Sean Norvet is that rare — I would have said impossible — thing: a contemporary artist who seems to draw equally on Renaissance proto-surrealist Giuseppe Arcimboldo (he of the beautiful, horrific plant-people), on the exuberantly ribald cartoons of Robert Crumb and on the happy-go-lucky, barely cohesive LA of The Big Lebowski.

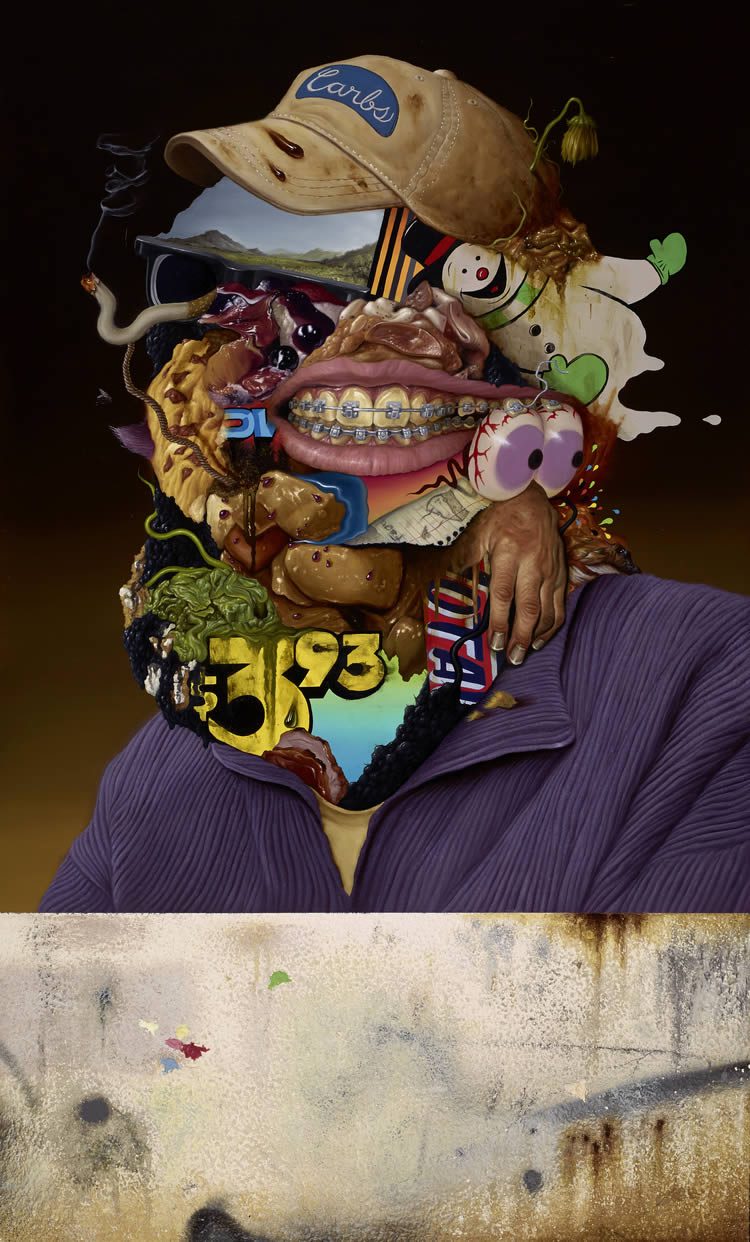

Impossible, you say? Just take a look at Locals Only or Mad Carbohydrates (Arcimboldo Takes a Trip to the Topanga Mall) and tell me I’m wrong. I start by asking about the seemingly unlikely Renaissance connection and it turns out Norvet’s a long-time Arcimboldo fan.

