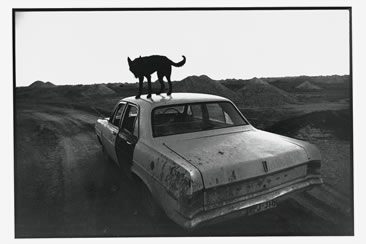

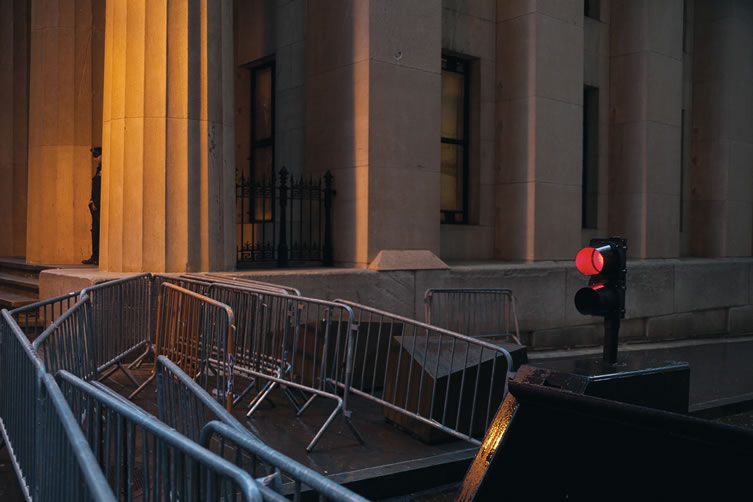

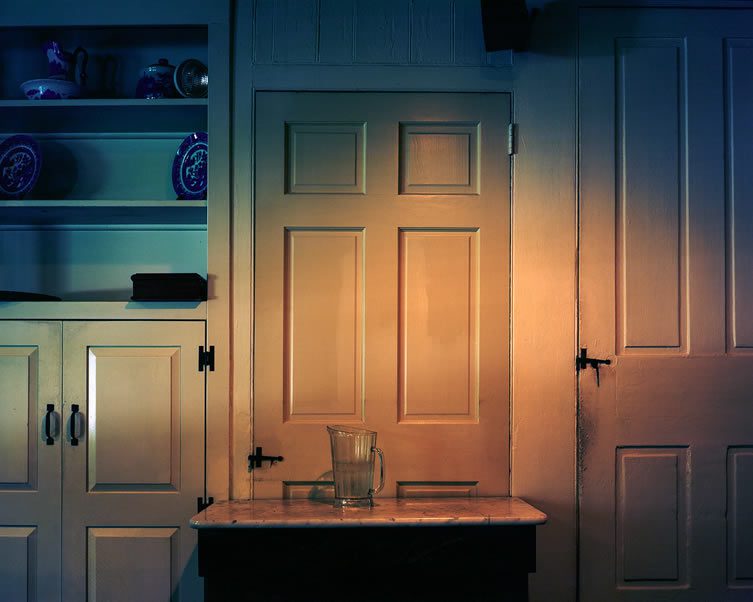

In one shot, barricades are scattered across a deserted downtown Manhattan street; in the background a policeman appears from behind a neoclassical pillar, hardly there but sinisterly there all the same. Turn the page and somebody — a threat? we, the audience? are we a threat? — is looking through a gloaming tangle of winter branches at a weather-boarded eastern seaboard house. In another, a tiled floor is scattered with cheerios. Another shows the deserted lobby of an office-building, where a TV presents President Obama saying – something.

Disquiet

These are all photographs from Amani Willett’s stunning collection Disquiet, and as the above will have made clear the connections, though undeniably present, are not always easy to discern. When I ask Willett about what ties them all together, the answer encompasses new fatherhood, Occupy Wall Street and the formal art of photography.

