The paragraph is an endangered species. Truth is, some Gen Z kids might never have got to meet these passages of text in their original form. Whilst the odd outlet is putting up a bold fight, certain publications cramming as many as three whole sentences into theirs, most online sources have cast the ancient syntax construct aside. Paragraphs have fought bravely, but it seems the sentence will win out; proudly sitting between one another with all that space to breathe.

If you hadn’t noticed.

The majority of online media outlets now put out their copy in painfully simplified, line-by-line blows.

It could be part of a global conspiracy to dumb us all down (like the one that saw the telly industry slowly turn brains into mush, one ‘one million per cent yes’ at a time), but the official line is: Google.

A report by digitalroo.co.uk has suggested that readability is a key determinant in a website’s SEO (search engine optimisation, for those of you lucky enough to not be saddled with this rubbish) ranking. To which extent plugins on websites like this encourage their owner to—along with other inanities—cast poor paragraphs on the trash pile. Nobody wants to get lost in a biblically-proportioned stream of consciousness, but there are aspects of online culture that grate badly.

Humanity hopes that this is one of the reasons why niche print publishing has enjoyed a joyous boom in fortunes. Why it’s not just precious designers who are enjoying the tactility of beautifully put together independent magazines. Exhibitions, symposiums, blogs … the new breed of print titles have gained a widespread following in creative communities and beyond. (MUNDIAL, initially launched as a one-off celebrating Brazil’s 2014 World Cup, has gone from shoestring to a staple in millionaire footballer’s wash-bags faster than Leo Messi’s feet can trick a world class defender.)

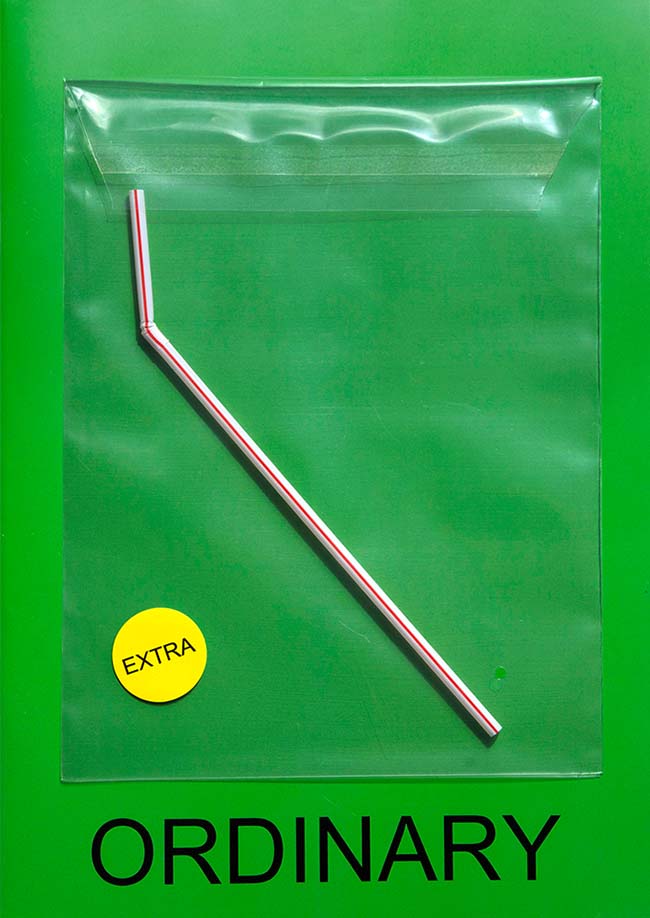

Ordinary, a quarterly fine art photography magazine featuring artists from around the world who have been sent one ordinary object to make it extra-ordinary.

