Award-winning photographic artist Roger Ballen has been taking pictures for five decades. Noted for his black and white ‘documentary fiction’ photography, Ballen’s ethereal aesthetic is rich in narrative—trancelike and intoxicating; transfixing in its oft-extreme nature. Roger Ballen challenges his viewers by questioning their understanding of what is real, frequently macabre, always visceral.

Roger Ballen by Marguerite Rossouw

Leaving his home in California to explore the world, Ballen’s life work began with a determination to hitchhike around the world in the 1970s. Drawn to what he calls its multi-dimensional nature, he settled in Johannesburg a decade later—where a passion for geology and photography would take hold.

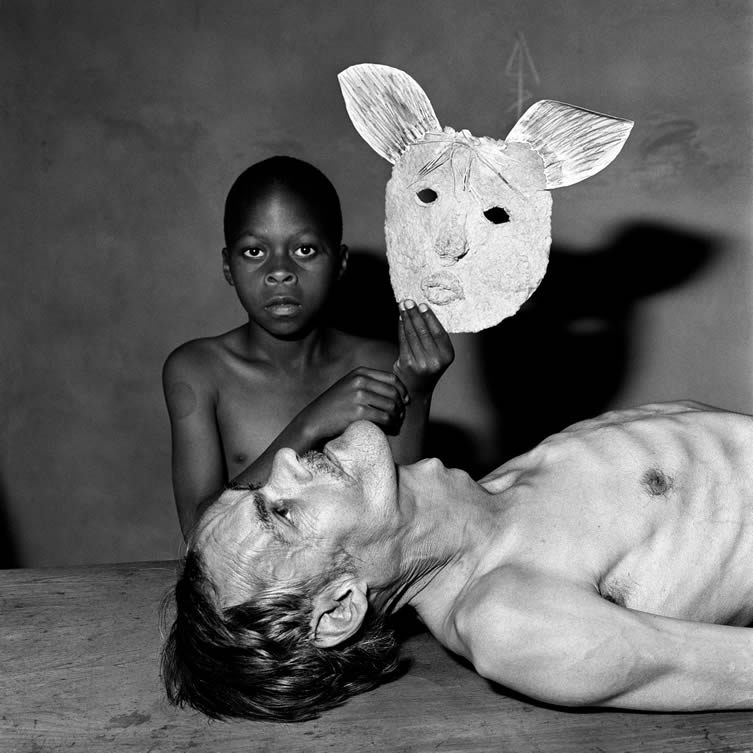

