It’s 2012, and Enric Palau, co-founder of of Barcelona-based international electronic music behemoth Sónar, is — in an interview with Spin — rebuffing a criticism that has increasingly been levelled at the festival over recent years: their open-door policy to the odd act who upsets the apple cart among purists … namely the big stars of EDM.

Skrillex, Sónar 2015

‘Within 100 or 120 acts, to have one or two examples of what is happening in the world of electronic music that keep that younger public in mind, I think it’s justified.’ Explains the Catalan musician when prompted about Deadmau5’s inclusion on the prior year’s bill. ‘It’s important to us that the festival isn’t seen as a snobby kind of thing. Deadmau5 is as important as you make him.’ Quite.

Cynics form an orderly queue. Big names sell tickets, right? But then Palau moves on to a more valid point: ‘speaking with our friends in [Portuguese electronic act] Buraka Som Sistema recently, they said that if just 10% of this new public that’s going to the big American EDM events gets interested in discovering new sounds, that alone is positive.’ Breaking down barriers can, of course, have hugely favourable results. And, after all, wasn’t dance music founded on openness?

Kraftwerk, Sónar 2013

Communications director Georgia Taglietti adds weight to all of this, talking to Resident Advisor on the eve of their 20th anniversary the next year: ‘it’s important for us that people who like Skrillex, whose generation tends to be younger, can be present for a 3D concert with Kraftwerk. So they understand the roots.’ It’s a statement that continues on the thread of openness and exposure to new sounds; but also rooted in the deep-seated respect that runs through the electronic music community.

—

‘It’s important for us that people who like Skrillex can be present for a 3D concert with Kraftwerk. So they understand the roots.’

—

Sure, if you ever loved a guitar band you’ll have probably trawled back through the artists who informed them; if you like The Strokes you should dig Blondie, or Talking Heads; fans of Primal Scream should be fans of the Stones who should be fans of American roots music. But dance music denizens have a tradition of respecting roots that is altogether more religious. Detroit, Chicago, New York, London, Berlin. Atkins, Saunderson, May. I Feel Love, Autobahn. Knowing your Arthur Russell from your Arthur Baker.

SonarVillage

That pioneers are never forgotten is of huge importance to club music and the people who shape it; and that the big wheels of EDM oft fail to uphold this tradition is a familiar gripe. It is bold of a festival that holds experimentalism, innovation, and roots as core values to dally with these controversial names like so — wouldn’t it be easier to just avoid blokes with massive Mickey Mouse heads who confuse their 5’s with their s’s? To understand what shapes a train of thought like this, we need to head back 23 years.

Sónar 1994

It’s 1994 and the internet barely exists. Remember CD-ROMs? Car phones were still more popular than mobiles, which could then double up as dumbbells. The PlayStation was launched. Tapes — video, and audio — were still very much a thing. And the aforementioned Enric Palau, along with friends Sergio Caballero (visual artist and musician), and Ricard Robles (music journalist) founded a forward-thinking music and technology event that would come to rival Antoni Gaudí as the Catalan capital’s most famous cultural offspring.

Unlike the internet, electronic music was in full swing in the mid-1990s; the aftermath of rave having left the ‘super club’ in its wake. DJs were already superstars, but the thriving club scene needed its Mecca — and, with that year’s Criminal Justice Bill giving coppers a free rein to basically welly the shit out of anyone trying to throw a party in the UK, it was left to three Catalans to give birth to the festival that now defines its genre. Big names like Laurent Garnier and Mixmaster Morris were in attendance, as were almost 6,000 revellers, who flocked to Barcelona’s CCCB (Sónar by Day) and the city’s famous Apolo nightclub (Sónar by Night) between 2—4 June.