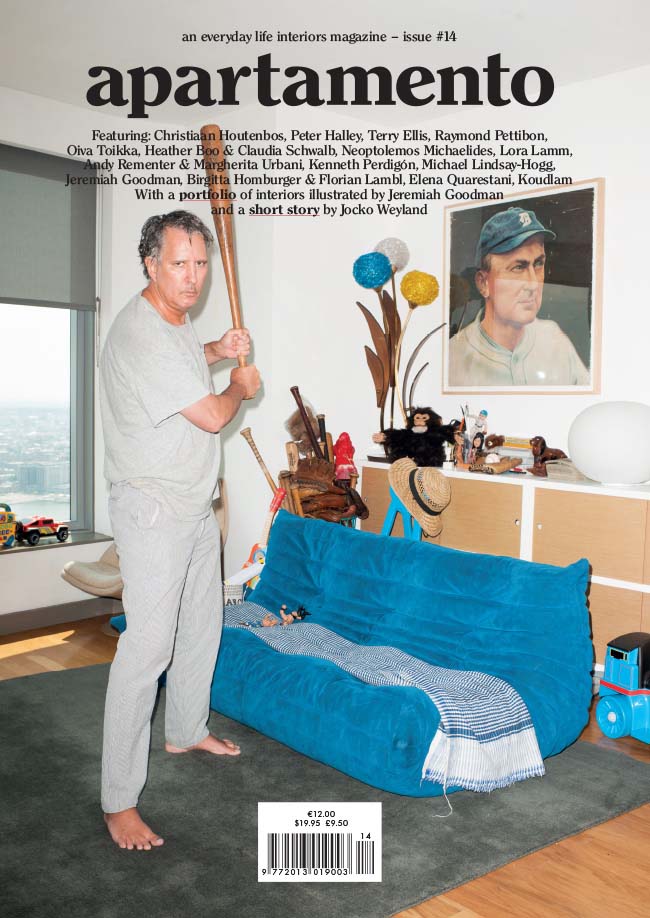

Apartamento, the much-loved interiors magazine that set the blueprint for the modern indie magazine scene.

Whilst the vanilla culture of Kinfolk or the perpetually-brilliant Apartamento have defined the new wave of print magazines, there are a host of titles prodding and poking at the medium’s boundaries; publications seeking to challenge the notion of what it means to be a magazine. Take Ordinary, a quarterly fine art photography magazine whose each issue focusses solely upon one ordinary object—mundanity brought to life by searingly talented creatives. Watch as creatives turn cotton buds or kitchen sponges into veritable works of art; the object itself attached to the front of each issue.

Then there’s Real Review, a magazine that bucks the trend of posh paper stocks and perfect-bound around-about-A4 pages. Long and thin, its extra folds give it the essence of a really high-brow version of those leaflets you’d pick up in Little Chef; content-wise it offers an inclusive take on architecture and our relationship with it. ‘What it means to live today’ runs the strapline of a truly unique publication.

Adopting an entirely new guise each issue, Buffalo Zine’s latest is a 432-page hardback book uniting food and fashion; its previous a kitschy ode to the Spanish seaside spanning four magazines of 116 pages each. A breathtakingly bold retake on the traditional fashion magazine, Buffalo Zine is a shining light for the freedom independent publishing allows.