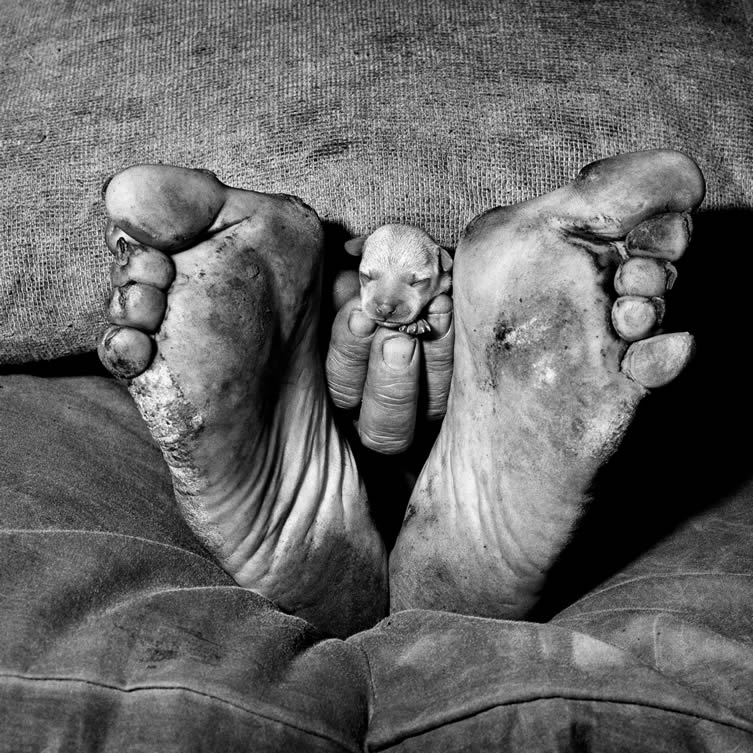

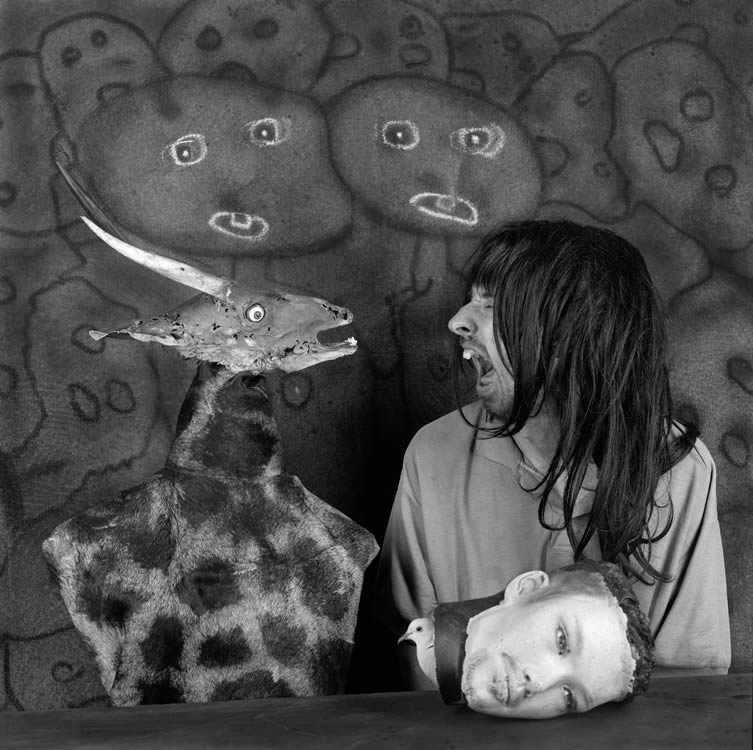

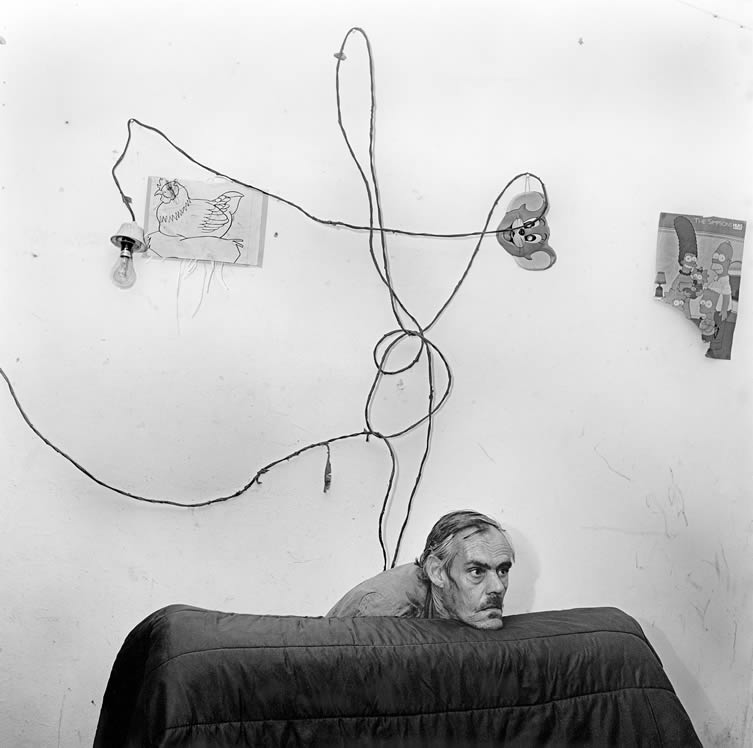

Combining photography with sculpture, drawing, and painting—depicting marginalised personalities, animals, broken objects, windowless sets, and old dilapidated rooms marked with primitive and archaic graffiti—Ballen’s work has slowly evolved over the decades; contorting into an inimitable style that straddles a thin line between reality and fantasy. Unmistakably real in their unpolished raw grit, the photographer’s subjects are set against tumultuous environments and scenarios that give way to the concept of reality—his personally curated worlds intrinsic to the style that has been dubbed Ballenesque.