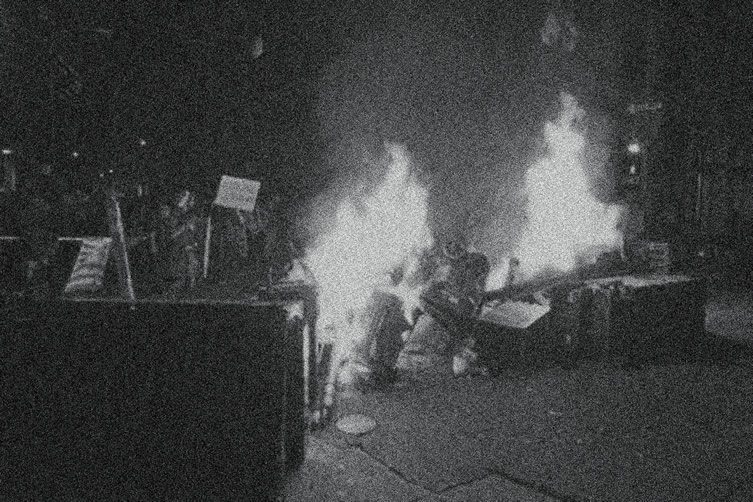

‘Part of what accounts for the variety of imagery in Disquiet is that the pictures were made from a very emotional place. I had a new family at the time — early 2010 — and I was focusing on making pictures of my family. When Occupy Wall Street happened, it cemented a lot the abstract thoughts I was already having about the state of the country. I was concerned about the world I was bringing my son into and OWS synthesised many of those concerns into a social movement. I began to visit and then photograph the OWS protests in NYC. So during this time-period I was reacting to the world around me without trying to analyse what I was doing — essentially I was working on a project without knowing it, just intuitively shooting the things I found important.’

[Cont.]

Disquiet

The inchoate project turned out to be Disquiet, a collection that as he says ‘puts his family life in direct dialogue with what was happening in our country at the time.’ It’s a compelling collection even coming to it cold, but with his explanation in mind it takes on a numinous power. You start to notice resonances: the scattered cheerios on chequered tiles echoing the scattered barricades on paving, the amber light on a city pillar the same tone as that falling on the frontage of a house in the country. No matter how organic the creative process, surely that cohesiveness can’t be entirely coincidental?

Disquiet

‘No,’ he says, ‘of course there’s a point at which I realised that it was a single, unified project. After I understood the direction I wanted to take the work, I started becoming more deliberate with the pictures I was creating — I knew what sort of images I still needed to make in order to finish the project.’

That extended particularly to formal concerns.

‘The first images I made for Disquiet had a particular formal sensibility about them. They were dark and often lit with warm light from a single source. As I continued to shoot, I was very conscious of the color story I was creating. And when it came time to lay out and sequence the book, one of the biggest considerations was how the formal aspects of the images helped to propel the story I wanted to tell.’

[Cont.]

“Hiding Place,” Cambridge, MA,

The Underground Railroad

“Bowen’s Basement,” Cambridge, MA,

The Underground Railroad

“Vicker’s Tavern,” Exton, PA,

The Underground Railroad

Disquiet

Willett seems mildly surprised when I point out that there is something distinctly and particularly ‘American’ about the work. There is, though, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that he took a BA in American Studies at Wesleyan University before moving on to New York to study photography.

