Considered one of the first buildings of the Art Nouveau movement, Casa Vicens was also the first house designed by a certain Antoni Gaudí. Located in the Barcelona neighbourhood of Gràcia, brick and tile factory owner, Manuel Vicens i Montaner, commissioned the house. It also kickstarted the Modernisme architecture movement.

Art Nouveau was mostly prominent between 1890 and 1910 in France and Belgium. And this movement shared much with what the Catalans would call Modernisme. The movement embraced architecture, arts and literature. It was a coming together of creativity and culture, often grouped under the term fin de siècle (end of the century).

Fin de siècle would take many forms across Europe. Sezession in Austria-Hungary. Liberty style in Italy. And Modern, or Glasgow Style, in Scotland. Whatever they called it, the style was expressive and informed by nature in its most lavish forms. Decorative arts were undeniably taken to sumptuously ornate new heights by this movement. And, significantly, its legacy lasts to this day.

Casa Vicens is Gaudí’s first building in Barcelona. It became one of the first examples of the new movement in art and architecture that was taking place all around Europe in the late 19th century. The bold style was dubbed Modernisme in Catalonia.

Located in the middle of Passeig de Gracia, the building owned by Josep Batlló today attracts hoards of tourists. They vie for photos of its arched roof (which some say resembles a dragon), aquatic interiors and eye-catching façade; a colourful mosaic made of broken ceramic tiles.

Barcelona, the capital of Modernisme architecture

With over 30 Modernista buildings in the city, Barcelona is understandably the international focal point for this elaborate arts movement. Gaudí’s mixture of styles, materials and shapes are apparent in many of them.

There’s the world-famous: the sprawling Sagrada Família, remaining unfinished despite construction beginning in 1882, and several awe-inspiring structures within Park Güell. There’s even the surprisingly conventional. Casa Calvet, completed in 1900 for a textile manufacturer is ‘quiet’ compared to much of his other work. But no other building embodies his creative vision like Casa Batlló.

The Modernisme architecture icon can be found in the middle of Passeig de Gracia, an area linked to prestige and wealth in the early 20th century. Josep Batlló commissioned the building, and today attracts hoards of tourists, vying for photos of its arched roof (which some say resembles a dragon), undulating form, aquatic interiors and eye-catching façade; a colourful mosaic made of broken ceramic tiles.

Many consider the home a masterpiece, for good reason. It is Modernisme in its purest sense, barely a straight line with unusual ornamental embellishments, irregular oval windows, and flowing sculpted stonework.

Otto Wagner’s Majolikahaus in Vienna.

A style of flamboyance

It is this excess of ornamentation and lust for curves and rounded forms that characterise the style at large, each of the architects involved adding their signature style into the mix.

For example, French architect Hector Guimard, known for his Paris Metro entrances. Vienna’s Otto Wagner, whose apartment building Majolikahaus is famous for its many floral motifs. Or Glasgow-born polymath Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Flamboyance was en vogue, and an army of creative talents were shaping the turn of the 20th century. Let’s have a look at some of the Catalan movement’s other stars…

The Palau de la Música Catalana is a concert hall that combines elements of traditional Spanish and Arabic architecture. Designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner and built between 1905 and 1908, the building underwent extensive restoration in recent years. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

A complex built between 1901 and 1930, Hospital de Sant Pau was, incredibly, fully functioning until June 2009. The hospital underwent restoration for use as a museum and cultural centre recently. In 1913, Domènech i Montaner’s masterpiece received an award for the best building of the year from the Barcelona City Council. Photo © David Cardelús

Lluís Domènech i Montaner

Firstly, Lluís Domènech i Montaner. A Catalan politician and architect, he was another figure highly influential in the Modernisme architecture movement. Buildings like Hospital de Sant Pau and Palau de la Música Catalana are now designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

A mixture between rationalism and fabulous ornamentation, inspired by Spanish-Arabic architecture, each follow the curvilinear design typical of Art Nouveau. Their resplendent interiors and obsessive attention to detail are a thing of bombastic beauty. His work represents some of Barcelona’s most beautiful buildings.

Puig i Cadafalch’s Casa Amatller combines the neo-Gothic style with a ridged façade inspired by houses of the Netherlands. It is part of the renowned Illa de la Discòrdia, markedly one of Barcelona’s most famous blocks. The architect worked with some of the top artists and craftsmen of Barcelona’s Modersnista era, headed by sculptors Eusebi Arnau and Alfons Jujol.

Formerly a textile factory, architect Josep Puig i Cadafalch completed Fàbrica Casaramona in 1911. Having undergone many changes, it opened its doors as CaixaForum Barcelona in 2002. It is now an art gallery in the Montjuïc area hosting exhibitions sponsored by Barcelona bank, la Caixa.

Josep Puig i Cadafalch

Secondly, Josep Puig i Cadafalch. He was the architect of Casa Amatller, originally designed as a residence for chocolatier Antoni Amatller, and constructed between 1898 and 1900. Puig i Cadafalch may have had a style that separated him significantly from Gaudí, however, it’s this building (along with Casa Batlló and Domènech i Montaner’s, Casa Lleó-Morera) that makes up the three most important to reside on Barcelona’s famous Illa de la Discòrdia (Block of Discord).

