“The difference between technology and slavery,” writes Lebanese–American essayist, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, “is that slaves are fully aware that they are not free.”

Debt, social expectations, and the façade of democracy may have conditioned a sort of modern slavery, but a spiralling reliance upon technology is compounding it. This might sound like the melodramatic whine of a Westerner incapable of contemplating the worst this world has to offer, but there is a genuine darkness behind Silicon Valley’s brightly-lit screens. “I am convinced the devil lives in our phones and is wreaking havoc on our children,” says Athena Chavarria, a former executive assistant at Facebook now working with the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

The Catalan countryside at the beginning of November—when the sun still shines as the seasons shift. Where slow takes on a new meaning. A short train journey from the centre of Barcelona yet a million miles in state-of-mind.

Reports are rife that those closest to the technology are the ones most concerned—the child care contracts drawn up between Silicon Valley parents and their children’s nannies now routinely demand phones, tablets, computers, and televisions remain out of sight. With the average person today scrolling upwards of 20 miles per year, the reality that software designers are exploiting psychological vulnerabilities in the name of fostering addiction to their applications is dawning. Tristan Harris—an insider turned activist who wrote the essay The Slot Machine in Your Pocket—urges us to recognise that we are being persuaded by a system that is better at hijacking your instincts than you are controlling them.

“People often believe that other people can be persuaded,” he says, “but not me. I’m the smart one. It’s only those other people over there that can’t control their thoughts.” And like slot machines, this is an addiction that can ruin lives. With smartphone use and teenage depression rocketing in tandem, studies show that those spending five or more hours online each day were 71% more likely than those spending less than an hour to have at least one suicide risk factor (depression, contemplating suicide, making a plan or attempting). “On the scale between candy and crack cocaine, it’s closer to crack cocaine,” says Chris Anderson, former editor of Wired.

Which brings us to the Catalan countryside at the beginning of November—when the sun still shines as the seasons shift. Where slow takes on a new meaning. A short train journey from the centre of Barcelona yet a million miles in state-of-mind.

For the first time in history more people live in cities than in the country. As the Internet of Things dots the i’s and crosses the t’s on hyperconnectivity—microwaves and washing machines contributing to the Big Data profile of ourselves being built in the zeroes and ones that surround us—humankind is sharing boggling amounts of personal information. Some 2.5 quintillion bytes of data per day. There’s a palpable sense of this in cities. Cafés crammed with the glowing faces of remote workers, pavements gridlocked with senseless smartphone zombies. Here in Penedès all that stops. “No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality,” wrote Shirley Jackson. Technology’s exponential growth means our realities are shifting in front of our eyes. How long can we sanely exist?

Ignasi Romeu’s family have existed here for centuries—cultivating grapes and producing wine since 1730. The old winery having been abandoned for half a decade, in 2004 he and two friends opened the doors of Artcava; a low-key winery hand-producing a modest 18,000 bottles of chemical-free artisanal cava each year. Archaeological excavations at the family masia have shown that the Iberians were producing wine on the same site more than 2,500 years ago. Even in relation to the Romeu estate’s recent history, the explosion of home computing is a dot on its timeline—walking among the vines and muddying your pristine white sneakers, that reality begins to sink in. As someone who has experienced life both with and without the internet, it’s surprisingly easy to disconnect. How simple will that be for today’s generation?