Sónar 1996

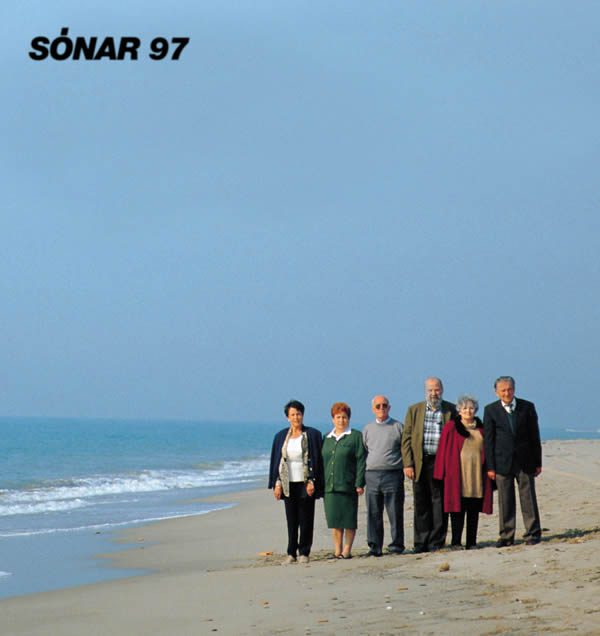

Sónar 1997

Sónar by Night would spend the next two years at a larger venue outside of Barcelona’s old town (the odd Disneyfied replica village, Poble Espanyol), whereas the day activities would remain in the heart of the city (adding neighbouring MACBA to its fold) until the festival’s 20th anniversary in 2013; when it would head out to Fira Montjuïc.

1995 saw visitors more than double, and big names like Orbital and Dreadzone were accompanied by multimedia installations and panels where those involved in the growth of the scene would discuss its past, present, and future. ‘Sónar is still only two years old,’ reads one prophetic archived review of the mid-decade edition, ‘who knows what it might grow up to be?’

Grow up it would. One of the festival’s defining moments would come in 1997, the tight-knit team (head of communications, Georgia Taglietti, joined the founding trio in the festival’s second year, and has been a key member since) booking one Daft Punk, at the height of their ascendency; a trick that wouldn’t be pulled off for the last time. That matter of roots and discovery would start to take shape here, too, Kraftwerk and Marc Almond counteracting rising names like Matthew Herbert and Chicks On Speed. In somewhat of a seminal year for the event, co-founder and artist Sergio Caballero would also take his visual concept for the festival in a progressive new direction.