In search of elucidation, We Heart spoke to Roger about his aesthetic, collaborations, and life in Johannesburg. Ballen reveals what an iconic photographer is made of; what comprises the perfect image; his connection to his subjects; and details on his latest collaboration with Ninja and Yo-Landi of the abrasive South African art-hop project, Die Antwoord—including a We Heart exclusive of his first colour photographs of the duo.

You photograph some interesting individuals—frequently outsiders—can you tell us how you choose your subjects?

An instinctive thing draws me to particular individuals. What’s important is the aesthetic that I apply to my photography and the way I transform people. So while my pictures may say one thing to one person, to someone else they may say something completely different. What you are looking at, through my history in photography is a transformative Roger Ballen aesthetic. My subjects don’t have to be outsiders or impoverished. I’m a psychological, existential photographer; not a person who is interested in making political or cultural statements.

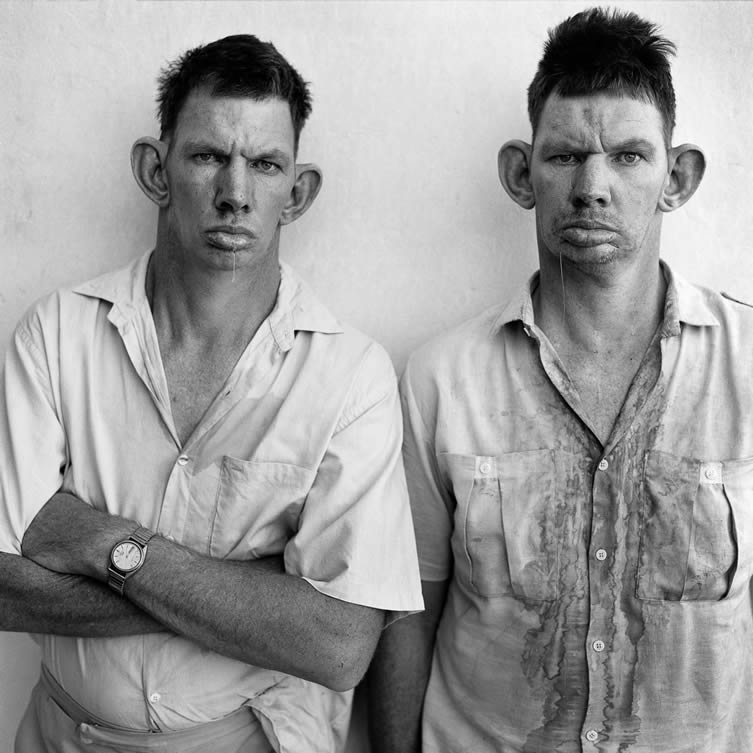

Dresie and Casie, Twins, W Tvl, 1993

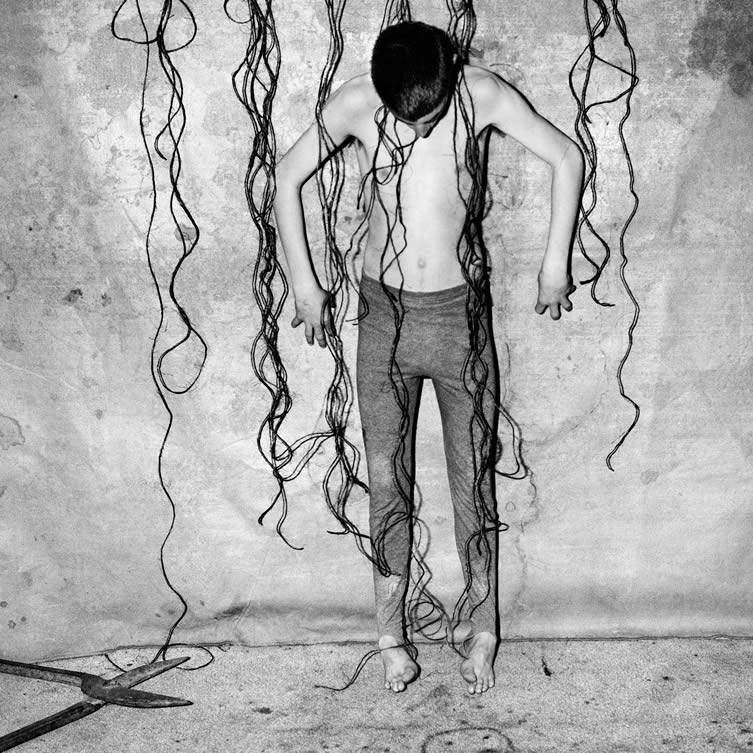

Cut Loose, 2005

You’ve lived in Johannesburg since the early 1980s, can you tell us about your emigration from the USA; why it happened, and what drew you to South Africa?

In 1973 I graduated from the University of California, Berkley. It was the hippy and counter-culture period, and I was anti-western and restless and felt like exploring the world. After my mother died, I told my father that I would be away for a few months, but it ended up being five years. During this time I made an overland trip from Cairo to Cape Town. In 1974 I hitchhiked across Africa, I found the country very interesting and met my future wife.

