It’s 10am on a September morning. We — a few journalists, some PR folk from Ballantine’s and photographer/filmmaker Dave Ma, the star of the show — are on a hill to the east of Inverness that looks down over Dufftown in the valley below (in its own words ‘The Whisky Capital of the World’).

We’re flying drones into unseasonably brilliant sunshine and mostly blusterless skies, taking pictures of the broad sweep of the hills and the scattered wind turbines and mostly deserted farmhouses dotted among them. Drams have already gone the way of all drams.

A digression. We are here, ostensibly, to learn about Ballantine’s, which if you’re a Briton you might be surprised to find out is the world’s second most popular Scotch (but just ask anyone from pretty well anywhere else). More specifically, we’re here to learn about its collaboration with Dave Ma for the limited edition Ballantine’s Artist Series gift-packs. True to off-topic form, though, I’m talking to Ma mostly about a small town near California’s Death Valley and the Soviet disaster-site Chernobyl.

In my defence I offer that there is more to this than unprofessionalism and a poor span of attention. Though known mostly for his music videos and band photography — he’s been Foals’ go-to filmmaker since long before they were festival headliners and has shot megastars including Nick Cave, A$AP Rocky and Skrillex — Ma also works on more idiosyncratic projects of his own. One of these is TRONA, a lyrical short depicting the lives of young people in the near-deserted eponymous California town. Above footage of younger denizens that’s at once desolate and poignantly sensuous, in voiceover an elderly man tells of a life spent there from his arrival decades before to the recent passing of his wife. It’s heartbreaking, I tell Ma, and he agrees.

TRONA

‘The music video I was in town for never ended up working out, but I was fascinated and haunted by the place anyway. Having ended up there by coincidence, I’d made a weird connection with Trona and I realised I wanted to tell the story of it, via lives that were beginning there and also of one that was — well, that was coming to an end. I interviewed various people but as soon as Bobby Chastein started into the story I knew this was it. In the end it was so perfect that I only had to edit for length and a few audio blips; I didn’t even change the order of anything he’d said. That’s his story almost exactly as he told it.’

Delphic, This Momentary

Ma’s got an eye for a location, then, both visually and emotionally. A more obviously dramatic locale played host to Ma’s shoot for Delphic’s This Momentary single: the Exclusion Zone around Chernobyl, Ukrainian site of the infamous Soviet nuclear disaster, to which Ma had heard many of the old residents were (illicitly) returning. Pitching off-brief, he persuaded the band and label that something strange and otherworldly would be a better fit for the song (its refrain is ‘let’s do something real’) than yet another video of a photogenic band performing live. They agreed, and the resulting video is an off-kilter wonder full of derelict schoolrooms, prepubescent girls singing uncannily along, the beautifully lined and inscrutable faces of the elderly, the threat of chained-up dogs and a horse bucking in haunting slow-mo. Not a photogenic band-member in sight.

This, along with a shared interest in late-‘90s Chicago post-rock, is what I end up chatting over with Ma on the hillside — but back to Ballantine’s, to which I promise there IS a connection. A brand synonymous with top-end blended Scotch all over the world, even if it hasn’t achieved quite that kind of household-name status at home, the Highlands origins of Ballantine’s are precisely what it wanted to emphasise in the Artist Series, through collaboration with artists of distinctive and unique vision. ‘The Ballantine’s Artist Series,’ their release proclaims, stressing the integrity angle, ‘champions unique individuals that “stay true” to their creative style, and Dave Ma is no exception.’

These are exactly the kinds of thing, of course, that are always said during branding exercises like this. But in this case the combination seems unusually apt. The project combines Ma’s keen interest in the distinct particularities of place — what they mean to people, what they do to people, what people do in them, how they’re perceived and experienced — with the heritage of the whisky itself. In fact, everyone involved seems genuinely passionate about what’s come of the collaboration, and none more so than Ma himself.

‘I was ultimately drawn to working with Ballantine’s,’ he’s said, ‘for the excitement of doing something completely different that would still represent my artistic style, and for the opportunity to shoot a really unique perspective of that awe-inspiring landscape.’ Accordingly, from the outset his approach was to defamiliarise the place, to try to alienate the landscape from the aesthetic usually applied to it.

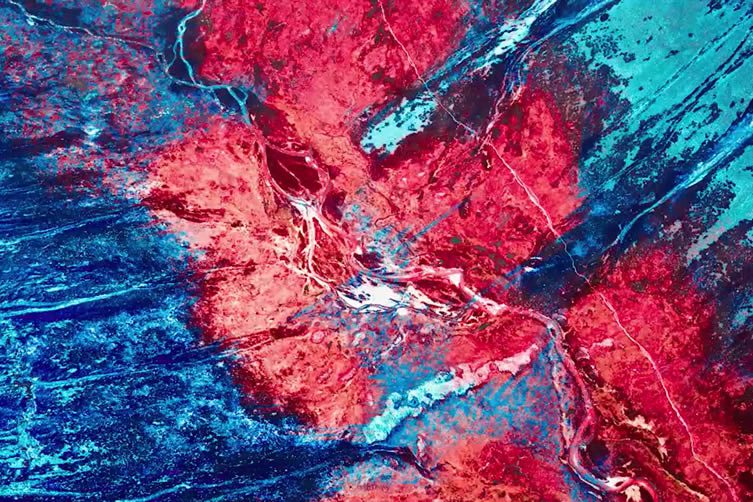

Rather than shoot conventional vistas of mountain and glen, tartan and bagpipe, Ma took to a helicopter and shot a series of aerial views of the expansive mountains and valleys surrounding Ballantine’s Highlands base. Then, in post-production, he wrought the images into a scheme of deep blues and vivid lava-reds that feels at once otherworldly — what planet are we even looking at? — and deeply sympathetic to the muscular, stormy topography. Finally, Ballantine’s took the images and used tactile printing technologies to really bring across their dramatically sensuous feel in a pair of editions of Ballantine’s Finest and Ballantine’s 12 Year Old.

The happy outcome of all this — selfish, but sue me — is that I end up talking the whole project over with Ma on a sunny hillside, sipping from a glass of the 12 Year Old and forming anew the strong opinion that a life spent in plush Scottish country piles being plied with fine victuals is very much the one for me. The evening finds us treated to music from remarkably accomplished young local folk musicians the Strathspey Fiddlers and, after a truly outstanding traditional Scots dinner of scallops, haggis and venison, enjoying (is ‘over-enjoying’ a phrase?) a range of Ballantine’s blends long into the early hours.

Standing outside as the moisture in the air starts to stiffen and chill — and this isn’t entirely the booze talking — I experience a moment of smug gladness that Ballantine’s felt the whole extravaganza necessary. The brand seems to be doing just fine on its own, as far as I can tell, and Ma’s career is clearly going great guns. But if they need artists like him — and, by extension, people like me — to reinforce their whisky’s connection to this remote and beautiful stretch of the world, then who am I to blow against the Highland breeze?