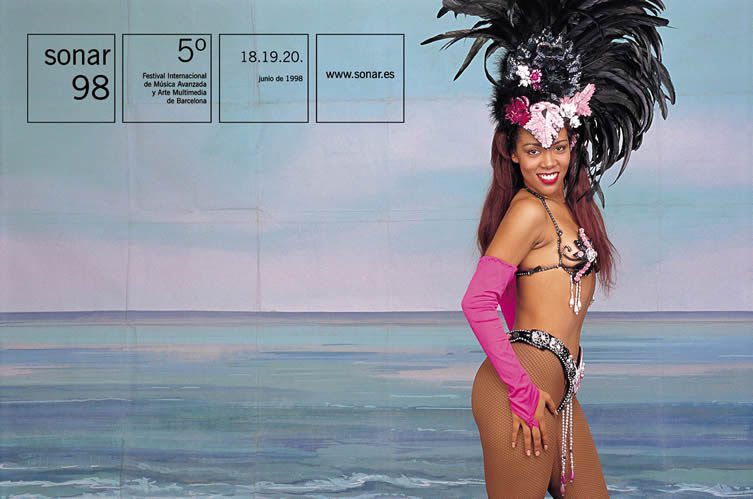

Sónar 1998

Sónar 2000

Sónar 1999

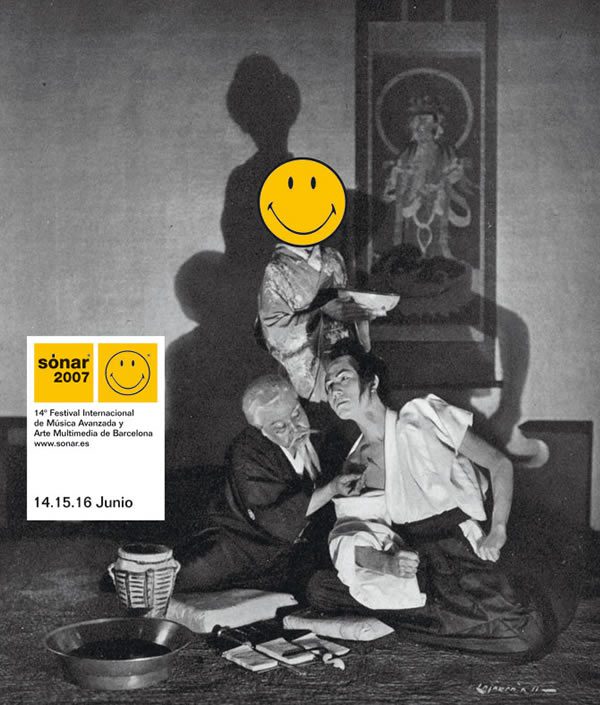

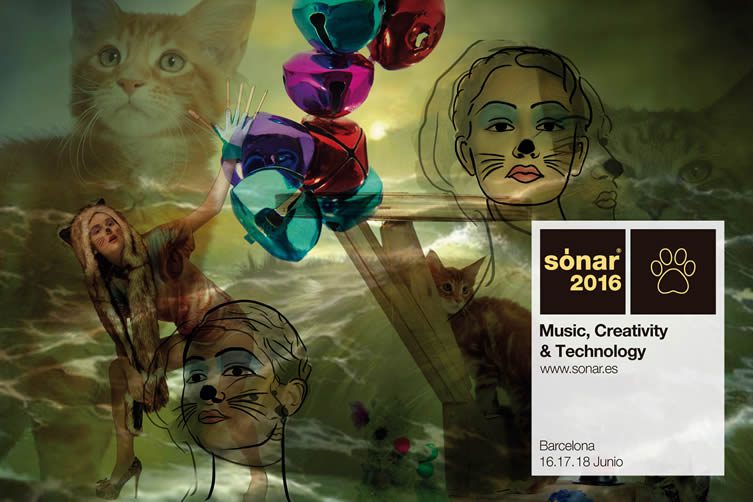

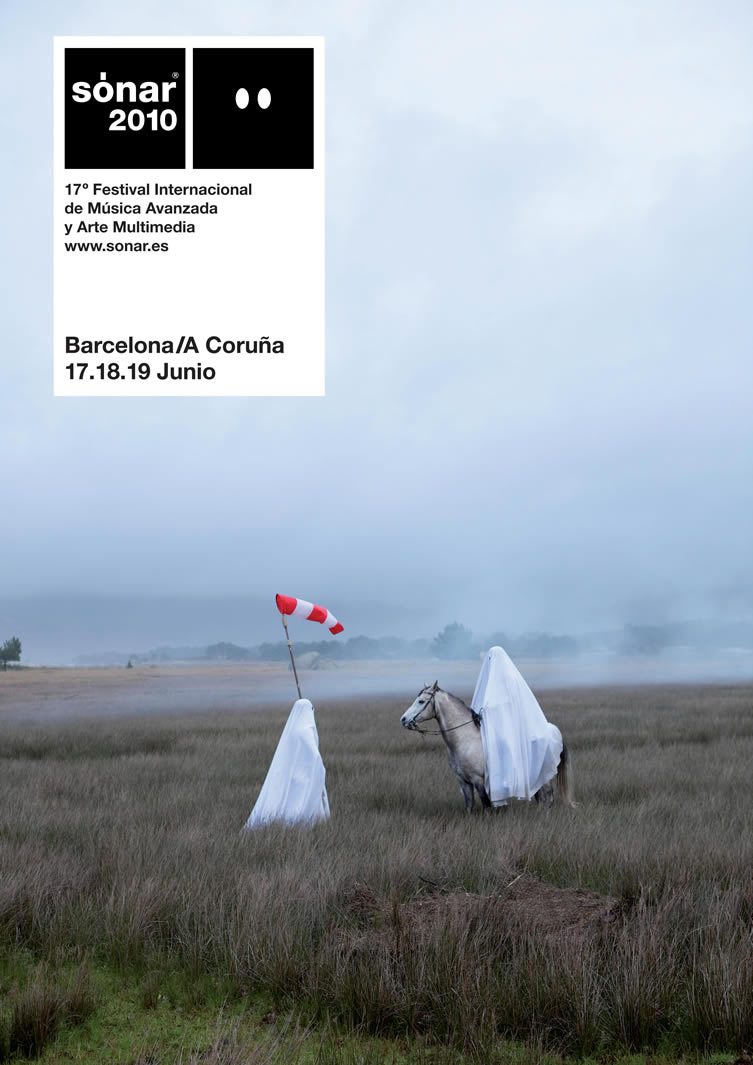

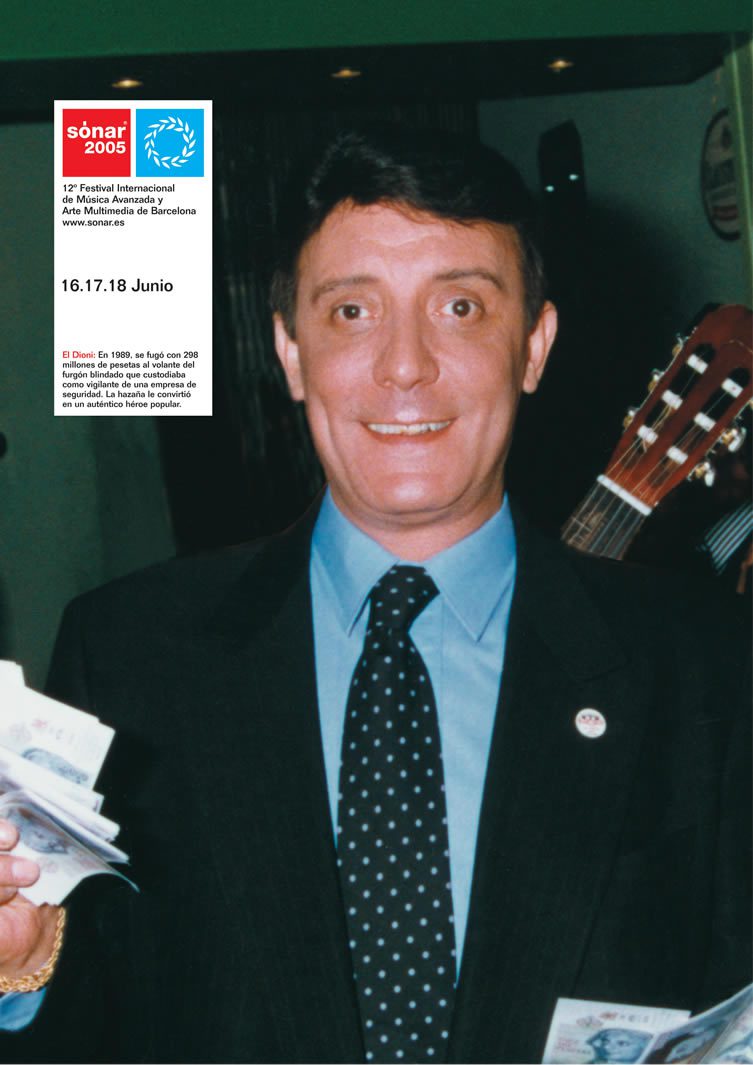

Until this point, the Sónar look had followed suit with similarly minded events around Europe. In 1997, the founder’s parents bafflingly took centre-stage; strolling on the beach, and enjoying a courtly glass of wine. Caballero is a radical thinker, and a key cog in the wheels that have led Sónar left-field; his unpredictable artistry has carved out an imitable identity for the festival.

