Temporal Cities is a project that speaks to our historic yet totally personal sense of the urban spaces in which our lives unfold. The title could just as well have been reversed to Urban Moments: it’s about places and times in equal measure, about what a city really is.

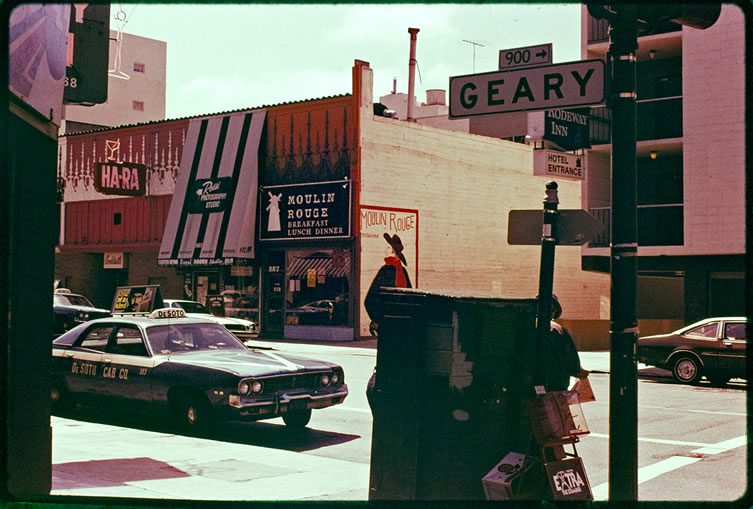

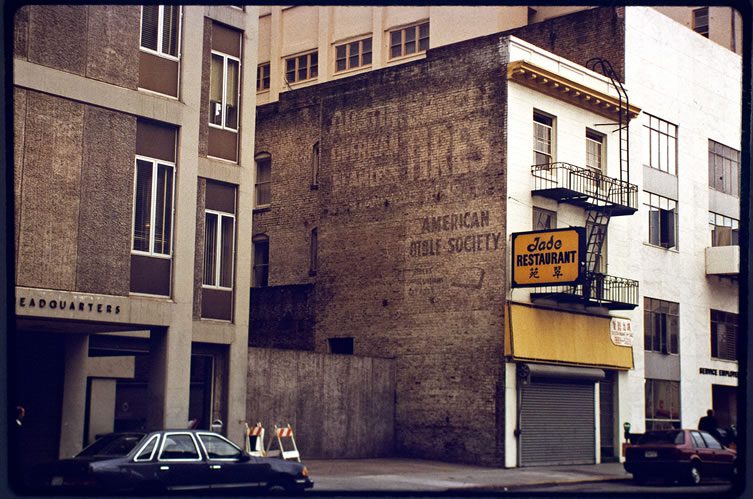

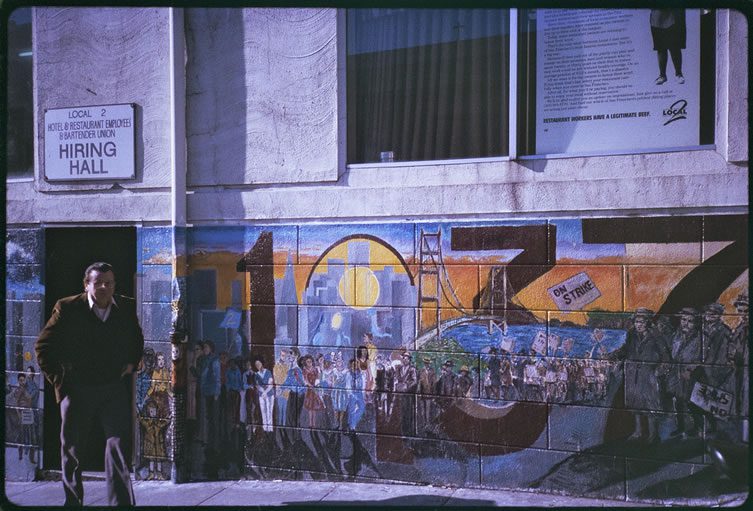

That it’s in San Francisco, California, seems appropriate. From world-famous landmarks to iconic architecture to colourful history to stunning scenery, from Bullitt to the Grateful Dead to the City Lights bookstore, it’s known the world over yet has retained its counterculture aura of quirk and idiosyncrasy. Of course, it also has its share of the usual controversies over 21st Century gentrification and the pricing-out of anyone who’s not a twenty-something tech flash-in-the-pan or finance wizard — but that depersonalisation, that loss of character and identity, is where Temporal Cities comes in.