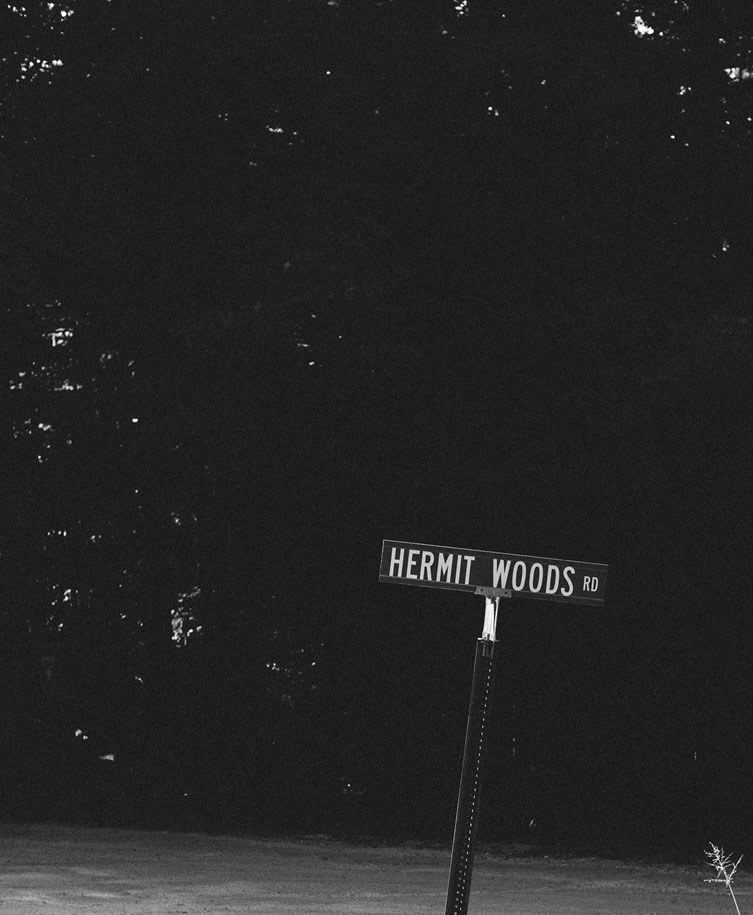

The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer

‘Y’know,’ he says, ‘I’ve never though of my work as being particularly American, but you’re right — it most definitely is. Both sides of my family have been in this country for hundreds of years, so it would make sense that the projects I pursue are about a particularly American experience. Disquiet looks at my family’s life within the context of the world we were inhabiting in 2010 and The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer also uses a similar strategy by looking at the life of a hermit in New Hampshire at the end of the 19th century. And The Underground Railroad looks at ideas of history and memory.’

It’s not an uncomplicated relationship, however, that he has with the country.

‘There’s something that may seen unrelated here, but in fact it’s central to my identity and who I am as am artist, which is that I’m interracial — my mother’s black and my father white, and growing up in the ‘70s and ‘80s it was not as common as it is now. Throughout my childhood people would ask “are you black or are you white?” and it was never a question I was comfortable with, as I saw myself as a combination of both of my parent’s backgrounds and embraced that identity. I think being interracial and not looking black or white made a lot of people uncomfortable. People didn’t and often still don’t deal well with ambiguity, but I embrace it. I feel much more comfortable living with complexity than reducing or simplifying.’

[Cont.]

Disquiet

That ambiguity, that fascination and ambivalence, is present throughout Willett’s work, from The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer, a kind of photodocumentary exploring the life and legend of a nineteenth century New Hampshire Thoreau-like recluse, to The Underground Railroad, which takes a not dissimilar approach, testifying in unexpected details to the story of escaping slaves and those who helped them. If that all seems rather on the heavy side, though, it’s worth remembering that Willett can turn his eye and interests to more whimsical ends. I’m keen to talk a little bit about that before our conversation comes to an end, and On Display is a perfect example.

On Display

‘The way On Display came about was that, while shopping for a new phone, I noticed other customers had been snapping selfies and leaving them on the devices. Without really thinking much about it, I began taking pictures of the cell store selfies with my own phone, and then at home I cropped everything out of the frame except the faces. I was amazed by what I saw in the resulting images, which were portraits with remarkable intimacy, humor and sadness. Anyways, over the next year (up to the present, in fact) I just continued, and now I’ve got around 75 of the things.’

A fun and surprisingly moving collection, even it is not without an edge of anxiety (one of his digressions on the subject tackles Willett’s concern about privacy and people’s attitudes to their image in the age of social media, and the collection is partly motivated by his concern with diversity and racial identity in New York City), but what comes across more than anything is a poignant yet lighthearted humanity. In a sense, it provides a nice alternative route into thinking about Willett’s work in general. For all its formal riguor, careful composition and cultural seriousness, it is also defined by a lightness of touch and a spontaneity that brings his subjects to life in unmistakable and surprising ways. I can’t wait to see where he turns his eye next.

The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer

“Duffield Street,” Brooklyn NY,

The Underground Railroad