‘There must be some consistency,’ Samantha Wall insists. ‘There must be something that remains resistant to change.’

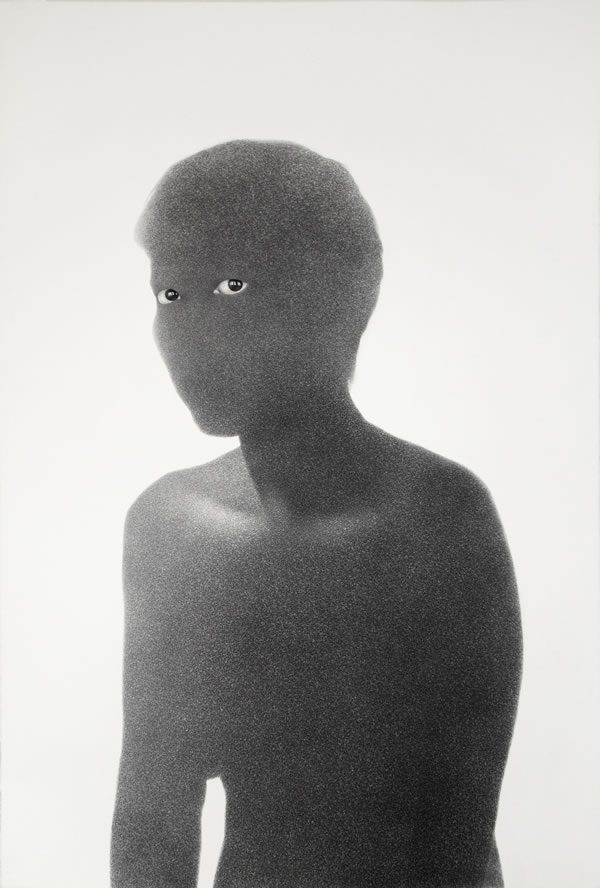

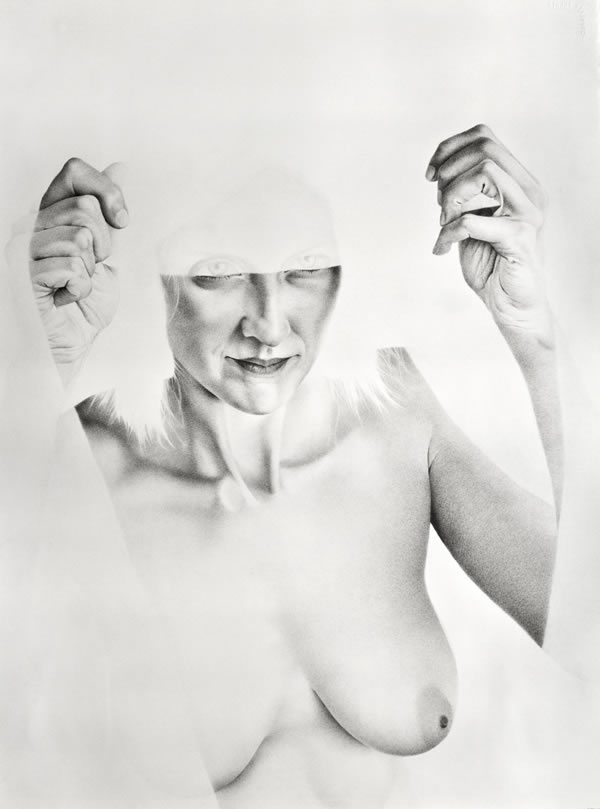

What I Can’t See,

conté crayon, charcoal and graphite on paper,

60″ x 41″, 2014

The fact that this needs to be insisted upon at all is testament to the disquieting power of her work, and the conflicted impulses that feed it: the attempt to affirm and give agency to individual experience, and the attendant anxiety as to whether that’s even possible. The particular series of drawings that prompts this conversation is Let Your Eyes Adjust to the Dark, a collection that presents a number of women’s faces and shoulders, black-and-white on a plain background and obscured by visual distortion, as if a photograph was improperly developed or a watercolour splashed with water.

