In art, inspiration comes from many places. Nature, love, trauma, the face you can’t forget. Look, see, make: the old one, two, three. For Jesse Leroy Smith – painter, curator and collaborator – the search for inspiration takes him one step further: making experiences in order to make art. Be it wearing a pumpkin head, buried overnight or showing the work of an invented artist, these experiences – otherworldly, ritualistic, outsider – are designed to feed his painting. Like a vampire feeding on his own blood.

But only partly, because as much as he likes to paint, Smith’s fascination with the old, the very rural, the lives of compulsive makers, comes from – and returns to – a love for being with people, people leading different lives, lives lived at the very edges of so-called normal living. Hence leaving London. Hence Cornwall. And hence a propensity for putting on shows that are as much about the experience of being at a show as they are the art being shown. Party on. Wildly.

A big fan of the naive, of making mistakes, of failure, Smith consistently, as artist, curator or collaborator, speaks in the voice of a specific type of community, one that is here and gone, a community of magic makers, a community that is ribald, staggering, drunk on itself, on oddness, on its ability to make things happen just because they should. In short, he’s the real deal, a rare bird. No doubt.

I believe you spent a night buried in your garden; and that a friend burnt a tree on top of your burial mound. What was that about?

Maybe to remember how it is to be 24. It started with a visit to an ancient underground city in Turkey, out of tourist season. A guard slept at the ticket kiosk amongst cans and cigs, so we sneaked past and I went down 9 storeys. But the lights went out – the guard must have woken up – and after the initial wonder at absolute darkness and silence, I panicked as I couldn’t find my way out. After much clawing, I shot out of there. The surface of the earth was bleached in light and life. I felt completely alive.

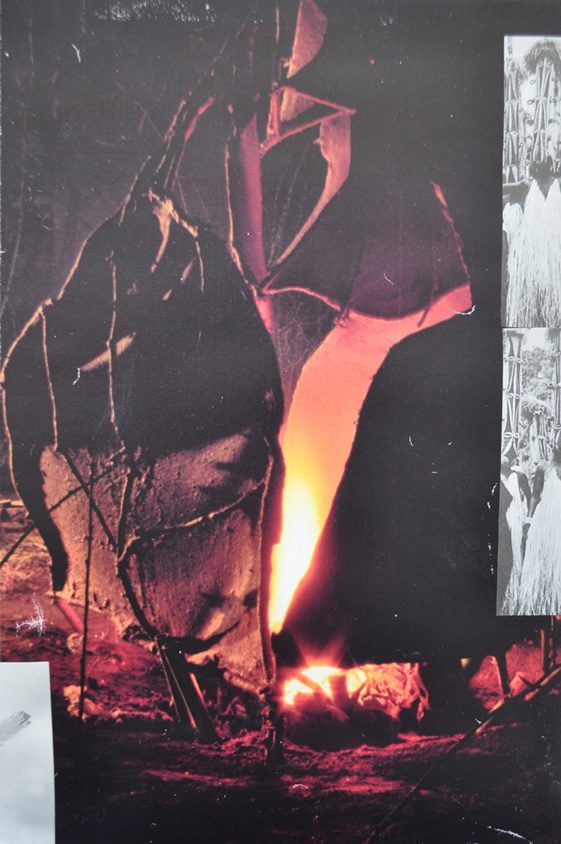

When I returned to London, I worked in my garden and local forest using fire, earth, glass, debris and such like. I had always painted, but this seemed the best way to explore my travel experiences. I made a kind of open den. I had a dream that I was underneath this plot. I decided to re-enact the dream. So, after going through about 2 ft of black earth, I dug a telephone box size hole, braced and carefully carved into the sand earth. There had been a storm. A cherry tree had fallen. I piled it up – from logs to twigs, as you sometimes see in mountains shacks. You can get a lot of joy from such things. I built a kind of tent from the branches to surround the hole.

That night, I climbed in. A friend lowered a trapdoor and the 2ft of black earth. He then burnt the wood over the night. At dawn, light came down the scaffold poles that I used to breathe. When all the wood was burnt he swept up the ash and dug me out. The January earth was steaming. We set fire to the tent and drank the last of the brandy.

Why did I do it? To me it was a lot about the absolute trust I had in my friend. Christ’s mates fell asleep. Mine didn’t. He was a great friend, but I don’t know where he is now.

Burial

A great deal of your life as a working artist was – and still is – spent in Cornwall. The place is positively jumping with painters, sculptors and the like. What is it about Cornwall that so get’s artists going?

It’s like an island in many ways, with such varied coastline. The further west you go, the more you make a commitment to a different life, and that’s where you get so many artists. Britain has many stunning landscapes – also known for their ancient and pagan legacies -but it’s very rare to have such a succession of so many artists visiting and living in such a rural place. Not all are concerned with the land, but it is interesting to see how art is made outside of the cities.