This inimitable block possesses buildings by four of the most important Modernista architects. In the heart of the city, it famously confirms the fin de siècle movement in Barcelona. It is also one of the Catalan capital’s most photographed blocks.

Puig i Cadafalch also designed Casa de les Punxes as a home for the three daughters of textile industrialist Bartomeu Terradas i Mont. Reminiscent of old medieval castles and featuring six pointed towers crowned by conical spikes, the emblematic building dominates an intersection between three streets in the city’s Eixample area.

With a roof space of 600 m2, Casa de les Punxes is now home to live music musings during Barcelona’s warm summer. Futhermore, it is now home to coworking space, Cloudworks.

A similarly and emphatically underrated gem is Fàbrica Casaramona. The building was originally commissioned as a textile factory and eventually completed by the architect in 1911. The building has undergone many changes but opened its doors as CaixaForum Barcelona in 2002. The cultural venue in the Montjuïc area hosts exhibitions, concerts, and film screenings.

Gaudi’s unfinished La Sagrada Familia, finally nearing completion. Photo, alevision.co

End of an era

The Gaudi biography comes to an abrupt end in 1926, when the revered architect would die three days after being hit by a tram. However, the career of Gaudí was immortalised. To this day architecture aficionados make the pilgrimage to the Catalan capital to bathe in the glorious madness of Modernisme architecture.

You can tick of Antoni’s icons and lesser-known surprises, as well as imposing gems by Josep Puig i Cadafalch, Lluís Domènech i Montaner and Enric Sagnier. However, devout Modernistas might want to head a little further for some of the scene’s most uncharted treasures.

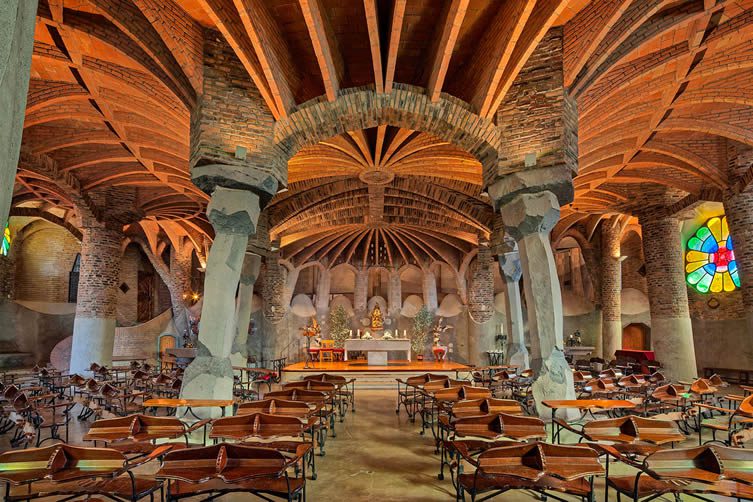

Gaudí’s Crypt at the Church of Colònia Güell. Photo © David Cardelús

Catalan Modernisme beyond Barcelona

Built as a place of worship for the people of Santa Coloma de Cervelló (less than 20 kilometres west of Barcelona), the Church of Colònia Güell is another work by Gaudí to remain incomplete. Due to Count Eusebi de Güell’s declining profits, the Catalan architect only ever finished work on a crypt. But that doesn’t make it less spectacular.

Here Antoni Gaudí would bring together all of his architectural innovations for the first time. Shifts in materiality and a fluid form would set the tone for his iconic Sagrada Familia.

A little further out of Barcelona, Gaudí would design a winery and several hunting pavilions on the Bodegas Güell complex in Garraf. Eusebi Güell has been blown away by his work at the Paris Expo four years prior (Güell’s more noted commissions for the Catalan would come in the same year).

Although the pavilions were never built, the winery, with a triangular frontal profile and almost vertical roofs, supplied wine to Cuba before ceasing due to lack of success. Nowadays, Bodegas Güell is home to the popular Gaudi Garraf Restaurant.

Gaudi’s El Capricho in Comillas. Photo, Pablo Ramos.

One of only a handful of buildings designed by Antoni Gaudí outside of Catalonia is El Capricho. Located in Comillas, Cantabria, it is one for the true devotees. Formerly a summer villa for Máximo Díaz de Quijano, the house is the jewels of European Modernism. These days it’s a cultural institution, open to the public and host to musical and theatrical events.

Lastly, situated in León, Casa Botines is a residential Modernist building designed by the architect, and pays homage to the city’s emblematic buildings.

Final Thoughts

Bold and brilliant, Modernisme architecture will continue to astound for centuries. When Sagrada Familia eventually finishes its build, or when someone restores another long-forgotten gem. Barcelona is home to much this movement’s icons, but the style has left a mark around the world. In dark and uncertain times, we should celebrate its message of beauty and positivity. Now more than ever we need architecture of whimsy and wonder. Dare to dream.

Barcelona is a destination for those seeking out this style. However, its message lies within us all. Be more. Be more bold, brave and audacious. Modernisme architecture represents idealist beliefs. Why can’t we seek idealism in modern times?