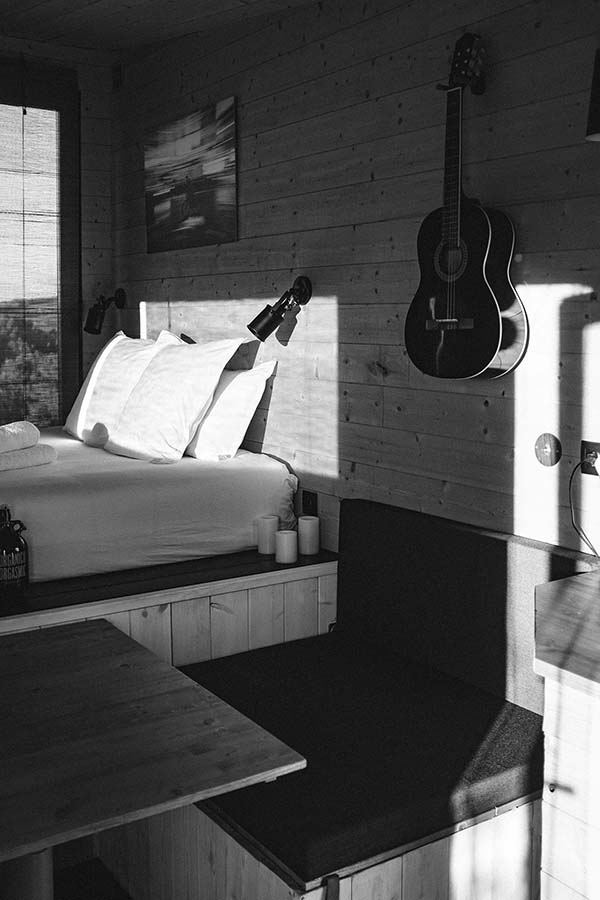

Perhaps that’s why there is a proliferation in experiences like this one. Here, on Ignasi’s family farmyard, sits what is universally regarded as a ‘tiny house’. Essentially a mountain cabin, Stendhal—surely named after the French author’s interest in individuality and the pursuit of happiness—is an eco-friendly, off-grid getaway that doesn’t just encourage disconnection, it imposes it. Placed here by tiny house startup Serena.House, the construction might be a no-cat-swinging-zone, yet no necessity has been overlooked. A cute solid fuel heater maintains a snugness as the cold country night sets in; a stove-top ‘moka pot’ and coffee grinder ensure morning caffeine fixes don’t go unchecked; guitar, books, and boardgames alleviate the boredom that arrives having disconnected from the attention economy; 100% solar-powered electricity enables a fridge to keep your cava cool. However, the most important consideration of this tiny house becomes clear as the sun rises the following morning.

If tiny houses are to iPhones what normal houses are to the carbuncle electromechanical mega-computers that debuted during World War II, then their beauty comes in mobility. And that means choosing your views. As dawn breaks, the humbling view of Catalunya’s Montserrat mountain rage reveals itself. Framed by the largest window of the cabin, its serrated peaks and imposing presence are as transfixing as the screens Tristan Harris is urging us to spend time away from. Yet this is one addiction free from consequence. “You get used to it,” says Ignasi of the view he lives with as he delivers a breakfast basket of homemade granola, jam and warm bread. Although you can tell he secretly hasn’t.

After breakfast there is nothing to do. Nothing. Just time to ponder the fact that the notion of ‘nothing’ has become steeped in negativity. It’s the hamster wheel world we occupy, where worth is measured by achievements. Nothing is to fail. It’s Silicon Valley’s culture of notifications reminding us to do something. Something, anything. But we do we gain from that something? “Doing nothing is better than being busy doing nothing,” said the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu. So often today we are all busy doing nothing. Here in the shadow of Montserrat, surrounded by vines, nothing takes on a new meaning. It’s a liberating experience.

Documenting a journey of spiritual discovery, Henry David Thoreau’s Walden was first published in 1854. Often cited as early inspiration for the tiny house movement, in it the transcendentalist chronicles the two years, two months, and two days he spent in a self-built cabin deep in the woodland of Concord, Massachusetts. “Why should we live with such hurry and waste of life?”

Back to the tiny house and dinner arrives in the same way as breakfast—a lovingly home-cooked three-course affair with warming soup and a delicious chicken casserole that sings with notes of cava.

He writes. “We are determined to be starved before we are hungry. Men say that a stitch in time saves nine, and so they take a thousand stitches today to save nine tomorrow.” The dogma of the capitalist West is to fixate on the future, to do something to avoid nothing. Thoreau—like Buddhist masters—learnt to live purely in the moment during his social experiment. Of course it’s a stretch to say you’ll achieve that here, but if even for a few hours, enjoy the silence and live in the now.

Truth is, this is entry level escapism, but any opportunity to reclaim your own inner peace in a world of purposeful distractions is golden. Ignasi stirs us from our solitude for a tour of the winery. It’s easy to see why Artcava receives such rave reviews—it is personable and absorbing. Discovering thousands of years of history, corking and labelling our own bottles, sitting down to sample the goods. There’s none of the hurry Thoreau would scorn. Back to the tiny house and dinner arrives in the same way as breakfast—a lovingly home-cooked three-course affair with warming soup and a delicious chicken casserole that sings with notes of cava. Like everything here there’s a sense of time and thoughtfulness, it’s a detail that heightens the experience and serves as icing on the cake for our final night spent alone in the middle of a vineyard.

Ignasi and his partners understand the concept of slow travel, Serena.House’s principles are the perfect match. In just a couple of nights you can feel a tangible reconnection to nature by experiencing an essential disconnection. Turn off, tune out.

Serena.House Barcelona Tiny House Photography © We Heart