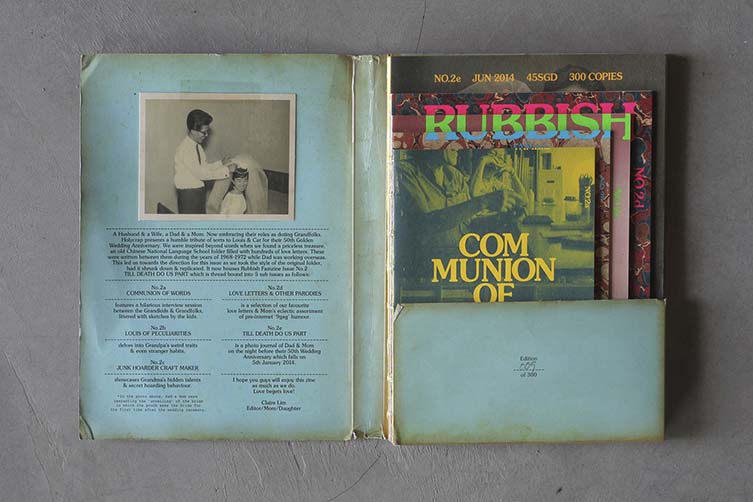

Taking that to the nth degree, Rubbish Famzine is an obsessively crafted, hand-made labour of love created by Holycrap—a Singapore art collective comprising mum, dad, and their two children (12 and 15). Their latest, A Return to Forever Eighties, features fold-outs, hand-applied stickers, and a 7-inch single featuring a song recorded by the family themselves. Previous issues have contained cassettes, twigs, a replica violin bridge, and pressed flowers.

Rubbish Famzine is the remarkable passion project of an art collective comprising mum, dad, and their two children.

As a rebuttal to one-sentence paragraphs, to clickbait and content written for algorithm over reader, the upsurge in interest for indie print publishing is a beautiful thing. But it’s also an important thing—as research flies into view about the negative effects of smartphone (ab)use. It has been found that teenagers spending five or more hours daily online were 71% more likely than those spending less than an hour to have at least one suicide risk factor (depression, contemplating suicide, making a plan, or attempting). The average person is scrolling upwards of 20 miles each year, and you can bet that somewhere, as you read these words, a smartphone-zombie will walk out in front of oncoming traffic. Apps are engineered to have addictive qualities built in. The attention economy is stripping a generation of its soul.

Of course it’s worse than that. Donald Trump is president of the United States as a direct result of shortened attention spans and technology capable of gross levels of mental manipulation. Vote Leave was found guilty of breaking electoral law during the Brexit campaign, with links to similar social media malpractice looming menacingly over the result. It’s about time we slowed down—and tech industry whistleblowers like former Google ‘design ethicist’ Tristan Harris agree; his Time Well Spent nonprofit a pioneer in outing the shady workings of the attention economy.