Mad Carbohydrates

(Arcimboldo takes a trip to the Topanga Mall), 2014

Oil, spackle & aerosol on panel. 36″ x 60″

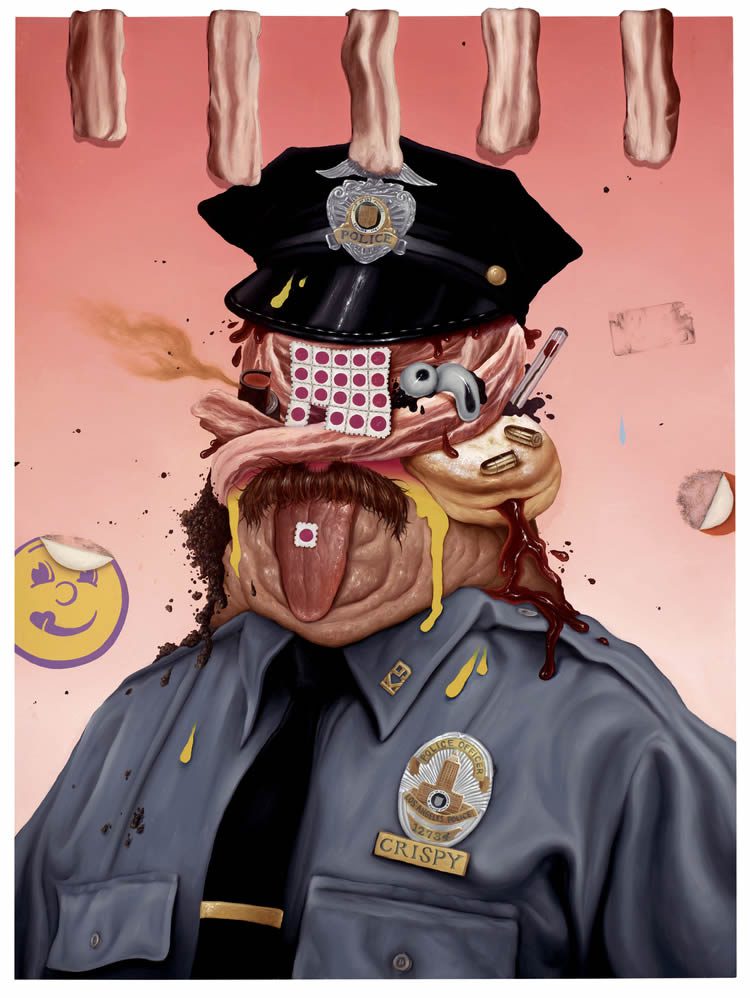

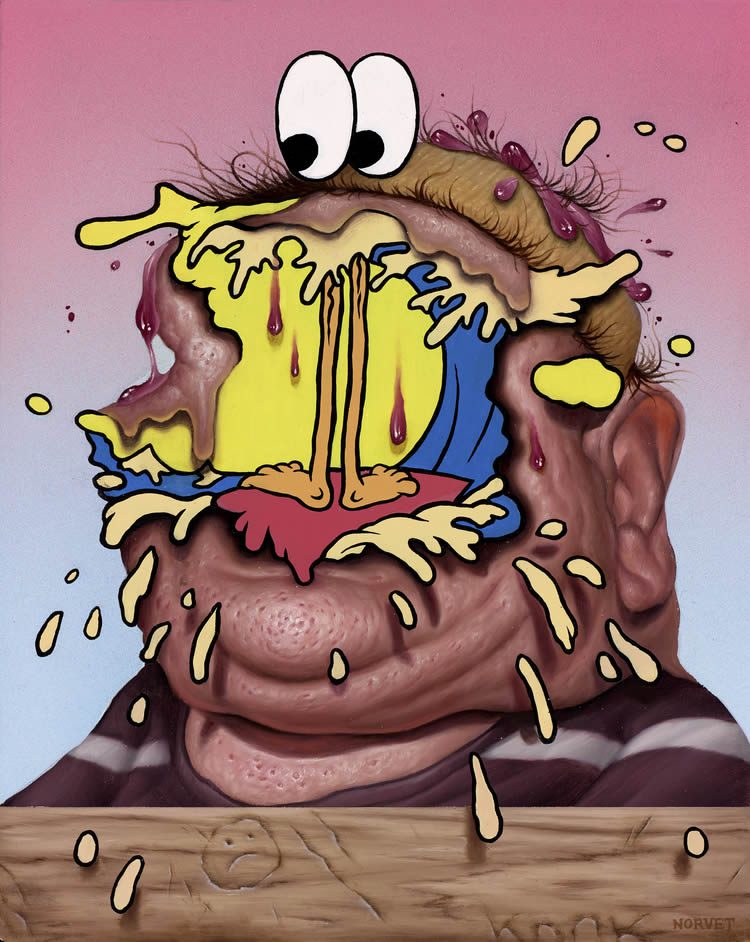

Fried Forever, 2015

Oil & Epoxy Putty on panel. 24″ x 18″

‘I remember seeing one of his portraits a while ago — I came to it cold with no idea who he was, but was an instant fan. I think what drew me to his work was how refreshing it was, the subtle humor of it. I’ve loved his work ever since.’

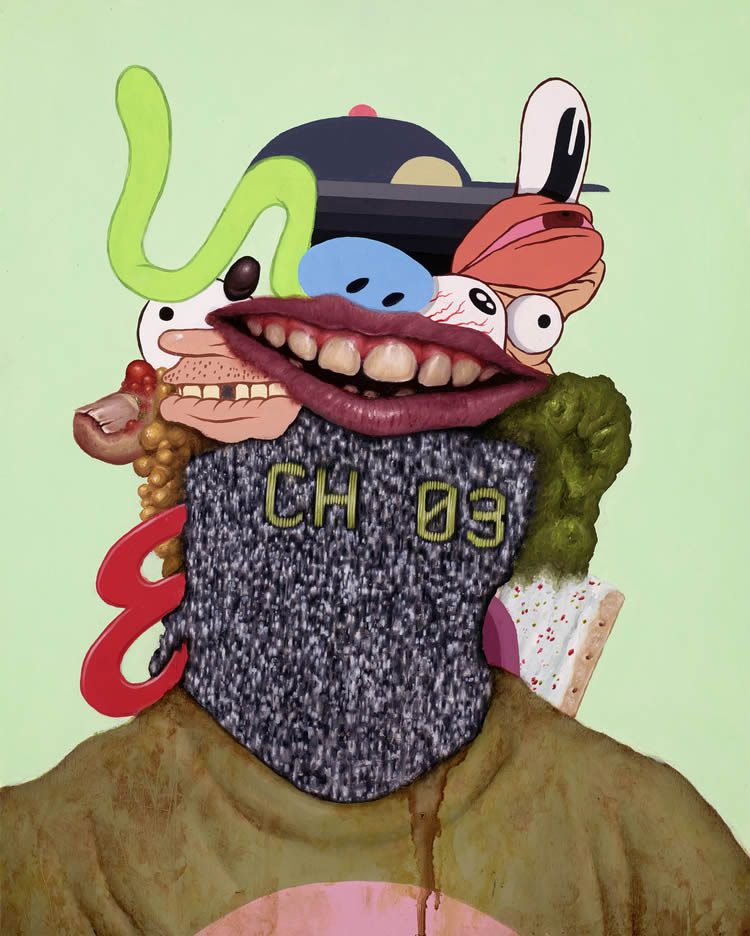

Arcade Face (Tilt), 2013

Oil & Acrylic on panel. 20″ x 16″

It’s obviously a major touchstone, but hardly the only one. Norvet’s work is a thing entirely of its own, violent and fun and affectionate and satirical. I ask him about that satirical element: it’s pretty ubiquitous to some degree or other, but a piece like Arcade Face (Tilt) seems like an unmistakeable and forceful piece of social commentary, a human made of cheap vices, bad skin and junk food. Fun as it is, it’s also pretty jaundiced.

‘I guess it’s more a case of casting a satirical eye on American culture than anything else,’ Norvet informs me, perhaps playing it a little (advisedly) safe. ‘I’m not trying to preach on what’s bad or good, I’m just inviting viewers in to enjoy and have some fun.’

The fun and affectionate side of the work is undeniable. For every example like the above there’s another whose sheer sense of exuberance and twisted joy pre-empts thinking about it too analytically. How did the style develop?

