and depth. Martell’s spirits might not always have the dark hues that the uninitiated associate with quality, but their muscular, restrained gleam and immaculate flavour tell a more impressive story.

In the Martell facility in Cognac we’re introduced to Bertrand Guinoiseau, whose title — International Heritage Brand Ambassador — sends a shiver of corporate propaganda-averse dread down my spine. I’m ready to take anything he says with a hefty pinch of salt, as well as any other of the seasonings customary in this part of France. But despite the tailored suit and refined charm, he’s no marketing mouthpiece. He’s been with Martell in various capacities his whole 36-year career, which starts to convince me; his father before him for forty, which does the rest. When asked if he’d leave for more money from a rival house he looks thrown, as if he’s not sure he’s understood the question.

‘Um … non,’ he says eventually and with incredulousness at the thought. ‘Never.’

Martell House

Guinoiseau’s is far from the only family connection. The cognac industry employs hundreds of thousands here, from cellar-masters to coopers to bottlers to grape-growers, and there is a dense network of generations-long lineages and affiliations. Some families have been selling to or serving Martell for generations, and until the 1990s the company itself had never been headed by anyone other than a Martell.

Dinner at Versailles

When the company was planning its commemorative tricentenary blends no heritage stone was left unturned. For one cognac they consulted their 300 years of exhaustively archived documents to select eaux de vie that reflected Jean Martell’s original sourcing; another blend combines three vintages with dominant notes linked thematically to the past three centuries of Martell’s cognac-making. These and other blends were then aged in casks made from specially-sourced, 300-year-old oak from the Bertranges Forest in Northern France, cut in February 2011. The history of dusty ledgers and aged wood and family loyalties and gritty, chalky earth is palpable here — even if some of these bottles cost upwards of €10,000 and end up untasted on trophy shelves thousands of miles away.

Which brings us back to Versailles. Here there’s little mud, and no fungus; everything is made of marble and sandstone and gilt, and has a glint in its eye that speaks of centuries of privileged poise. The tuxes are elegant, the dresses spectacular, the cocktails expert, and the majority of us likely couldn’t tell a Borderies eau de vie from a Petit Champagne if our lives depended on it. There’s a lavish banquet produced by Paul Pairet, who has been drafted in from Shanghai for the occasion: we eat DIY lobster rolls with aioli and asparagus (the ingredients are presented to us in individual wicker hampers), tee-weed oyster and scallop melba, teriyaki lacquered beef. Before dinner there’s the aerial display from La Patrouille de France, afterwards an elaborate fireworks performance in the grounds. During a packed press-conference Diane Kruger gushes about Martell being the embodiment of French Art de Vivre — it’s what she serves at her dinner parties in LA, she says. I’m having a great time, and consuming enough fine food, wine and cognac to pay my rent in the UK for six months.

But, really, I felt better about the musty concrete bunker from earlier in the day. Particularly, I’m thinking of the fine grains of the oak, three centuries of tight concentric rings only recently brought to light, exposed first to the air and then to the unmatured alcohol with which they will bond aromatically for years. I can feel the wood’s roughness still and the sweet, slightly scorched smell of it. Amongst all this razzmatazz, surrounded by journalists and movie stars and models and businesspeople from all over the globe, I’m enjoying the thought that in rolling fields hundreds of miles away there are grapevines in the darkness and expert growers sleeping nearby, ready to tend them in the morning. That there are blends sitting absolutely still in sealed barrels in the dark, changing slowly in precisely the way that the cellar masters have planned.

The party’s great, but it’s only really there to celebrate the other stuff — the real stuff. That’s worth remembering.