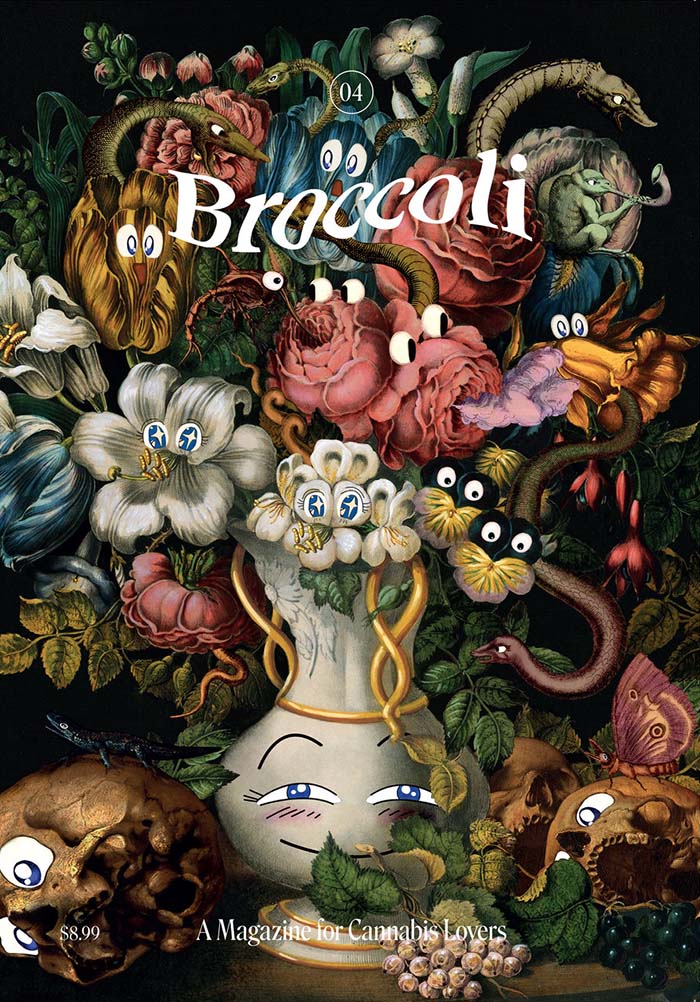

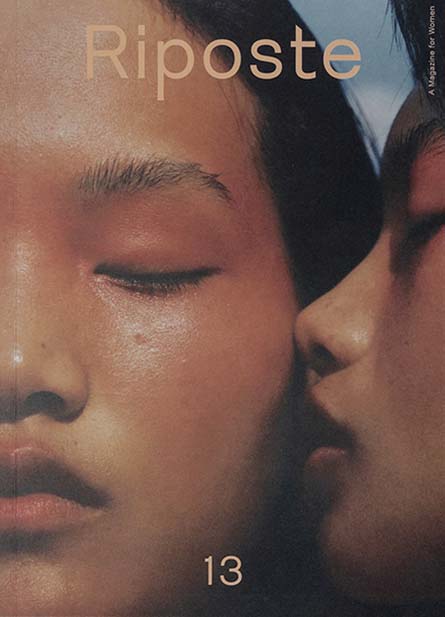

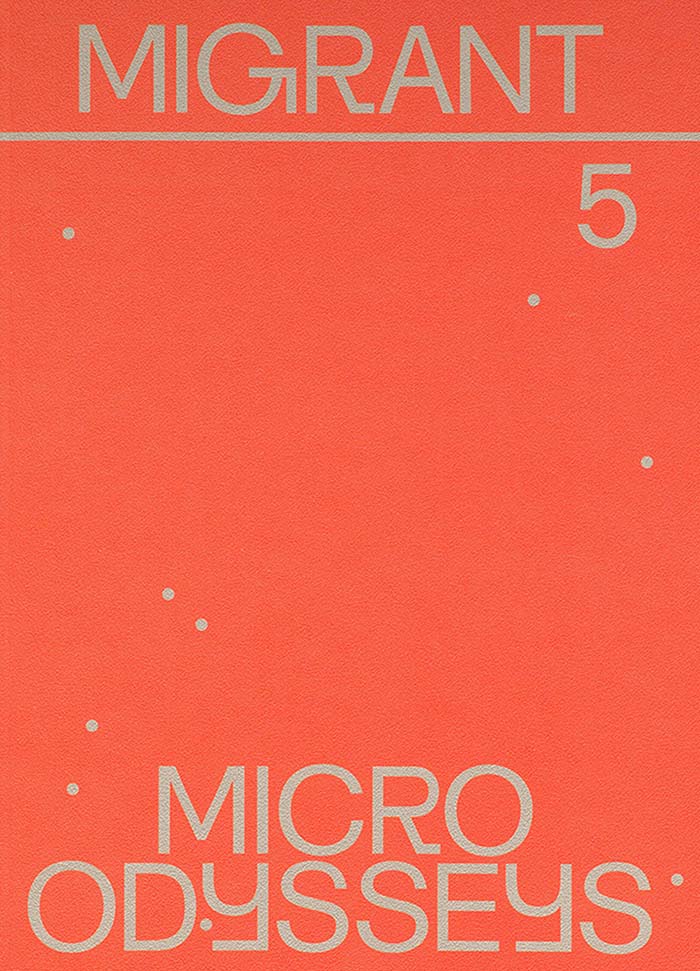

Broccoli magazine for cannabis lovers; Record magazine, a bi-annual publication that focusses on niche music communities; Riposte, ‘a smart magazine for women’; and Migrant Journal, exploring the circulation of people, goods, information, fauna, and flora around the world.

Slow is good. Slow might save our civilisation. Across the world, the slow movement—founded in the 1980s as a rebuttal to McDonald’s plans to open at Rome’s Piazza di Spagna—has found a new audience, with slow-travel, -media, -cities, -journalism, -fashion and so forth outlining worthy principles for mindful consumers. Independent print publishing is the perfect slow antidote to listicles and the Daily Mail’s sidebar of shame.

