Tony Garifalakis makes pictures that are invasive, muscling in on accepted meanings and discourses and turning our assumptions against us and against his subjects. From Vladimir Putin to Charles and Diana, his appropriations of images of the powerful and famous are both defacements and derangements: the threatening splashes of black in his series Mob Rule threaten not only the icons depicted but the viewer as well. In his series Affirmations, a range of anonymous figures from Middle America to the Middle East point guns directly at the camera and spout self-help truisms such as ‘I love and accept myself exactly as I am’ or ‘I am a beautiful being of light’. Violence extends in all directions, unpredictably, and leaves nothing untouched. (The pictures can also be very funny, you might be surprised to learn.)

His new exhibition opening tomorrow (and running till 4 July), Anti-Christs — presented by blackartprojects at Chalk Horse, Sydney — is seemingly an inevitable development in Garifalakis’ work: for this artist who is so interested in iconoclasm, what emblem could be more potent than the cross? Here it comes to function as the fulcrum of exactly the kind of aesthetic and moral shifts that Garifalakis is always tracing, turned upside-down and inverting the iconic photographs that it transverses. It becomes both the holder and the revealer of internal darknesses, corruption and threat, resulting in a show that’s strikingly unified yet develops in a number of different directions as it’s viewed.

In advance of its opening, I chatted to the artist about some of the thinking behind his work and practices…

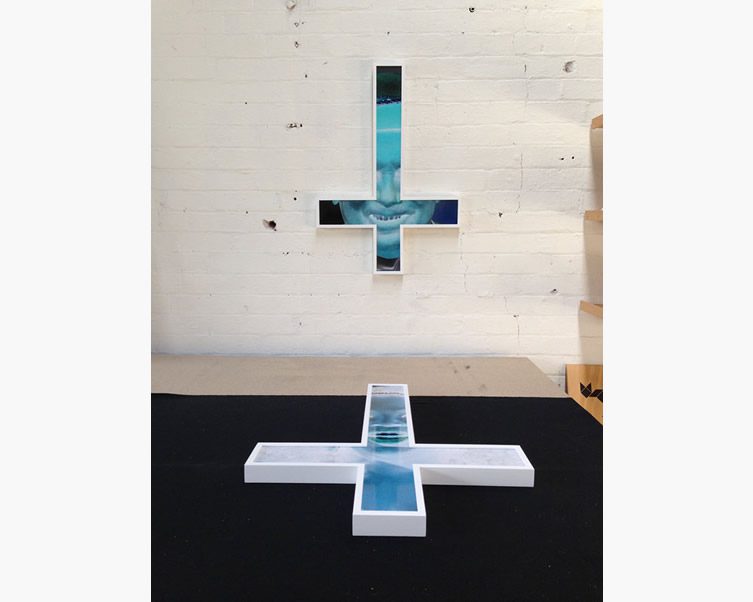

Tony Garifalakis,

Inverted Crucifixes, 2014

Installation view, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne

Photo, Christopher Day

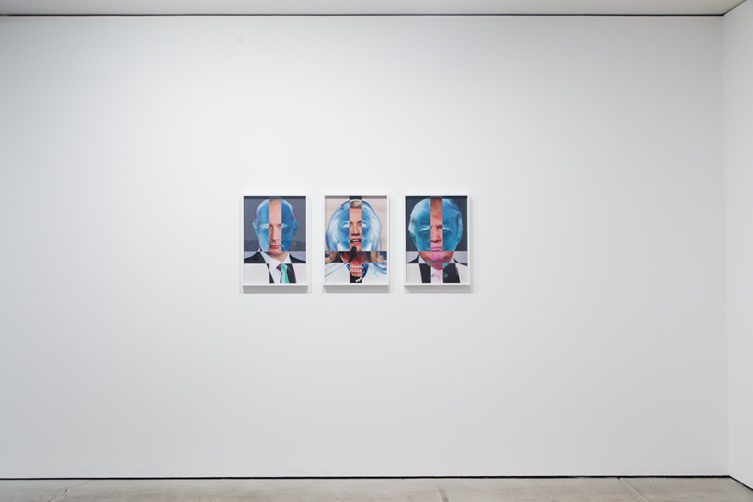

Tony Garifalakis,

Anti – Christs, 2014

Installation view, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne

Photo, Christopher Day

There is a strong undercurrent of violence in your work — often, in fact, it seems both thematically and aesthetically to be much more than an undercurrent. But there’s also humour. Where would you say you draw the line between the genuinely sinister and the satirical? Is there a line?

