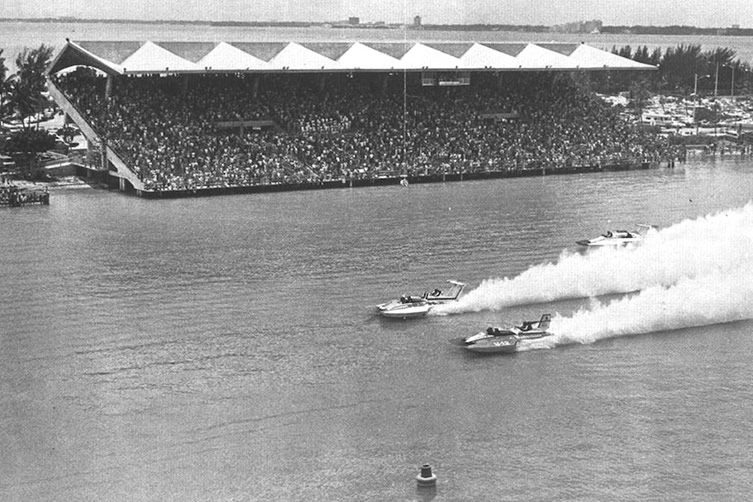

When speedboat racer James Tapp died, 27 December 1963, some may have predicted an unsettled future for Miami’s latest entertainment arena; the inaugural event at the United States’ first purpose-built boat-racing stadium getting off to a bad start. Happenings hosted by Sammy Davis, Jr., President Nixon, and all-American icon Jimmy Buffett were just some of the non-water-based spectaculars that graced the Miami Marine Stadium in its heyday, but the tragedy of its opening day returned in 1992, in the shape of Hurricane Andrew. The lights were turned out for good on 18 September — the county declaring the site unsafe in the wake of the storm.

The 20th Annual Budweiser Hydroplane Regatta, 1990, would be the stadium’s final hurrah — but the two decades that have passed since its doors closed have seen the concrete curiosity transform into a canvas for street artists; local, national and international (names like Dabs Myla; RISK; Ron English; The London Police; RONE). Conceived by Cuban architect Hilario Candela, Miami Marine Stadium was poured entirely in concrete and — as reported by American magazine Dwell — its waveform roof was the world’s longest span of cantilevered concrete. A whopping great concrete roof means whopping great concrete posts to support it; swathes of grey, textured graffiti canvas. The overall impression is of a U.S.A. Super-Sized version of Southbank’s long-threatened skatepark.

The juxtaposition of classic urban decay with the natural beauty of barrier island Virginia Key aligns with Miami’s wider contrasts. A city of wealth and glamour; bling and fake tits; guns and crime. Degradation, regeneration. Some of the country’s most expensive new building projects, minutes away from some of its poorest, most dangerous ghettos. There’s something uniquely poetic about this beautiful mess and the hot, sticky, confused city it looks upon.

Formed in 2008, the Friends of Miami Marine Stadium — staunchly supported by local icon Gloria Estefan — have been actively rallying to have the stadium restored, and add a surprising narrative to the landmark’s story. The non-profit organisation are grateful to the graffiti artists for their part in conserving the venue. Hilario Candela — now in his eighties — admires their work: “they have brought new life into the building”, he told PBS NewsHour last year. The original architect is overseeing the group’s restoration plans, and is determined to incorporate the art into the new project. White-washed cultural genocide? Not on their watch.

Now let’s pause for a second, and take that in. An urban redevelopment project that elevates street artists above ‘vandals’? Now isn’t that refreshing? “The urban art community lost an institution when ‘5 Pointz’ in New York was buffed and demolished. This moment is our chance to come together as a community and save a building with a rich graffiti history”, curator Craig O’Neil told The Huffington Post last year, as the ART History Mural Project rolled into Miami Marine Stadium; nine world-renowned street artists taking over the venue in a fundraiser for the redevelopment.

The balance of maintaining the stadium’s original architectural legacy, its current urban decay charm and the design work needed to restore its glory will be as tricky as stabilising all that concrete was just over fifty years ago. But Candela is focussed: “I don’t like to talk anymore about the past. I only want to think about the future of the stadium. And I want the future to be as quick as possible.” Time is indeed of the essence, the group given a limited timeframe in which to raise the $30 million needed to get the Marine Stadium back on its feet.

To what extent the urban art will endure remains to be seen but, unlike poor James Tapp, the Miami Marine Stadium’s pulse is still strong. Buoyed by twenty years as one of the planet’s rarest galleries, the legacy of Miami’s waterside arena will always be imbued by the effervescence of street art — and remains as positive a tale as can be told about the power of the art world’s most affecting medium.

1975 Champion Spark Plug Regatta

Late 1960s

Evening show, 1971

Photographs courtesy, Friends of Miami Marine Stadium

Under construction, 1963

Photography © We Heart

Unless otherwise stated.