With niche publications covering everything from mental health to contemporary feminist witchcraft, tennis, hip-hop and (hopefully soon) craft beer, the indie magazine boom is now a literal phenomenon; anybody seeking to disconnect will quickly find a publication that speaks directly to them.

The means you’ll find Broccoli, ‘a magazine for cannabis lovers’ that applies a new forward-thinking perspective on weed culture in an age where perceptions on the plant are rapidly shifting; Record, a bi-annual publication that does for record collectors what Apartamento did for the interiors world; The Plant, a remarkable ode to botanical beauty; Riposte, an intelligent voice for empowered women; or Migrant Journal, a momentous piece of independent publishing that explores the circulation of people, goods, information, even fauna and flora, around the world—a critical view of how migration shapes society in a time of complex consequences.

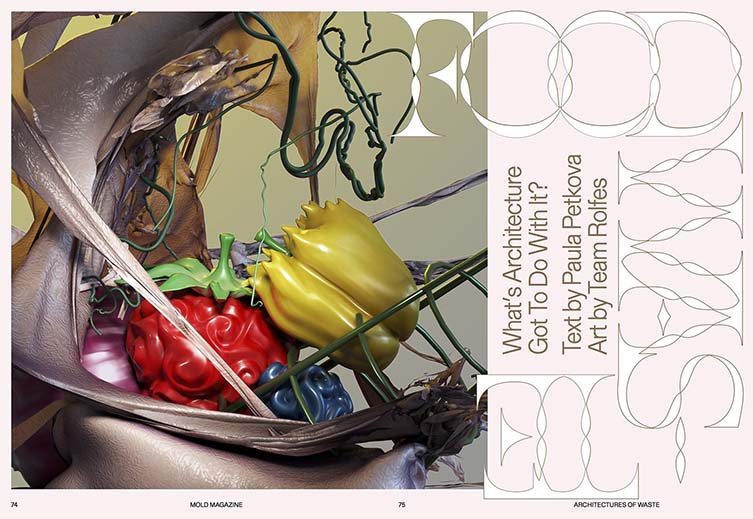

Similarly provoking political awareness, Good Trouble is a magazine dedicated to the culture of resistance, throwing the spotlight onto movements fighting for a better world, digging up stories where politics and protest intersect with arts and culture. Sharing some notions of activism, Mold is a bi-annual journal about the future of food; waste and the circular economy, edible insects, synthetic biology, and virtual reality some of the topics making their way into a vital discourse on how technology and design may help curb an imminent food crisis.

Mold, a bi-annual journal about the future of food.

Toying with typography, reimagining paragraphs and columns, using photography and illustration in ways web developers can only dream of, it’s not just defying clickbait or disconnecting from the digital loop that makes the indie magazine world so appealing, wily art directors and groundbreaking editors are using the medium to redefine notions of publishing—in an age where mainstream print is taking its final breaths, many rookie publishers are routinely selling out of issues typically priced well in excess of a tenner. Publishing as an art form. And some take that art form to conceptual levels.

Look at MacGuffin, a devastatingly handsome magazine that—like Ordinary—gives a platform to the seemingly mundane. Where the former delivers an aesthetic assessment of those objects, MacGuffin dives deep into the unexpected. Each issue based around a single object—the sink, rope, cabinets, windows—the magazine forms an immaculately researched compendium of information on the ‘Life of Things’; the wider cultural impact of these ubiquitous objects explored in immense detail. Similarly, Dirty Furniture offers a more design-focussed appraisal of an object per issue, ‘when design leaves the showroom’ the tagline for a magazine that explores our relationship with items of furniture such as the couch, toilet, and closet.