Actually, though I say ‘obscured’, in fact the distortion looks as if it could be coming from within the faces themselves; the viewer is left fascinated and frustrated, looking hard for something oblique and hidden and unsure from where the disturbance originates. The collection seems to ask questions about the ability of art to render the personal image at all.

‘The series was born out of that exact sentiment,’ she agrees. ‘My previous collection was an attempt to communicate the subjective experiences of other multiracial women (Wall, though Portland-based, was born and raised in Seoul, South Korea) through portraiture. And that was great, but in some cases I became aware how problematic it was, which made me question the possibility of translating one’s subjectivity through a fixed medium — not just because of the limitations of the medium, but because our identities are mutable in themselves.’

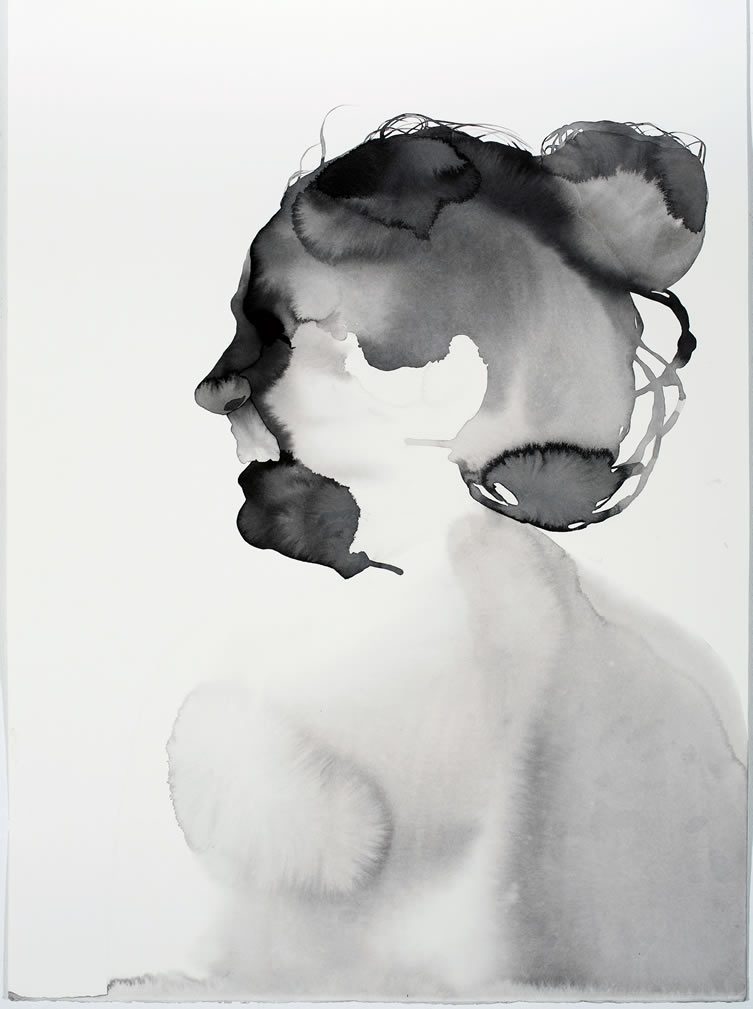

Beauty Marks,

sumi ink & dried pigment on paper,

30″ x 22″, 2014

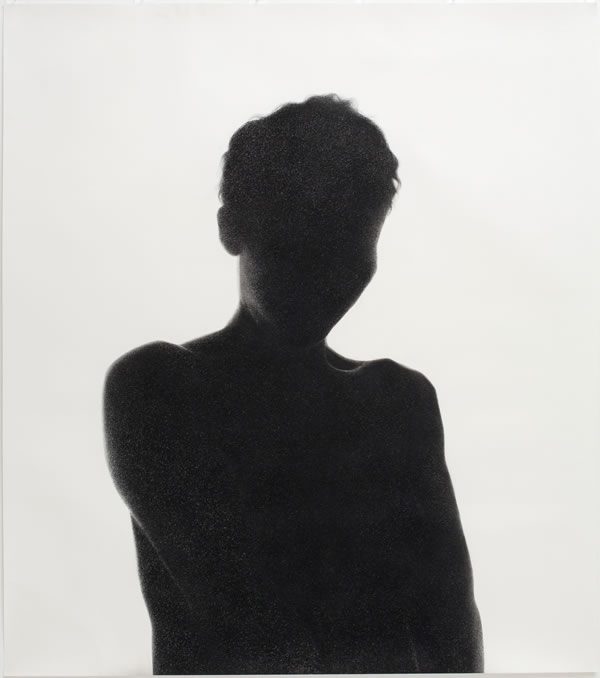

Backbone,

sumi ink & dried pigment on paper,

30″ x 22″, 2015

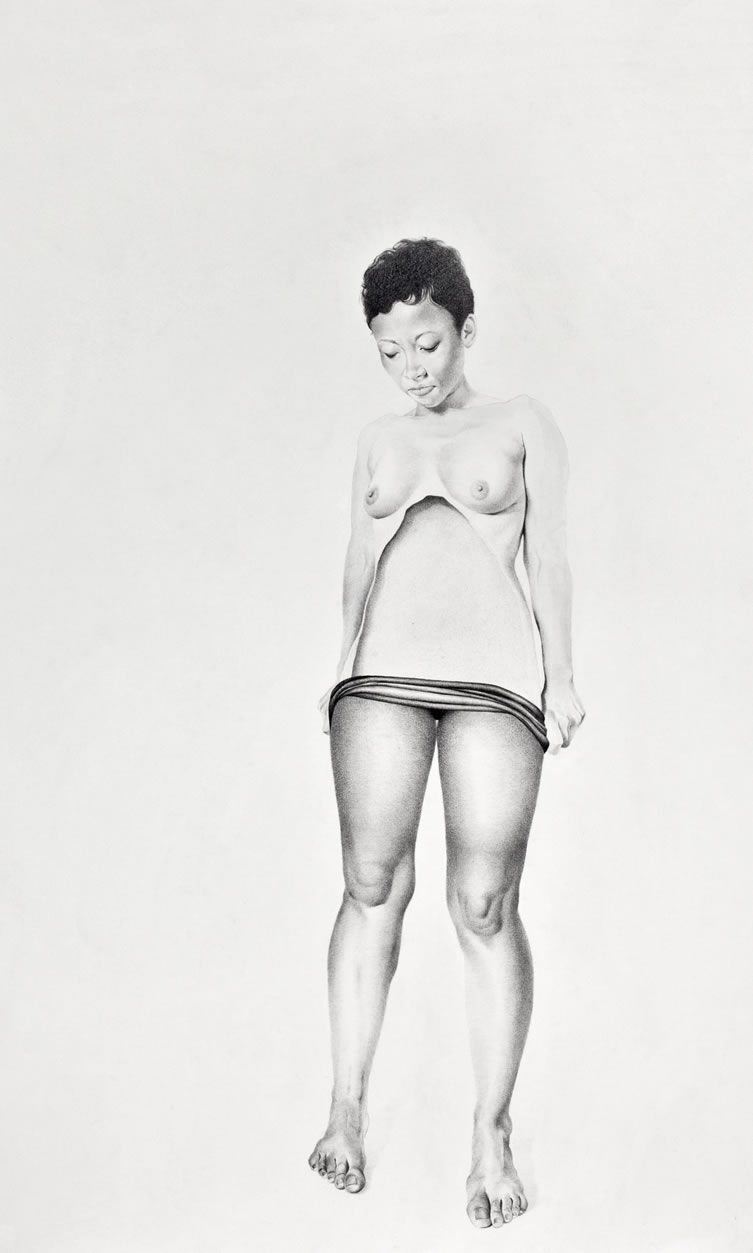

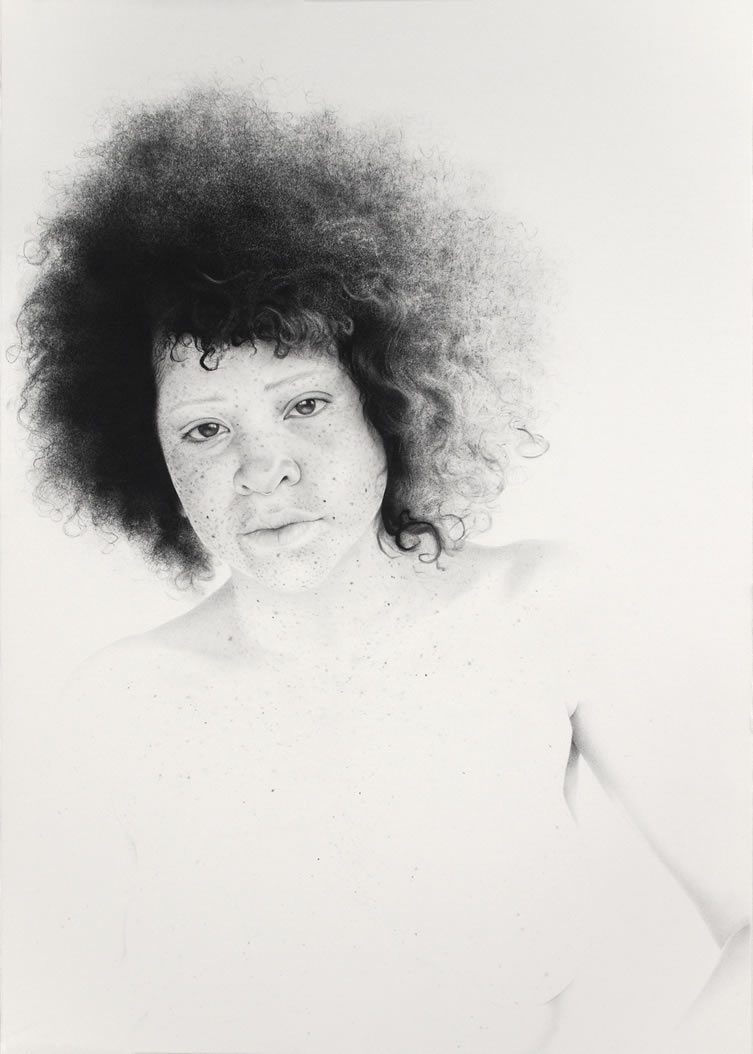

Amelia II,

graphite and charcoal on paper,

22″ x 30″, 2013