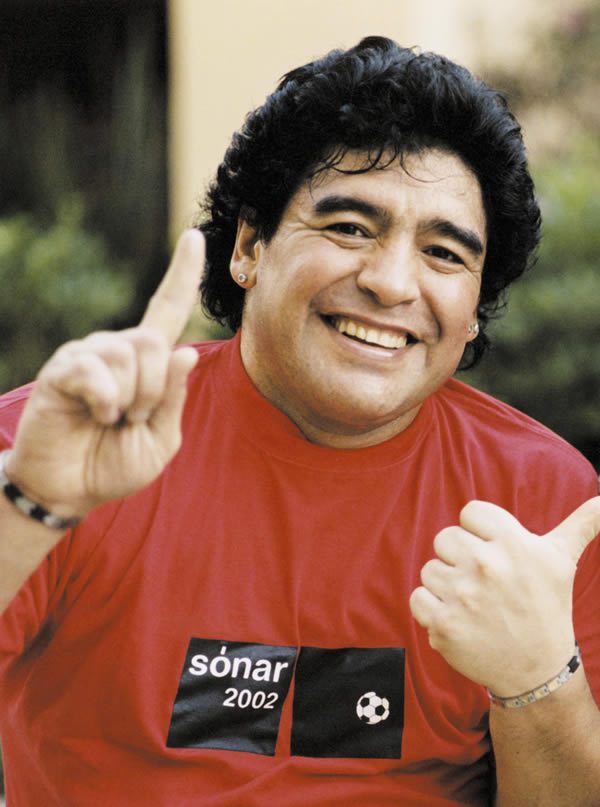

Sónar 2002

In what has become known as the SonarImage, the composer/artist/filmmaker conjures up a surrealist concept that comprises a wider campaign; posters, flyers, films (some of which would become fully fledged features, shown at film festivals around the world) … from bearded cheerleaders to a waxwork Elvis, dogs on wheels to supernatural twins, telepathic dwarves to Diego Maradona. They are ‘an image that has nothing to do with anything,’ he tells arts publication Studio International, ‘but that works and sells the festival, because we shouldn’t forget that we do have to sell tickets.’ Pragmatism in the midst of madness, God love a rebel with a cause.

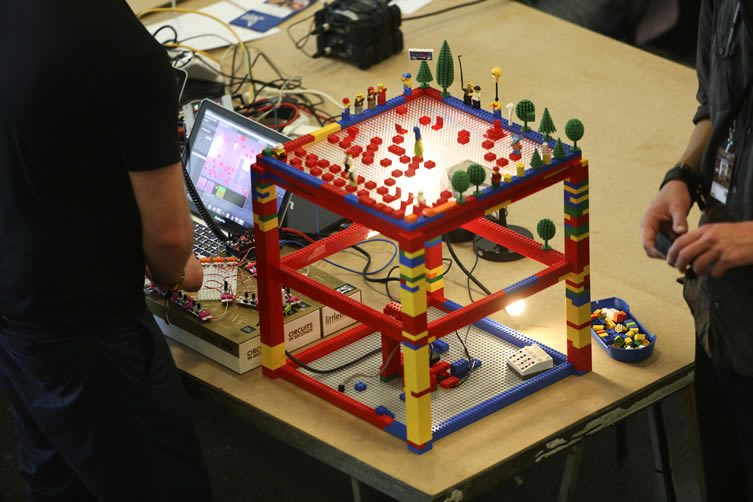

Caballero’s offbeat work cuts deep against the grain, it is atypical, arcane, and it typifies the Sónar experience; ‘I’m interested in the creative process. I couldn’t care less about the final work,’ he declares — and, in a way, that anarchic standpoint can characterise the festival as a whole. Much of what makes Sónar is process. What began as an accompanying record and technology fair would become SonarPro — which in turn would become Sónar+D in 2013 — a major culture and tech congress that now sees talks, workshops, exhibitions of brand new technologies, installations, performances, and all manner more running in tandem with the three days of music.