As the phenomenon rolls on, with it comes the freedom for new creatives to deliver publications with experimental concepts. Coming out of Beirut, a Dance Mag is a ray of hope for the fragile human race—uniting one another, transcending cultural differences via dance. A magazine to tell the stories of those “who are dancing their lives and giving their bodies a voice.” Sparsely designed, it relies heavily upon text, shifting the focus onto its writing; a brave move for what’s often seen as a post-text world, and another example of the importance of independent thinking in publishing.

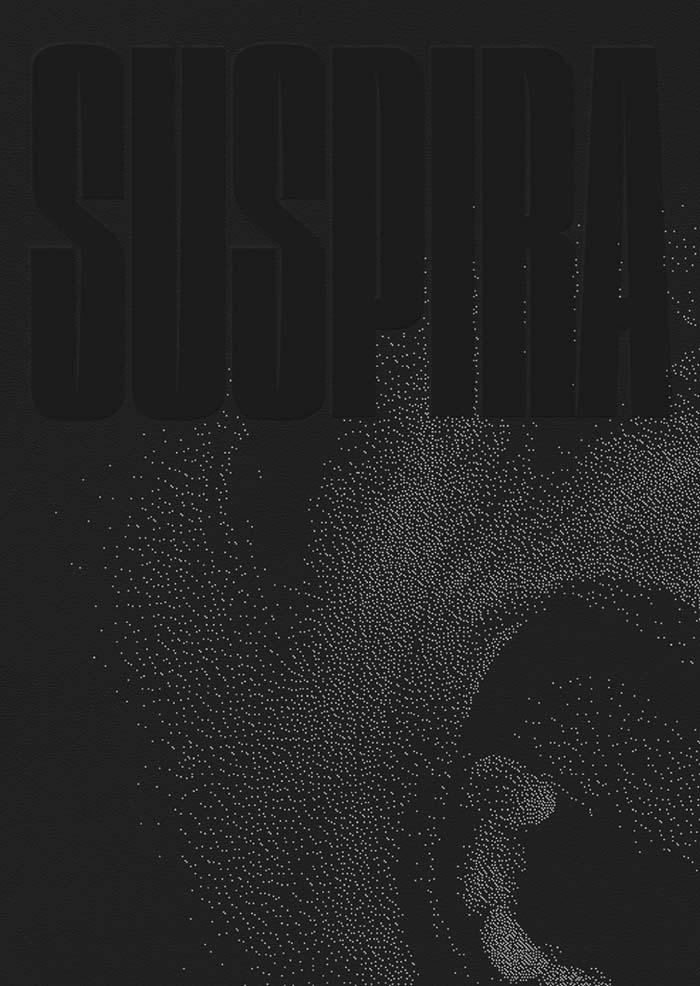

Suspira, a bold and brilliant horror publication that “dissects sinister subjects through a feminine lens.”

a Dance Mag tells the stories of those “who are dancing their lives and giving their bodies a voice.”

With a similar team behind it as the inspired contemporary witchcraft magazine, Sabat, Suspira is a deep dark dive into the macabre—a horror publication that “dissects sinister subjects through a feminine lens.” Unpacking contemporary issues through a filter of the bizarro, Suspira is an uncompromising read with equally discomforting photography and illustration. Unafraid to challenge, upset, or defy modern convention, the London-based magazine offers an unorthodox blueprint for subversive creatives in an age of vanilla. Publishing as an art form? Suspira is Tracey Emin scrawling ‘what are you so fucking afraid of’ across a canvas. And then some.

Liberating creatives and moving readers, the indie magazine boom delivers new perspectives on publishing. It is a movement that has absorbed the freedom of DIY punk zines and filtered it through the game-changing lens of titles like The Face or Dazed. Progressive and oft-polemic, these print publications give light to the darkest of culture’s recesses, offer bold new perspectives on familiar subjects, and give a voice to those ignored by the mainstream. Inspired and inventive, the indie publishing scene is increasingly impossible to ignore.

Stay tuned for our forthcoming dissections of the must-read mags across an array of genres.