It always seems there is a potential that will click there, but it never quite does, and maybe that is what saves it. It’s not really behind the times, but it is bohemian, so it offers a kind of alternative to modern lifestyle. You can have a damn good social life there – quite unusual in the UK countryside.

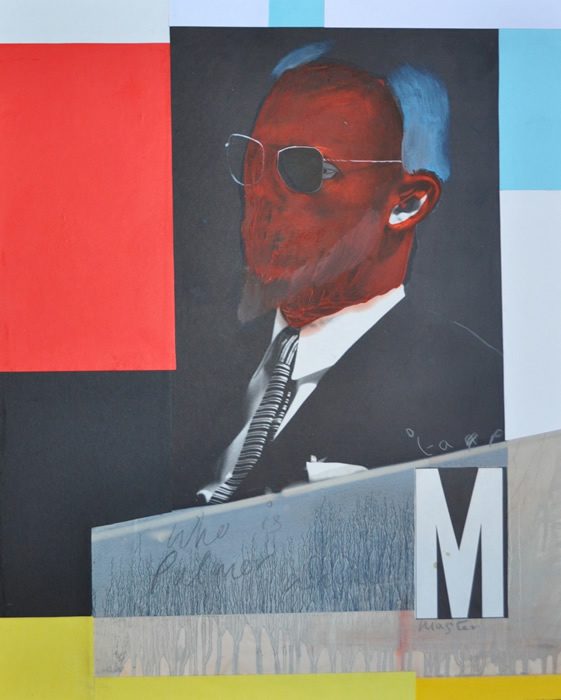

Who is Palmer White?

Palmer White’s work was a revelation to me. It was and is an example of something you could only get in Cornwall: a direct response to a raw and primal landscape.

After years of discussing ritual and ancient art with my artist friend, Paul Becker, we managed to track down Palmer’s work. We started to discover his subtle interactions in the landscape around Penzance. We thought of them as Revenants – as he seemed to be concerned with the death of the land. They often portrayed a malevolent force, and sometimes a protective guide. A face painted in mud on a mirror left in a tree at night, or tiny monk-like heads amongst mushrooms.

We were so excited, and devoted our time to searching caves and remote moors. He became a source of wonder. His work made us really study nature; it made us consider the obligations and purposes of his art and actions. So we started making performances, costumed dances in honour and in response to him. We built up quite an archive and decided to show it recently in Cornwall.

Palmer White exemplifies all that I love about so-called outsider artists. If he didn’t exist we would’ve had to invent him.

