One of my favourite London landmarks has to be Battersea Power Station. I have been lucky enough to get a look up-close and inside this incredible monument and to attend a lecture from the 20th Century Society about its history, so I thought I’d share what I’ve learnt.

Battersea Power Station was actually two individual power stations, in a single building. Battersea A Power Station was built 1927 -1933, and Battersea B Power Station, to its east, was added 1955-1957. The two stations were built to an identical design, providing the now infamous four-chimney layout.

Prior to the construction of Battersea Power Station, small power companies, created to service specific industries or factories, sold excess electricity to the public. Varying standards of voltage and frequency led to a decision by parliament in 1925 to standardise supply and bring it under public ownership. Plans for a small number of very large power stations, including the first one to be at Battersea, were born.

The Southbank site was chosen in 1927 because it was central to the area it would be supplying and close to the Thames – crucial for coal delivery and cooling water. Theo J. Halliday was employed as the architect with Halliday & Agate Co. as a sub-consultant.

There was immediate controversy – there were concerns that the power station would be too big (it’s still the largest brick building in Europe), that it would be an eyesore and that it would pollute London’s air, water, parks, buildings – and even the paintings in the Tate Gallery across the river.

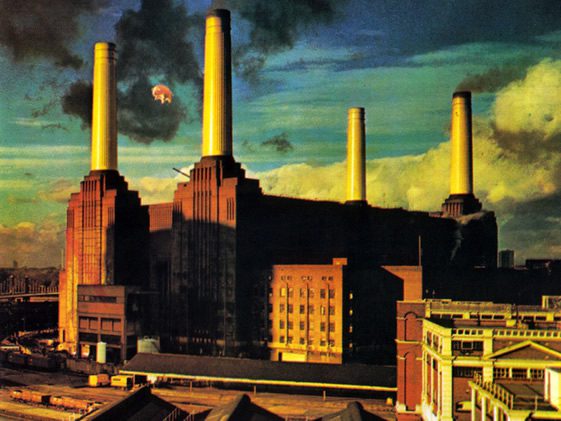

Photograph by Peter Dazeley

Eventually, in 1930, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, a well-regarded architect and the man behind the design of the trademark K2 telephone box, was brought in to style the building and appease the critics. Although Halliday was responsible for the initial exterior designs and the entire interior, Scott is usually credited as the architect. He in fact hated the towers – he proposed replacing them with square ones – and is said to be embarrassed by the praise now heaped upon him.

Nonetheless the resulting restrained jazz modern style of the ‘brick cathedral’ was immediate very popular. It was described as a “temple of power”; ranking equal with St Paul’s Cathedral as a London landmark. Its picture ran under the headline ‘Modern architecture for modern industry’ in the Listener in 1933 and a survey of celebrities voted it their second favourite building in the Architects Journal in 1939.

Photography © Marie Claire

However, despite efforts to reduce pollution, including devices fitted to the chimneys to ‘wash out’ sulphur and reduce airborne pollution that ended up creating worse water pollution in the Thames, inevitably concerns continued. In 1975 Station A was closed, followed by Station B eight years later.

Following a failed attempt to get the building listed between the closure of the two stations in the late 1970s, it is now Grade II listed and included in English Heritage’s Buildings at Risk Register.

Some argue its iconic status was sealed by its appearance with Pink Floyd’s inflatable pig floating above it, on the cover of their 1977 album, Animals. But it also appeared in cover art for The Who’s Quadrophenia (1973), Hawkwin’s Quark, Strangeness and Charm (1977), London Elecktricity’s Power Ballads (2005) and in films; The Beatles’ Help (1965), Michael Radford’s Ninteen Eighty-Four (1984), Children of Men (2006) and The Dark Knight (2008).

The A Station and particularly its control room are popular as film and TV sets because of their opulent Art Deco features. Italian marble was used in the turbine hall, and polished parquet floors and wrought-iron staircases used throughout. (Due to budget cuts after the Second World War, the interior of the B Station didn’t get quite the same treatment, and fittings here were from stainless steel.)

Sadly despite many proposals for regeneration from flats to theme parks, it seems to be more profitable to do nothing to the site – to simply to wait for its value to increase and then re-sell. Its size and condition makes it a difficult project for private regeneration – a public project as per the Tate Modern, or an organic development such as Dean Clough Mills in Halifax may be its only hope.