It’s the brainchild — heartchild, let’s call it — of artists Lizzy Brooks and Radka Pulliam. Lizzy is a Stanford-trained historian who holds an MA in African Studies from London’s UCL-affiliated SOAS and an MFA in Photography and Electronic Media from the Maryland Institute College of Art; Radka is an interdisciplinary artist, working with everything from drawing, video, embroidery and interventions, who trained at California College of the Arts and has shown at a number of prestigious spaces. She received the Yozo Hamoguchi Fellowship in 2009.

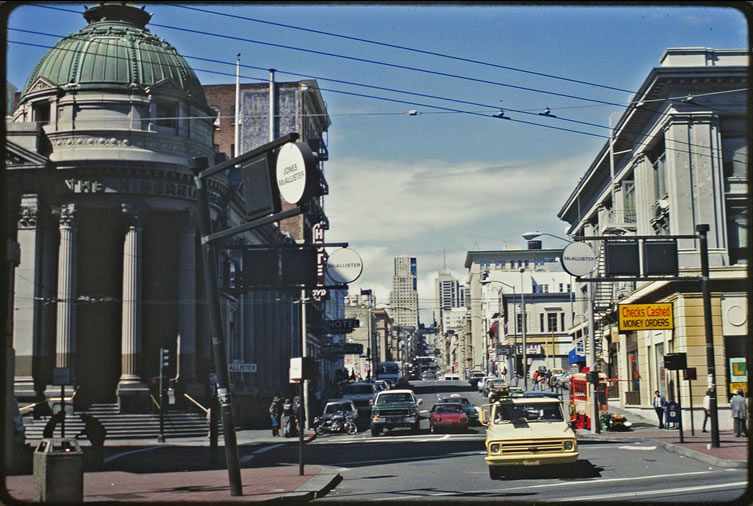

They both live in the Tenderloin; this quintessential synecdoche of San Francisco is in their blood, hearts and art. Temporal Cities is the kind of thing that could be undertaken anywhere, but isn’t — it’s here, in San Francisco, in the Tenderloin.

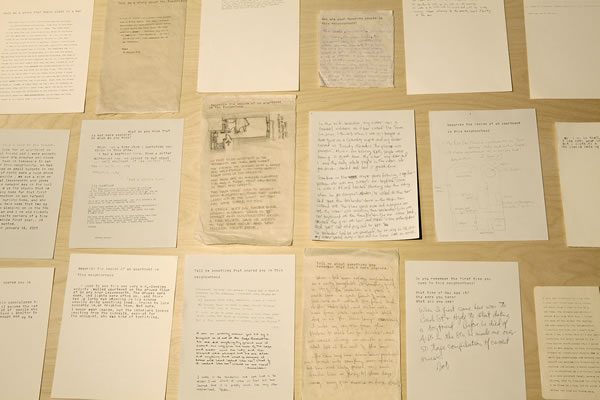

How it works: a slideshow of historic photographs is projected onto the window of the Tenderloin Museum, visible to passersby on the sidewalk at night. The people passing — they could be long-time locals, city-workers, new-ish arrivals, repeat visitors, anyone with a Tenderloin history — are drawn in, and once in they are given the opportunity to share their personal Tenderloin history, whether by microphone or typewriter. Thus, history is used to prompt more history, historical images making people understand their own memories and experiences as historical, and to add their lives to the record of the neighbourhood’s life.

Brooks and Pulliam want to engage their community in a way that specifically isn’t about all the predictable polarising debates about gentrification and change. Instead, they simply want to create a space — and record what happens in it — where ‘place and personhood’ can be reflected upon and talked about. ‘Our work,’ they say, ‘is to listen, to look inward and to observe, to share the shifting ground with our neighbours and to acknowledge one another.’ Important work.

But as the photographs that accompany this article show, Temporal Cities seems to be doing something even more fundamental: it’s become a place of hugs and broad grins, a reminder that though urban living is usually thought of as isolated and insular, in fact living at close quarters with thousands of other people can be a thing of joy. And if that’s not what neighbourhood is about I don’t know what is.