It’s more of a grey area than a line, and I think my most successful works inhabit that area between humour and gravity. It is never my intention to produce work that is considered either wholly ‘sinister’ or satirical; instead, I aim to create an uneasy tension in my work by utilising these and other elements.

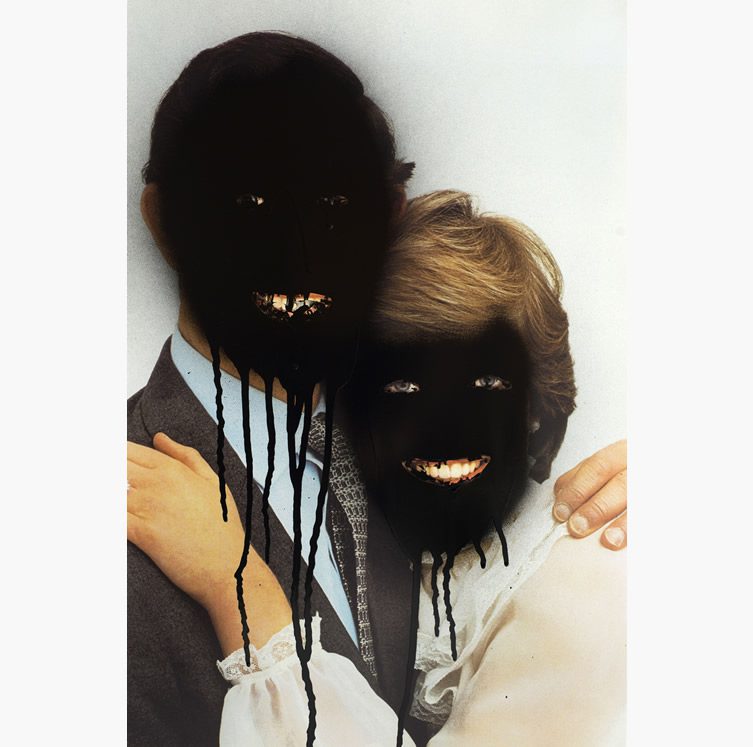

Tony Garifalakis, Mob Rule

Courtesy, the artist

Tony Garifalakis, Mob Rule [Installation] Courtesy, the artist

Your representations/adaptations/defacements of establishment figures could be seen to be doing violence both to the figures represented and to the viewer — for instance, in your Mob Rule series Charles and Diana look truly frightening yet also have been mutilated themselves. It’s unclear to me, in a really productive way, who is the victim and who the threat. Could you elaborate on that a little — or disagree completely?

It is precisely this ambiguity between oppressor and victim that I was aiming to achieve with these works. The series is made up of photographic portraits of heads of state, royalty and military commanders that I painted over with black aerosol paint, in so doing obscuring their identities.

The process used to make these works refers to and mimics the one employed by government agencies to censor sensitive material in declassified documents, i.e. the bold black line through sensitive information/text. By employing this textual process in a pictorial format and eradicating elements of the original image, its intended representation and ‘message’ are all but dispensed with, providing only an elusive trace of its source. This process of ʻcensorshipʼ works as a strategy for eliminating meaning and shifting the context of the visual information.

I chose the title Mob Rule because there is an ambiguity to the term that appeals to me. On the one hand, it implies government by the masses through democracy — the will of the people being achieved through the relatively civil process of voting. But it also implies the act of the masses attaining power through the criminal use of force, violence and intimidation.

