A grad from RCA’s MA Photography, Felicity Hammond is a photographic landscape artist with some difference; her large-scale works are rich in complexity, yet a strong use of blue monotone (a process called cyanotype) encourages a more immersive viewing. Hammond’s subject matter is oft landscape, usually urban, and always telling of industrious change — the young artist’s fascination with the death of industry and the birth of technology is beguiling in its manifestation. Drawn to urban development like a moth to a flame, she takes up to a year photographing one site, only later assembling her composition.

Recently her work has focused on the development of London’s Olympic site. Watching the daily changes from ruin to glossy developments, Hammond’s work looks directly at loss, allegory and mourning in relation to landscape. Her particular vice — as we’ll find out later — is with construction sites, recycling centres and dug out holes, with cranes on standby. Well exhibited, Felicity won the RCA Metro Imaging Prize for Restore to Factory Settings, enabling her to develop her sizeable works on new surfaces.

We popped into Hammond’s North East London live/work studio to talk more about her deeply complex, strangely familiar pieces. We ask just how her compositions are created, and discover a life spent perusing architectural drawings and blueprints of the factories her father worked in, discovering what impact industrial evolution has had on her and society as a whole…

Felicity Hammond’s North East London Studio

Photo © We Heart

Felicity Hammond

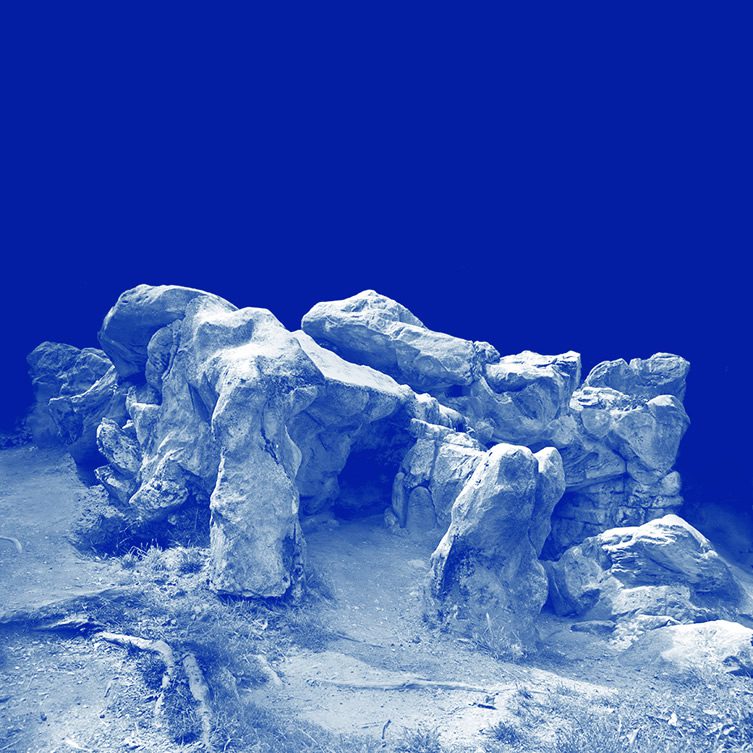

Restore to Factory Settings, 2014,

C-type print

Please tell us about your use of cyanotypes.

I did a residency at Bow Arts, and that was when I first started making cyanotypes. They’re a really early print processes of making photographs, where UV light is used to expose an image. I had a commission to work with the old Bow pottery factory, where the Olympic site is now, where they made Bow Porcelain that was blue and white. I then started thinking of blueprints and the planning of the area’s future, as well as the blue print of the pottery itself.

I was also looking at my father’s engineering manuals and drawings. So I guess this is where the blue came from, and where I took a lot of inspiration from – the decline of industry and the rise of technology: ‘restore to factory settings’.

Are you a full time artist?

I am definitely an artist first. I also trained as a teacher a few years ago, and lecture at Southampton University once a week. I also do a bit of museum and gallery education with the likes of the Whitechapel Gallery and Maritime Museum.

Structural ruin very much runs throughout your work. Why? Where did this passion come from?

When I first moved to London, just before the Olympics, I was watching the landscape completely change before me. I lived in Docklands, and could see the landscape being dug up and regurgitated. I’d get the DLR a lot, there you could see piles of dirt on both sides of the track – and I suppose I didn’t understand the process. You’d see all this debris but I couldn’t foresee the bigger, regenerative, picture.

One of the places that I took photographs of was in Canary Wharf, where they’d dug a massive hole in the ground but run out of funding. The hole was just left there, to fill with muddy water. It looked ruinous and ghostly, and I was hooked. Another reason for my structural ruin obsession was when I went to visit the factory where my dad had lived and worked, in Walthamstow. When I arrived it simply wasn’t there any more. There were no signs; it had completely gone, which was incredibly sad.

Felicity Hammond’s North East London Studio

Photography © We Heart

Can you tell us the process you go through when creating works such as Restore to Factory Settings?

I spend around a year photographing the same site and documenting its development over that time. There is a Baroque feel to the landscapes I choose, and they become shrouded with tarpaulin that looks incredibly sculptural – just like dressed objects in classical paintings. There’s theatre in these building sites, especially when they are lit at night.

You get the most incredible lighting off these shrouded bricks or timber; it really is incredible and very Baroque to me. I start to piece them together after about a year, and take inspiration from classical compositions, such as The Rape of the Sabine Women. I guess it’s like tapestry making, piecing together elements bit by tiny bit.