It should be noted, of course, that the previous series — Indivisible — is striking in itself. Another collection of female faces and upper-torsos, it consists of drawings Wall made based on her selection of one photograph out of hundreds taken over a single one-on-one session with each subject. They capture joy, confrontation, distraction, alarm, thought, always seeming to seize on a moment that’s just before or after the emotion reaches its full embodiment. In that, it feels like a less aggressive, more benign version of the occluding effect of Let Your Eyes Adjust to the Dark, and I’m interested in the personal process — both of artist and subject — that leads to it.

Flayed,

conté crayon, charcoal and graphite on paper,

84′ x 72″, 2011

‘Part of my process involves taking photographs, often several hundred, and then searching for one or two that capture the quality of that individual, what Roland Barthes might describe as their ‘air’. The photo sessions usually last two hours or even longer, and out of all that one image becomes the kernel or structure for my drawing. It’s the interpersonal connection made between the subject and myself during the photo session that allows me to translate the emotional memories of our shared experiences onto paper.’

But, as in Let Your Eyes …, there’s always the possibility that this translation isn’t fully possible at all. It’s this tension, I think, that gives Wall’s art its power. It’s intensely interested in giving the personal, individual, authentic experience its due, yet is also disturbed by the problems inherent in that project — how can it be done, can it be done at all, has it been done in this case? Much of the tension in the case of Wall centres around the immigrant or multi-racial experience, so I’m curious as to how political her approach is. Inevitably, the answer is conflicted.

Desires and Repulsions II,

graphite on paper,

44″ x 30″, 2011

A Clarion Call,

graphite and sumi ink on paper,

55″ x 34″, 2012

Misconceptions,

graphite on paper,

30″ x 44″, 2011

‘I think it’s difficult to make work that portrays women of colour and not be political,’ she says. ‘But integral to my work is giving agency to the subject — that’s the point, isn’t it, that the individual experience of the often-marginalised not be ignored. So my work is also very personal.’ She pauses. ‘I’m not shying away from the political conversation, but the work is about communicating individuality, acknowledging women who feel unseen, and connecting with other multiracial women who feel alone in their experiences. I think this is the same reason I don’t align myself with any one political or theoretical movement, because I don’t want the boundaries of those movements to define me or my work.’