Tony Garifalakis,

Anti-Christs #1, 2013 [Top]

Anti-Christs #2, 2013 [Middle]

Anti-Christs #3, 2013 [Bottom]

All: C Type print on Dibond aluminium

194 cm x 50 cm

Tony Garifalakis,

Inverted Crucifix # 3, 2014

C type print, oak frame

82 cm x 59 cm x 4 cm

Photo, Christopher Day

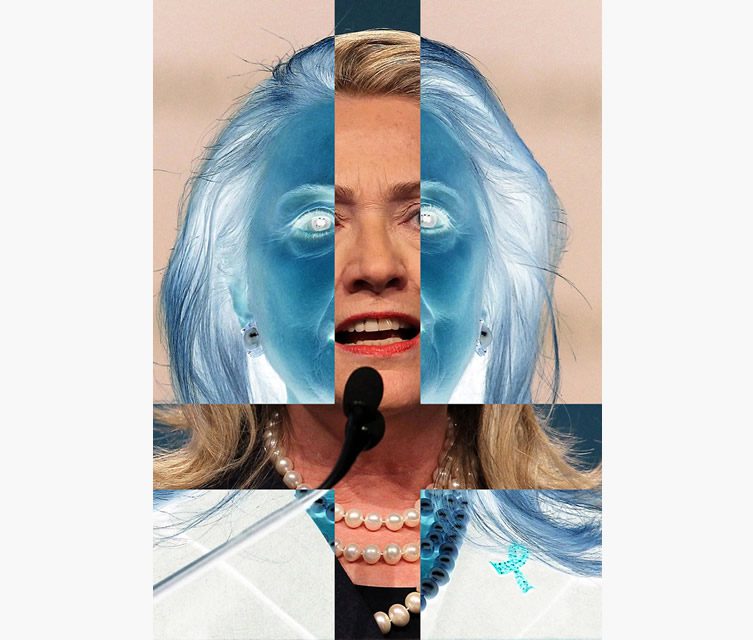

Anti-Christs seems to be strongly concerned with what can and can’t be seen, with the borders dictated by possibly THE most potent western cultural icon: the cross. To my mind, the works present the stark juxtaposition of the conventional representation and its sinister inversion, with the hinge between the two being the cross. Could you talk a little about that? It seems purposeful.