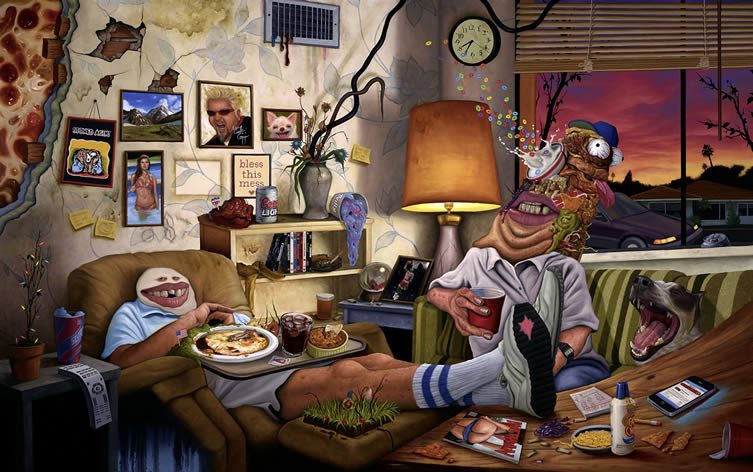

Waiting For The Pizza Delivery Man, 2014

Oil on panel. 60″ x 96″

Party Supplies, 2013

Oil on panel 20″ x 16″

Saturday Mornings, 2013

Oil & Acrylic on panel. 20″ x 16″

‘It really started to develop once I graduated art school. A lot of my early work started with attempts at distortion and warping of the human anatomy. I would stretch out body parts and push them around. I then became interested in surrounding figures with clutter-filled space (random objects, food, shapes etc). Eventually, the backgrounds and the figure switched places and I started mashing-up objects into the figures themselves. I started to become more fascinated by the everyday items that make us who we are than I was in the person’s actual appearance.

Norvet’s people, then, are half people and half environment. That makes the city and culture — landscape, cuisine, population, detritus — of LA a character in itself.

‘I was born and raised in the Los Angeles area,’ he says, ‘so it’s pretty much embedded in me. There’s no getting away from it. It’s everywhere in my imagination.’

Consciously? Does he deliberately pick icons and objects for effect, or does it all form itself organically? I’m interested partly because they are so coherent as single images yet are also clearly composites.

Smelt It. Dealt It.

Oil & Acrylic on panel. 20″ x 16″

Watermelon Sweater, 2016

Oil & acrylic on panel. 10″ x 8″

‘It really depends on the piece. They usually start with a main idea and the imagery coalesces around it naturally, so I normally approach a new painting pretty loose. Sometimes, though, I have a general theme that I’ll play off of. In either case, at certain points I can be, like, “What the fuck am I doing?”. It’s the best and worst part of the process for me. The spontaneity keeps it exciting, and the imagery, each individual component, is part of that process.’

The Thirst, 2015

Oil on paper. 15″ x 11″

I’m also interested in the tone. We’ve already talked about the fact that the work is everything from appealingly fun to repulsively ugly to aggressively parodic. What feelings is he really interested in provoking in the audience?

‘My main focus when creating is to make something that’s exciting and/or makes me laugh,’ comes the refreshingly simple response. ‘I guess my mood can come in and change things up a bit, but the main goal is to make work that makes me happy. It’s a pretty organic process, pretty unselfconscious. Usually the finished piece looks nothing like my first sketch/idea, so maybe I’m not even the best person to ask about the way the audience feels in the process of looking at it …’

That seems like a fitting (lack of) mission-statement. Satire shouldn’t need to be explained, and nor for that matter should fun or surrealism — that’s kind of the point of all of those things. So in that spirit perhaps we should simply let Sean Norvet’s burgers-with-teeth, people-made-of-burgers and coach-potato-turkeys alone and just enjoy them for the body-horror, pop-culture, LA good-time nightmares they are. Here’s to that.

Surf School, 2016

Oil & acrylic on panel. 10″ x 8″

Huy Fong, 2014

Oil on panel. 18″ x 12″