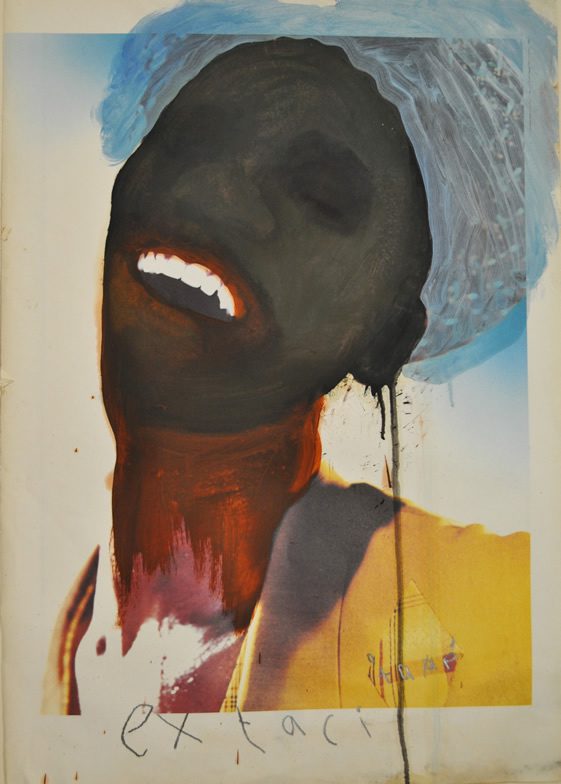

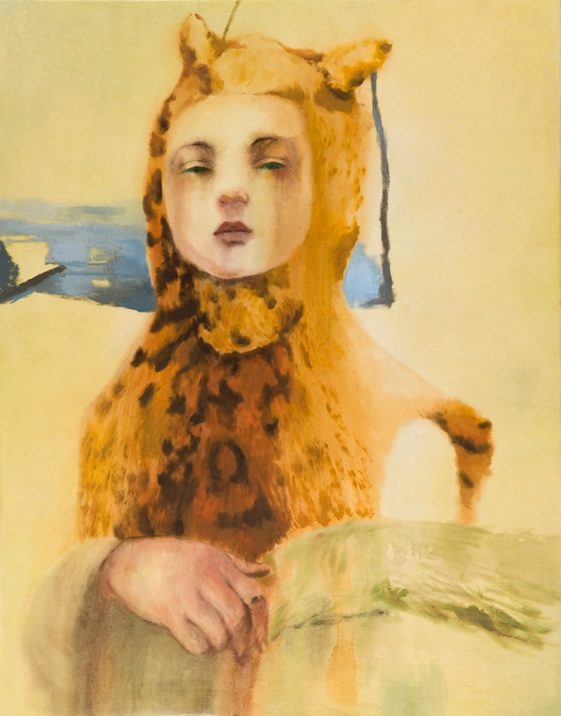

‘Idol’ Oil on Quartz based ground

As well as create, you curate. Some of your most recent shows include the hugely successful Revolver project, and ART75, and PRINT ! I know they took a lot of doing. Tell us a little bit about each, and why you got involved.

In 2007 – with another artist friend Volker Stox – we got access to an ex-car showroom on Penzance seafront and decided to stage a series of shows and events within 6 weeks called Revolver. Every Friday we had a big party to open a new show and we were able to show over 60 artists, graduate to established, local to international. Large scale and spontaneous works like video projections, installations and such like could be shown and documented. The emphasis was placed on having a really good time. It generated a lot of new work and friendships. We then published Revolver as a portrait of what was going on then.

The joy of Revolver seduced me into staging similar sprawling events. ART 75 was the anniversary of the art deco lido in Penzance. Together with Richard Ballinger, we asked 75 artists to use the 75 cubicles for installations, films, sculptures etc. We had performances, bands, synchronised swimming and workshops.

PRINT! I did last year with Bernard Irwin. Alongside the works of historical and renowned artists, we had a printmaking workshop – located at the heart of the space – and artists and the public made posters, books and prints throughout the 3 month show. By bringing such diverse people together to share ideas and skills it becomes so much more than a show.

Shows are incredible. The main obstacle is getting access and permission. Once you do, then the public and community unleash overwhelming generosity and energy. Society is so ordered now, and the art world is no different: art schools, galleries and art fairs tend to be quite dry, conformist and serious.

Revolver, motorbike by Hadrian Pigott

Taap, photo by Steve Tanner

Over the years you’ve collaborated with all sorts of people, including your own family. One of your most fruitful partnerships has been TAAP, a small group of similarly minded artists. How did TAAP begin, evolve, and what – if anything – is the group working on now?

I asked a group of artists to make the show Possessed Possessions after Xmas 2010, and work together in my studio. No one was making any money and the vast studio I had and loved had to go, so this became a swan song to it. Most of our lives were imploding in many ways and this provided a rich compost of ideas. We made sculptures, films, performances and fashion shows – and kept trying to humour and surprise each other. We held the evening Silver Screen Séance, which celebrated the extent of our joy and failures.

I really think it’s important to create landmark times in your life – when you can say that couldn’t happen again, but was wonderful. Collaborating is a great way to make great friendships. I also asked my kids to help on the Palmer White search and it was a remarkable way to spend time together. And we stole all their ideas.

Taap is a very different beast now, we are all nearly rejuvenated. Three of us meditate like we have just found painting, but that practice is about trying to move forward. We’ve just had a show of one off posters based on our love of the tradition. These started by de-facing drawings and paintings of mine – work I couldn’t bear to burn or exhibit. They drew all over them, tore them in half and we made up scenarios about the new characters that arose.

‘Revenant, Prussia Cove’ with Paul Becker

‘Leopard’ Oil & quartz on canvas

In the end, despite the collaborations, the sculpture and print work, you’re a painter. How does everything you do relate to painting? And what is it about painting that makes you so want to paint?

I ‘m hoping that all the projects I’ve done recently will feed into a different way of painting. I’ve made some good paintings, but I have always been frustrated by not being able to include all the stuff I’m interested in. I think now I will paint in a kind of collage way.

Looking at great paintings is like the thrill of painting itself: whilst you can be overwhelmed, it’s often very subtle; you may look at it for just a few moments, but it is enduring. You know, like childhood memories are usually incidental, like the wall at school or all the dog shit in the alley on the way to church with my nana. Painting is often about that stuff – as a vehicle for all other human experiences. The activity of painting is like meditating. You forget why you’re doing it.

Over the last few years I’ve been collating scrap books, with images from all sources. From these, I want to make my new paintings embracing all influences and experiences. I have many large paintings stored in Penzance. They vary in quality, and I can’t keep all of them, so I will be painting into them, collaging and may ask friends to add their mark. It will be like collaborating with my former self. I’m looking forward to our chats.

Jesse Leroy Smith now lives and works in Brighton – [email protected]. Both Smith and Taap are on Facebook.