Sónar+D

2016’s Sónar+D will see chin-stroking topics like ‘the impact of algorithms on cultural tastemaking’ and ‘the potential of data to become the raw material for artistic creation’ being mulled over; icons like Jean-Michel Jarre and dubstep pioneer Kode9 talking about their work; folk from ALMA, the world largest astronomical observatory, will muse on the relationships between art and science; there’ll be major immersive installations by British studio Semiconductor, and New York artist Tristan Perich; and Mr Brian Eno will host its inaugural conference. Which, frankly, doesn’t scratch the surface of what over 4,500 professionals from 50 countries will take part in — it’s all much, much more than simply a sideshow.

ALMA, the world largest laboratory

Back, though, to what now brings well over 100,000 into the Catalan capital each June. Occupying the Mar Bella sports pavilion for four years from the pivotal 1997 edition, Sónar by Night was on the move again in 2001; settling into the same cavernous Fira Gran Via L’Hospitalet space that it occupies today. A series of hangar-sized halls that likely eclipse every other rave venue you’ve set foot in.

With a main ‘room’ (SonarClub) that can hold more than 15,000 — names like Beastie Boys, Björk, Massive Attack, and LCD Soundsystem have been accompanied by a who’s who of electronic music across the venue’s trio of other stages. The Sónar set-up that we see today was completed with that 2013 move for Sónar by Day from its spiritual home in El Raval’s cultural nucleus of the CCCB and MACBA.

Sónar 2000

Sónar 2001

Sónar 2004

Sónar 2008

Sónar 2013

You may think it hard to retain relevance through such exponential growth, that the off- movement (a series of events that have become a serious fringe concern) and the countless other parties that spring up in the city every June would detract from the doddery old dinosaur. But let’s briefly go back to our friend Sergio Caballero: exploring themes of sacrifice in the 1980s with Los Rinos (the art collective he had formed with two pals as a teenager), the trio would produce Rinosacrifici — a piece of video art performance where one would decapitate a pigeon with his penis.

‘We’re now living in an era that’s way more fascist when it comes to censorship,’ he laments in that Studio International interview, almost indignant that anyone should turn their noses up at using your knob to decapitate anything. How very dare they. Oh, relevance … forgive the distraction, but, can you see a festival co-founded by a man like this losing its experimental edge?

‘I believe that over the past 20 years, Sónar has become a prescription brand,’ articulates Ventura Barba (executive director of Advanced Music, the company behind Sónar and Sónar+D), ‘so people trust our judgment, and some people just come here to discover new acts. That is the beauty of it.’ Which is true, as even those heralded for their encyclopaedic knowledge of avant garde music admit. I give you the late, great John Peel: ‘the great beauty of Sónar is that you can go along and you can hear music that you can’t hear anywhere else on earth, from countries that you never imagined even made music of that calibre.’

—

‘The great beauty of Sónar is that you can go along and you can hear music that you can’t hear anywhere else on earth.’ — John Peel

—

An impressive accolade for the small team. ‘The music program is based on a huge network that we have built over the years,’ adds Taglietti, ‘it’s built not only by us as artistic directors, but also label friends, artists, and journalists, who work together and give us their thoughts on what is coming out. It is based on a lot of work together, especially on behalf of Enric, who is the director of the booking department. He listens to proposals and puts together a puzzle that makes the festival work.’