White Lady,

graphite on paper,

30″ x 22″, 2012

We’ve mostly talked about only two collections, but there are others (notably Partially Severed) which have an impact that’s actually almost terrifying — fittingly, since much of Wall’s inspiration for them came from Asian horror movies, combined with her dedication to forging direct if brief connections with her subjects’ emotional lives. Those collections have led to her sometimes being termed an ‘artist of distress’, but even here I detect more subtlety than that categorisation would imply.

‘I agree. The work is conceived from moments of distress, but I believe the drawings also communicate a range of emotions that are evidence of an attempt to understand that distress. I was inspired by the vengeful female ghost figure from Japanese film because I could identify with her: she’s bound by social, cultural, and familial responsibilities that leave her with little to no agency. She is transformed and becomes the embodiment of her emotions, so by relating my subjects to her I felt like I could investigate both individuality and how it’s threatened by cultural perception and categorisation.’

That seems to sum Samantha Wall up perfectly, to situate her directly at the intersection of individuality and repression, of horror and joyful freedom. Is there a consistency, to return to our original question? Is there something that’s resistant to change? Who knows. What’s certain, though, is the importance of continuing in the attempt to find it, and Samantha Wall’s work certainly does that.

Amelia III,

graphite and charcoal on paper,

29.5″ x 41″, 2014

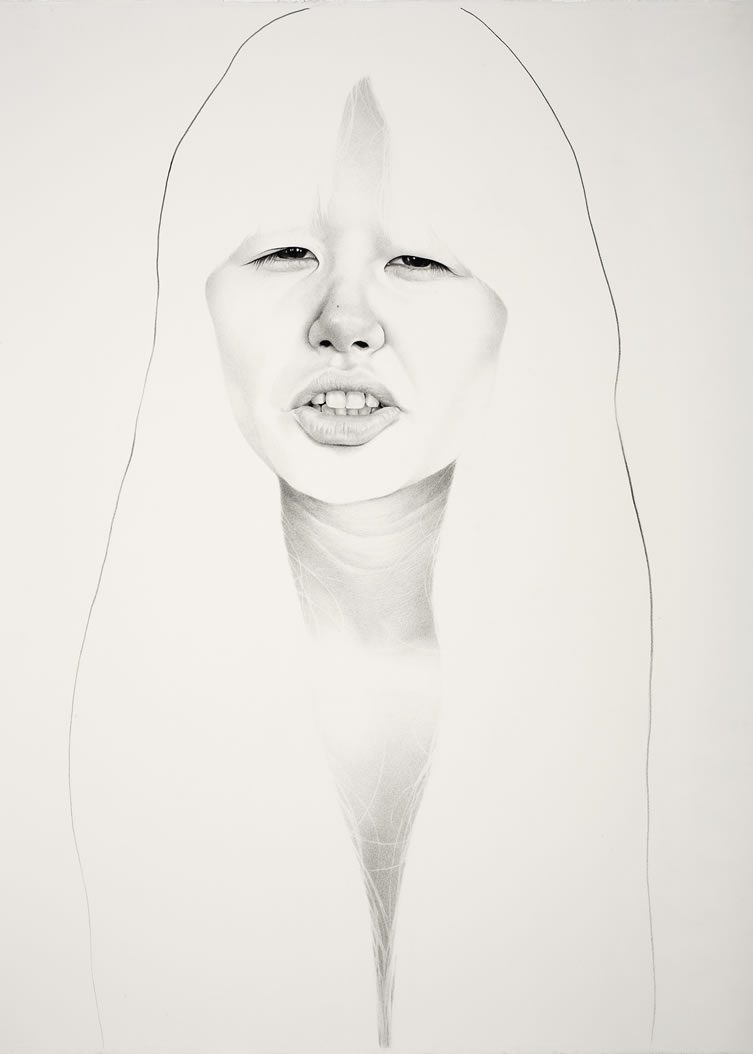

Sigourney,

graphite on paper,

30″ x 22″, 2013