Dead Cat, 1970

I developed an affinity with the place as it was intimate and had multi-dimensions to it. Because I had lived through the civil rights era and travelled across the world, what was going on in South Africa wasn’t new to me, even though I was against Apartheid. I then left and made a trip from Istanbul to New Guinea, then eventually made my way back home to make my first book Boyhood in 1977. A year later, I started studying again and did a PhD in geology, which I finished in 1981. South Africa is a great place to practice geology, so I returned in 1982 and have been in Johannesburg ever since.

What makes a good photograph?

A good photograph transforms the subconscious mind. It stays with the person, it challenges them and expands their mind. It’s a deep psychological and memorable experience. To me, a good photograph is not something you see a million times. The amount of pictures produced has increased by the thousands every single day. A strong picture enters the subconscious within microseconds, but looking at them on your phone or screen doesn’t have the same impact. It’s a positive form of communication but not an art form. It does dilute the inherent value of photography as a whole.

Cover-up, Indonesia,1976

One Arm Goose, 2004

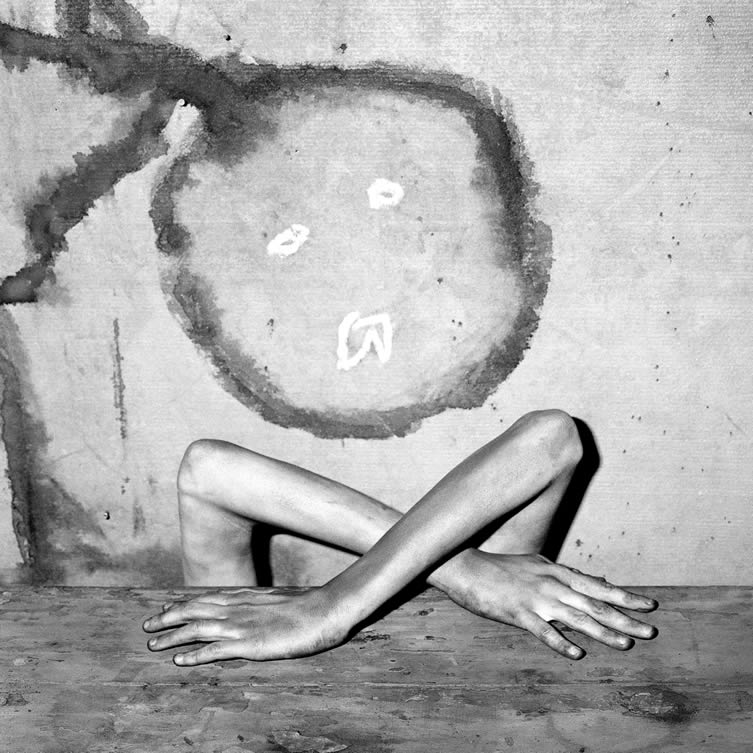

Five Hands, 2006

Why have you chose to shoot so extensively in black and white?