Evian Christ, Sónar 2015

Indeed, last year’s edition felt as fresh as a naked stroll on a glacier. The sun-drenched SonarVillage saw crowd-pleasers like Hot Chip, Kindness, and the irresistible hedonism of party DJ Nick Hook (who led the crowd out of the day venue by marching brass band) holding court, indoors that renowned ability to catch its audience off balance was as acute as it has ever been; perplexing Venezuelan producer Arca collaborating with video artist Jesse Kanda on an uncompromising performance, Evian Christ’s punishing set of disorientating beats and visuals, Bristolian Sebastian Gainsborough (aka Vessel) ushering in an aural apocalypse. Cut Sónar open and it bleeds its core values: introduce new music, keep roots alive.

Kindness, SonarVillage 2015

If Arthur Baker (not Russell) was the roots behind Hot Chip, Autechre would be the roots behind the exploratory sounds indoors — the former kept SonarVillage dancing to an impeccable set of vinyl and 808, the latter bringing disorder to SonarHall with unflinching rave music thundering from complete darkness, the Rochdale duo eschewing fancy visuals in favour of a bleak absence of light. These stark contrasts, bold juxtapositions, are the quintessence of Sónar and — as the festival prepares for its 23rd annual meeting — they show no sign of abating any time soon.

Which should bring us to a close. A neat loop in the story of a festival that revels in doing things its own way; who don’t really care if you don’t like Deadmau5, who think it’s important that Skrillex fans understand the significance of Kraftwerk, and who regularly confound with artists you’ve never, ever heard of. But it is not. What do Reykjavík, São Paulo, Chicago, or Tokyo, have in common? Our friends from Barcelona, that is what.

Sónar Stockholm

‘Even though Sónar Barcelona has been and will always be our flagship property, we are developing an ecosystem of festivals around the world,’ Barba tells me. He’s right; since 2002, Sónar has held an impressive 53 festivals around the world.

Sónar Reykjavík

London; Buenos Aires; New York; Santiago de Chile; Hamburg; Rome; Lisbon; Boston; Bogotá; Seoul … such is the appetite for the house that Palau, Robles, and Caballero built (visitors from over 90 nations flock to the Barcelona edition each June), that Sónar’s touring celebration of creativity and technology has become a critical constituent of the brand as a whole.

It goes back, in part, to what the legendary Mr Peel had to say about ‘countries that you never imagined even made music of that calibre,’ and Barba confirms it: ‘in fact, one the objectives of Sónar has always been discovering and connecting different artistic communities around the world. We aim that every single local Sónar is perceived as a tool for the local creative community, a tool to express their work and a tool to promote their work through the Sónar ecosystem. Hence each international Sónar has its local flavour.’ Which circles back to everything we’ve heard about a festival intent on going about things its own way. And the way right now? Home. It is 22 days until the 23rd edition of Sónar Barcelona, what to expect?

ANOHNI

Kelela

ANOHNI, the artist formerly known as Antony Hegarty, will be swapping her Johnsons for Hudson Mohawke and Oneohtrix Point Never (collaborators on the singer’s potent new album HOPELESSNESS); rising stars like incredible U.S. r&b artist Kelela and grime’s newest star Stormzy; there’ll be good times in the sun with Spanish beat-smith El Guincho, and the off-kilter clattering of jazz/hip-hop live band Badbadnotgood; and those roots, in the shape of Jean-Michel Jarre, New Order, and Kenny Dope.

But please, if any of that whets your appetite, and it really should, do as John Peel did; as its founders intend. Move between spaces. Explore your own boundaries. Play around with technology you thought only musicians could touch. Talk to people. Experience something for the first time. Dance. Drink. Respect the artists who have shaped this beautiful scene. Lap up the daring of those who are reshaping it. Dance. Drink. If you can complete the first names of Atkins, Saunderson, May; if you know the difference between Arthurs Russell and Baker — or if you don’t — Sónar will be your map to a weekend of enlightenment. And it will be the uncompromising bastard who rips it up. The end.

Sónar 2010

Sónar 2005