Can you also tell us about Monument to the Curiosity Zone, your tall neon sculpture…

I became really interested in the way that culture was being used in cities. The idea of a culture capital, and what that actually does to a city. I started with Stratford in the run up to the Olympics, and looked at what that did to the area, and how it impacted the local people. Looking to see if culture cures or contaminates an area – a paradox that I was really interested in.

That’s why the structure/column is in this ‘toxic’ neon colour. It’s a cheap material that reflects the glossy glass-fronted luxury apartments that have popped up in recent years. The filling is insulation, and represents the body of the piece. It is ruinous in its quality, and often discarded on building sites, which was fascinating to photograph. It is also very fleshy, and bodily, and made me think of the people within.

How do you decide whether to create a physical or photographic piece?

I suppose I was photographing the material, and I wanted it to go beyond a photo. I struggle with materials because I work with photography. I want to work with the physical but somehow, through the Perspex screen (of Monument to the Curiosity Zone), it has a glossy, photoesque surface. That takes away the tactile element, so even my sculptures have photographic finishes. Essentially the Perspex acts like a screen, and houses the content like a photograph shows the content. It’s a way of containing the mass… the subject.

Felicity Hammond

Of Margaret’s Wave – collaboration with Thomas Clatworthy, 2014

(This was made for a book published by Black Dog Publishing,

edited by Rut Blees Luxemburg, titled Science and Fiction)

Felicity Hammond

Restore to Factory Settings (folly 01), 2014,

C-type print

Felicity Hammond’s North East London Studio

Photo © We Heart

Your landscapes are fascinating and fictional. There’s so much to see and look at, yet they don’t look like they were plucked from your imagination. They’re very specific, and the collages strategically engineered. Would you agree?

Yes, I think so. I think painters would hate me for saying this, but my work is similar to painting. I am reappropriating classical pieces, so the work doesn’t just come out of my imagination. If I am gathering all these images and returning to these landscapes again and again, I’m engineering the outcome that becomes hyper-real. My work definitely comes from my memory, and the signs and symbols I create; a space for mourning, tragedy and more.

Your works are manipulated still lifes. Have you always worked with photography and collage?

My undergraduate was Fine Art Photography, so I took a real experimental approach to photography. I had Richard Billingham and Tony Clancy as my tutors so I was led in a very photographic way but always making sculptural forms and using them in my photographs. I was trained but always battling with the medium somehow. I never just photograph something for the sake of it. Photography is the material in my art.

Felicity Hammond’s North East London Studio

Photography © We Heart

What is it about the landscape, especially urban, that attracts you?

I’ve really struggled for some time to find out what it is that attracts me to it. I’ve only just started to realise. I love going to the tip, I love big recycling centres for the mass of stuff, and there is something about the unearthing of the ground, materials, that I’m really attracted to. It’s almost seductive in a way. I’m attracted to ruin. It’s that reminder of our temporality and loss that is really at the centre of my work.

There is a social and economical message in your work relating to urban spaces, cities, housing. In Restore to Factory Settings, you describe the local landscape as being ‘dismembered’. Is that not progress, development and providing people with homes? Or is it the private gains and ridiculous rents of property developers that you are having a go at?

I think my work is quite rich in multiple concepts, especially with the larger pieces. There are two strands really, the loss and the ruin and my personal relationship with the landscape, which is the reason I make the work. It does also talk about the social and economical landscape and it’s my frustration with having to find alternative accommodation (live/work studio) to live in my family’s hometown.

On a typical non-studio day, what would you be doing?

On a non-work day… oh dear… I haven’t had one of those in such a long time! How sad is that? My ideal day would probably be to actually sit down and do nothing. As boring as that sounds, I never get a chance to do that. Maybe read a book or go for a run?

***

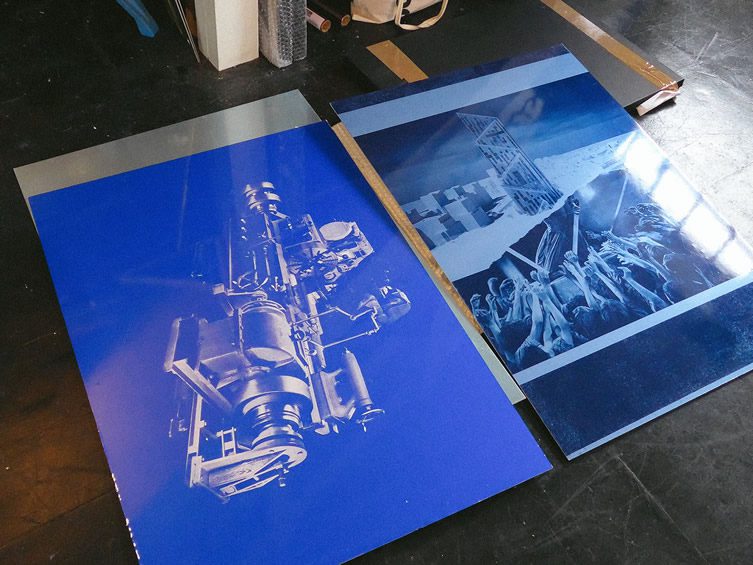

Felicity Hammond

Generating Change

Installation view from recent show: Restore to Factory Settings

at Vulpes Vulpes, Bermondsey.

(vacuum formed acrylic)

Felicity Hammond’s North East London Studio

Photo © We Heart