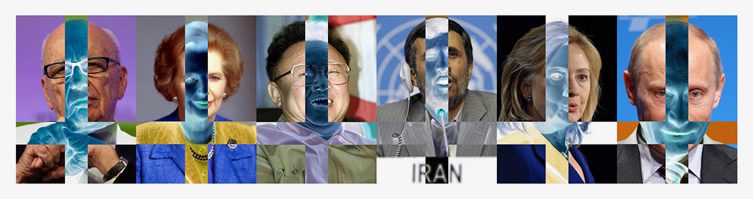

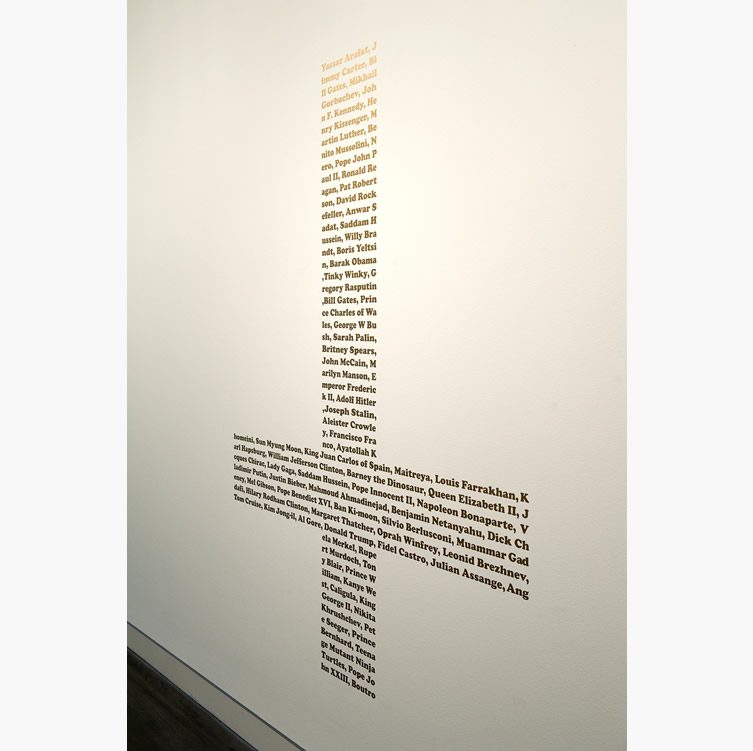

The Anti-Christs series is part of an ongoing project that examines the notion of the Anti-Christ and, more specifically, the attempts made to identify and name him/her. Over the course of several years I have compiled a list of public figures that have been considered to be the Anti-Christ. The information was mainly gathered from evangelical Christian and conspiracy theory sources. I was surprised by the vast collection of candidates that are, in most cases, sincerely believed to be the Anti-Christ. They included politicians; royalty; pontiffs; bankers; pop singers and, surprisingly, children’s TV characters.

The main body of Anti-Christs is a series of digitally manipulated found images. Each image is overlaid with the outline of an inverted crucifix and the area within the form of the crucifix is inverted to reveal its negative. This leaves us with a photographic image where both positive and negative areas are visible, the negative being in the shape of an inverted crucifix.

This is initially a simple visual strategy meant to represent the “Anti-Christs” but, as you have observed, it also serves to illustrate the simplistic notion of ‘good versus evil’, judgment and demonisation that exists in much political discourse, especially in regards to the media’s coverage of these events.

There are other works that belong to the series. Babylons are series of national flag designs that relate to the birthplace of the Anti-Christ.

Beasts is a text based wall work that brings together all the nominees for Anti-Christ and Damien is a series of wall drawings in the shape of inverted crucifixes that are made from the VHS tapes of the original Omen trilogy.

Tony Garifalakis, Babylons

Courtesy, the artist

Tony Garifalakis, Beasts

Courtesy, the artist

Your method has a strong component of appropriation and either recontextualising or outright effacement. With the new show coming up, could you talk a little about how you arrived at that method? Who were your main influences and who do you see as your peers?

I am interested in the way images are manufactured and the strategies used to construct meaning for their consumption in contemporary culture.

The types of images I prefer to work with are the ones that have been created for a utilitarian purpose and are designed to have a specific effect on their viewers (advertising, news, PR images, etc.). The appeal of working with these found images is to short circuit, or alter, their desired meanings and functions and open them up to alternative readings. I am not only interested in using found images, I tend to incorporate other ‘found’ elements in my practice as well. These include objects, sound and text.

Tony Garifalakis,

Branch of the Terrible Ones (detail of panel two), 2013

C Type prints

62 cm x 44 cm

Your subjects are global. To what extent do you see yourself as a particularly Australian artist? In what ways does Australian politics and culture inform your work?

I consider myself an Australian artist in the sense that I was born in Australia and I live and work there. I don’t think there is much in my practice that is uniquely Australian. As you have noted, the subjects I generally engage with are global.

What next? What are you currently working on, and will the next thing be a thematic/methodological departure or continue to move in the direction of your previous and current work?

I have recently been playing around with some ideas for three-dimensional works informed partly by public barriers and crowd control systems.

Tony Garifalakis’ Anti–Christs runs at Chalk Horse Gallery, Sydney, 18 June — 4 July and is presented by blackartprojects.

Tony Garifalakis’ Studio

Preparing for Anti-Christs at Chalk Horse, Sydney

Courtesy, the artist

Tony Garifalakis,

Branch of the Terrible Ones (Tryptich), 2013

C Type prints

Installation view, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne

Photo, Christopher Day

Tony Garifalakis,

Inverted Crucifix # 5, 2014

C type print, oak frame

82 cm x 59 cm x 4 cm

Photo, Christopher Day