I have been shooting black and white film for nearly fifty years now. I believe I am part of the last generation that will grow up with this media. Black and white is a very minimalist art form and, unlike colour photography, does not pretend to mimic the world like the way the human eye might perceive. Black and white is essentially an abstract way to interpret and transform what one might refer to as reality.

What is the secret to being a good photographer?

I’ve known people for 20 or 30 years and have never taken a good picture of them, on the other hand, some of the most significant photographs I’ve taken within five minutes. A camera doesn’t have ears; you have to look at the visual aspect.

My pictures aren’t just about subjects, they are also about the drawings, the animals, the textures, and the optics—and there are thousands of things that make up a picture. If I find someone walking on the street, I’m 5% there. I’ve seen an interesting subject, but I’m not just going to put them in front of a white wall. What will make the picture iconic? This is where my imagination and experience comes in, and there are hundreds of things to consider.

Mimicry, 2005

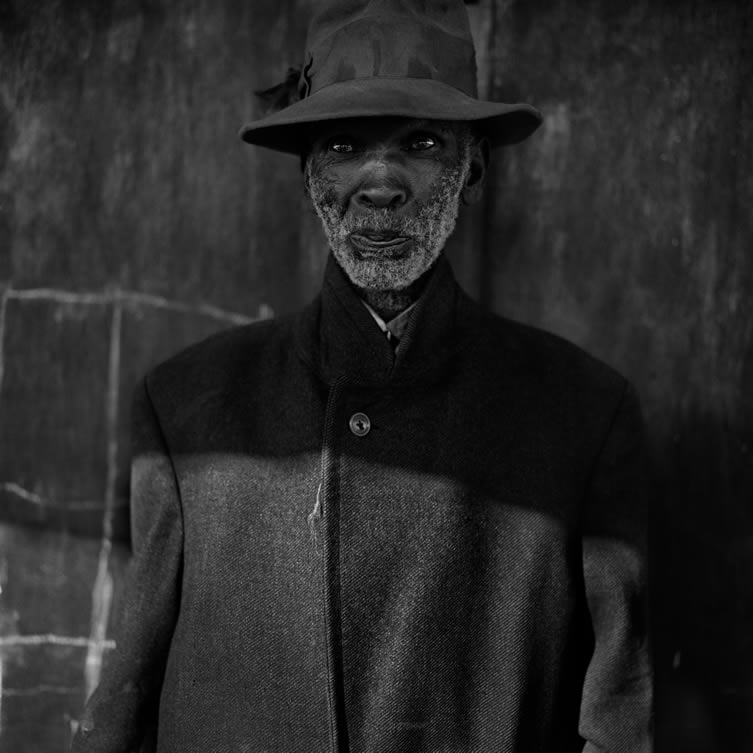

Old Man, Ottoshoop, 1983

Tommy, Samson and a Mask, 2000

You have described your work as ‘documentary fiction’, can you please elaborate on that?

When you look at my pictures, they are taken in so-called real places, whatever ‘real’ is. They are real places where real people live, but at the same time, the pictures are transformed using the Ballenesque aesthetic. What you see is an environment where you’re not quite sure of what’s what. That’s why my pictures have that enigmatic quality to them.

Stare, 2008

Tell us about your collaboration with Die Antwoord for the I Fink U Freeky music video and book. Creatively, how did the process go?

Ninja and Yo-Landi approached me in 2005 or 2006. At the time they said that they gave up everything for a year or so when they saw my work they reinvented themselves as Die Antwoord. We got talking and eventually started collaborating. The collaboration worked well because they have a deep understanding of what I do and respect it. We’re on the same wavelength so I did a lot of the art sets and they linked it to their music. It was a very harmonious process.

You’ve been working with them again recently …

I’m busy working on a new collaboration with them. For the first time in my long career, I have been taking colour photographs of them. Both Ninja and Yo-Landi were portrayed in different rooms dominated by my Ballenesque aesthetic, consisting of drawings, sculptures, and other objects. That’s all I can say for now.

Confrontation, 2018: The colour photographs of Die Antwoord were taken in January 2018 in a building in Johannesburg. Both Ninja and Yo-Landi were portrayed in different rooms dominated by the Ballenesque aesthetic, consisting of drawings, sculptures, and other objects. These images occurred at a time when Roger Ballen has begun shooting colour photography for the first time in his long career.

You have worked with director/filmmaker Ben Jay Crossman on a few projects now; is film now a part of your repertoire?

Ben and I worked together on the I Fink U Freeky video with Die Antwoord, also the films The Asylum of the Birds and Outland. I found him a very talented person, and he immediately empathised and understood what I was doing, so we became friends. Ben has moved to London now, and since working with him, I’ve made a whole bunch of other films: Theatre of the Mind, The Theatre of Apparition and Ballenesque. With every new project, I try to make a video because it is a parallel way of enlarging my aesthetic.

An exhaustive retrospective that unravels the world of Roger Ballen and his impactful body work over the course of four decades, Ballenesque—published by Thames & Hudson—is one of the artist’s most important projects to date. Over 300 photographs spanning 336 pages, and including an introduction by Robert JC Young, the book is a vital discourse on a singular career.

Puppy Between Feet, 1999

Sgt F de Bruin, Dep of Prisons Employees, OFS, 1992

Altercation, 2012

Head Below Wires, 1999

Man shaving on verandah, Western TVL, 1986

Devour, 2013

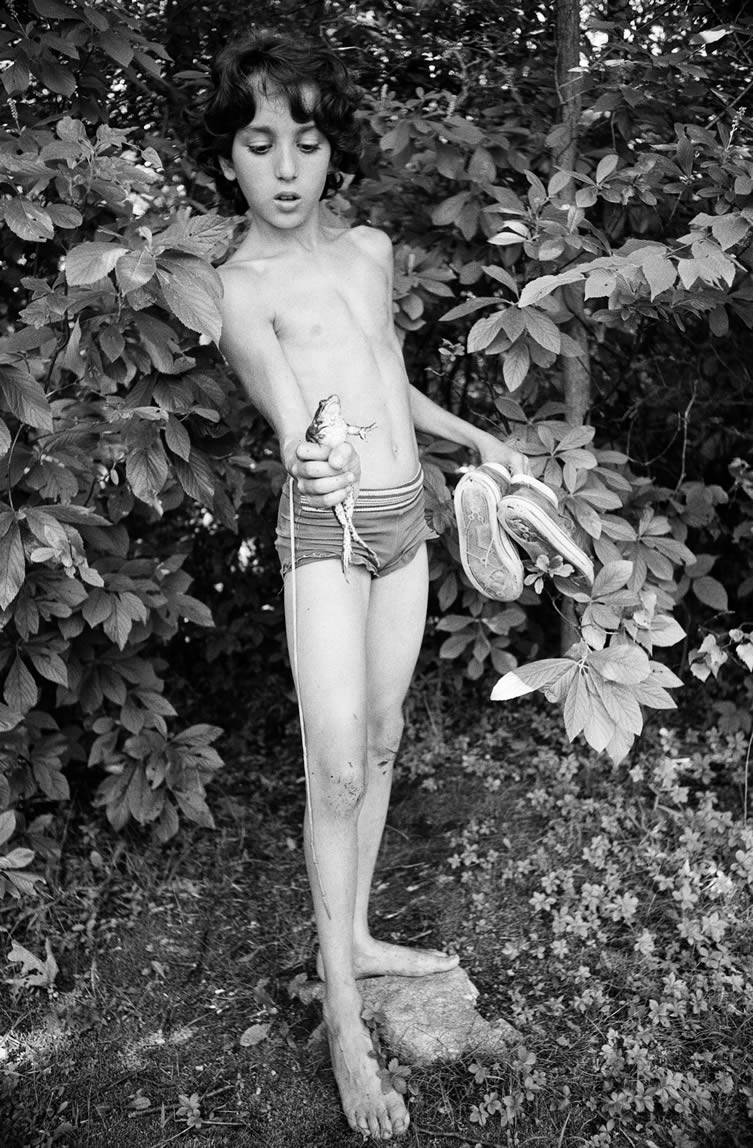

Froggy Boy , USA 1977

Face Off, 2010